𝘿𝙚𝙢𝙤𝙣𝙞𝙯𝙖𝙩𝙞𝙤𝙣 𝙤𝙛 𝙃𝙞𝙣𝙙𝙪𝙨 𝙞𝙣 𝘽𝙤𝙡𝙡𝙮𝙬𝙤𝙤𝙙

Growing up in Ranchi, Jharkhand, Bollywood wasn’t just entertainment—it was a family ritual. We’d huddle around our old TV during festivals like Durga Puja, watching reruns of Amitabh Bachchan films at local halls like the Ranchi Auditorium. As a kid, I cheered for the heroes, but never questioned why the villains often looked like the pandits from our neighborhood temples, complete with tilaks and rudraksha malas. It wasn’t until I revisited those movies as an adult, during quiet evenings in my Ranchi home, that the pattern hit me. Living in a place where Hindu traditions blend with tribal customs—think Santhali dances mixed with Vedic chants—it felt jarring to see our symbols of devotion twisted into signs of deceit. This realization sparked my deep dive, not just as a cinephile, but as someone rooted in Jharkhand’s diverse cultural fabric, wondering how these portrayals shape perceptions in smaller cities like mine.

I’ll admit it up front: I never used to notice these details until I really looked. Growing up on Bollywood action dramas and masala flicks, I just assumed a scar or a wild stare made a man evil. But over the years I began to notice a pattern. Whenever the villain character wore a red tilak or carried Hindu religious symbols – a shikha (the tuft of hair on a man’s head), a rudraksha mala or a sacred pendant – he was almost always the bad guy. The good hero would be secular or Muslim, the bad guy would be a devout-seeming Hindu. In other words, Hindu identity markers became shorthand for villainy. I started watching those movies again with fresh eyes and reading what others had noticed. The results were striking: decade after decade of Hindi films have visually coded “evil” with Hindu imagery, flipping centuries-old symbols of faith and virtue into signals of menace.

What really bothered me was thinking about what that might mean off-screen. These movies are the stories we grow up with. If generations of viewers see “almost every villain has a tilak, shikha or rosary” while heroes are secular or Muslim, it can create a subconscious bias. Could it be that our entertainment is teaching us, without us realizing, to associate Hindu symbols with cruelty or fanaticism? That’s a scary thought for someone who loves both cinema and the rich heritage of our culture. I set out to understand how this pattern arose and what people – filmmakers, critics, and scholars – have said about it. The more I researched, the more examples I found: from the black-and-white classics of the 1950s to today’s OTT thrillers, it keeps coming up.

In this long-form blog, I want to walk through those examples and reflect on the larger picture. We’ll travel through Bollywood history, highlighting villains marked by tilaks, shikhas and sacred lockets, and discuss what they traditionally mean in Hindu culture. We’ll look at interviews and statements from directors and writers, and even some academic commentary on Bollywood stereotypes. I’ll admit, I’m writing from a concerned viewer’s perspective – a Bollywood fan and a Hindu who wants our symbols treated with respect. But I’ll back up my points with real film moments and even citations of what others have written. By the end, I hope any reader – cinephile or layperson – will see how even small costume choices in movies can shape big ideas about a culture.

Why a Tilak or Shikha Matters

Before diving into movie examples, let’s clarify what these symbols mean traditionally in Hinduism. Tilak (also spelled “tilaka”) is the vertical mark, often red, we see on many Hindu foreheads. Far from being evil, it is supposed to be auspicious. It’s often applied at home or temple prayers to honor the gods. According to Hindu tradition, a tilak on the forehead symbolizes devotion, purity and spiritual awakening. In other words, it’s supposed to remind the wearer (and onlookers) of higher values, of Dharma (righteous living). For example, one source puts it plainly: “In Hinduism, Tilaka on the forehead is a traditional mark symbolizing spiritual significance and cultural identity, often representing devotion, purity, or auspiciousness in various practices and rituals.”. Similarly, a shikha – the small tuft of hair left at the top of the head by some Hindu men (especially priests and Brahmins) – is meant to show spiritual commitment and identity. Hindu tradition sees it as a “cultural and religious” sign of being linked to Vedic learning and sacred duties. It literally marks someone as taking on religious duties (like a priest or scholar). A brief online glossary explains: “In Hinduism, Shikha represents a tuft of hair symbolizing spiritual commitment and identity, significant for practitioners, sannyasis (renunciates), and Vedic scholars”.

Another common marker is wearing a sacred thread or necklace. For instance, a janeyu (the shrived one’s cord for upper-caste men) or a rudraksha mala (a string of holy beads) signals religious discipline. A locket or pendant might depict a god or mantra. Traditionally these mean piety – the opposite of evil. So it’s startling when every time you see a villain on screen sporting those signs, the context suggests hypocrisy or malice.

In fact, Bollywood itself has often been aware of the disconnect. Take Gabbar Singh from Sholay (1975), maybe cinema’s most famous villain. Director Ramesh Sippy deliberately avoided giving Gabbar any of the usual religious trappings. He explained that for an action film villain, Bollywood had grown too fond of certain “tropes”: “dacoits wearing dhotis and pagris and sporting a tika” (tilak) and invoking religious imagery. Sippy broke that mold by dressing Gabbar in army fatigues with no tilak at all, making him iconic as the “pure evil” outlaw rather than a stereotyped rustic priest-figure. Sippy’s comment itself reveals how commonplace it had become to label a villain with a tika. So even in the 1970s, filmmakers were reacting to that pattern – a sign it was already entrenched.

Why might this have happened? One theory is that, under the guise of “secular” storytelling, Hindi films created a narrative where devout Hindus looked suspicious. Several observers note that film after film, a devout Hindu character is a baddie, while a secular or Muslim hero is righteous. In recent years commentators have been blunt. One Hindi newspaper critic noted how “the Hindu villain wears a striking tilak. The Muslim sidekick sports a white skull cap.” In other words, the main villain had the holy mark, while his loyal sidekick – who joined his crimes – was simply a secular Muslim man. This remark about Marjaavaan (2019) was not accidental – it was highlighting a broad trend. Similarly, much of the Hindu community feels these portrayals “systematically show Hindu symbols in a bad light.” As one activist put it, “the world of [some Bollywood films] is ignorant of the word subtle. The Hindu villain wears a tilak… while the Muslim sidekick sports a white skull cap.”

Meanwhile, filmmakers themselves have occasionally noticed. Pranay Reddy Vanga, producer of the film Animal (2023), faced a backlash for his villain but shot back, “For decades, Hindi films have shown a Tilak-wearing Hindu character as the villain. Those villains in the movies sport a ‘bottu’ (tilak) on their forehead,” he said in an interview. (Vanga was criticizing others saying his villain was bad because he’s Muslim – his point was: Hollywood did the same to Hindus first!) His blunt words echo what many have observed: that numerous Bollywood baddies wore tilaks, and no one batted an eye.

To summarize this setting: Hindu religious symbols mean virtue in culture, but in movies they get co-opted as visual shorthand for vice. The result is a cumulative suggestion that if your forehead is marked or your neck bears sacred beads, beware – you might be the “evil one”. It’s a form of cultural stereotyping, subtle but pervasive. In the rest of this blog we’ll unpack how this came to be, look at clear film examples, and think about the impact.

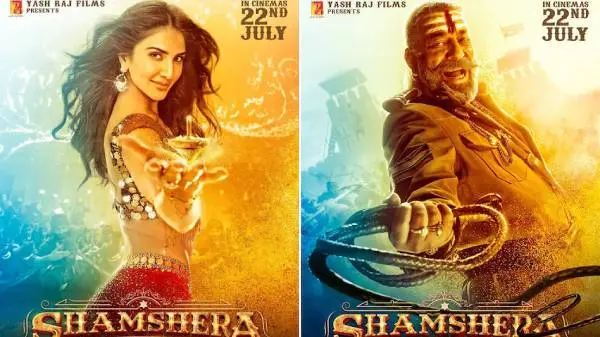

Above: A poster for Shamshera (2022), showing villain Sanjay Dutt with a Tripund Tilak (three horizontal lines) and a shikha. Shamshera drew controversy when critics pointed out that Sanjay Dutt’s character – a corrupt police officer – is visually marked by Hindu symbols while the sympathetic hero is more secular.

Villains of Old Bollywood: Early Patterns

To see how these symbols became villainous, let’s go back to classic Hindi cinema. In the black-&-white 1950s and ’60s, Indian films were still finding a visual language for hero and villain. Early movies often drew on mythology and folklore – the hero was noble like Ram or Krishna, the villain was demonic. But even there we see hints: often “bad” characters were shown with darker looks or outlandish style, while “good” ones were pure and simple. The association with Hindu symbols started to crystallize in the 1960s and ’70s.

For instance, Prem Chopra and Pran, some of Bollywood’s archetypal baddies of the 1960s–’70s, often played lecherous money-lenders or cold-hearted aristocrats. They sometimes sported a big red tilak on their foreheads, or a shawl and rudraksha beads. These were upper-caste, Hindu roles – yet their acts were sinful. Even if the script didn’t explicitly vilify Hinduism, the image was there. (Film historians note that in many movies of that era, the hero was secular or even Muslim, while the “bad maulvi” or “bad pandit” would do evil.) We don’t have a handy quote to cite for every single film, but the pattern was remarked on even by filmmakers like Sippy. He acknowledged that before Sholay, producers expected their villains to fit a certain look – often religiously coded – and making Gabbar a secular thug was a big break with tradition.

In the 1970s, two especially influential films exemplify this new style:

- Zanjeer (1973). This Amitabh Bachchan classic introduced what became the angry young man era. The villain, Teja (played by Ajit), was a suave gangster who definitely wore a prominent tilak. If you pause Zanjeer, you can see the red mark on his forehead when he’s on screen. He’s wealthy and smarmy, playing at religion (he likes to finger the necklace of “Maa Kaila Devi”, a Hindu goddess, in one scene). To me, that’s an early clear example: a Hindu thug literally using religion as his bling, and a secular-minded hero (Amitabh) fighting him off.

- Sholay (1975) – as mentioned, intentionally subverted the trope. Gabbar Singh had no tilak or mala. In fact, Ramesh Sippy said outright he avoided the “typical trope” of giving a dacoit a tika. That comment confirms that in the industry’s mind, villains usually had those symbols. By making Gabbar look modern instead, Sholay stood out – and yet the association was so strong that it was noteworthy to drop it. Even today, many fans are shocked to rewatch Sholay and realize Gabbar was never wearing saffron – it was a deliberate choice to make him memorable.

By the late 1970s and ’80s, this pattern had solidified. Masala blockbusters from Muqaddar Ka Sikandar to Ram Lakhan to Hukumat regularly featured villains who were not just criminals but often wealthy or powerful, with red or orange “tilaks”, long janeu threads on their chest, rosary beads, and even hidden temples and statues in their lairs. In contrast, heroes were almost always secular or modern (often poor or from lower castes). Tridev (1989) famously had corrupt high-caste ministers as villains – Dan Dhanoa plays a mafia don who regularly offers flowers and prayers at a home shrine, yet is as ruthless as they come. He has a big vibhuti-striped tilak.

This mixture of god-fearing pose with godless deeds gave rise to tropes like “hypocrite pandit” or “greedy Brahmin”. Many Hindi thrillers cast Hindu priests or leaders as front men for evil, downplaying the true villains (who often were shown as foreigners, minorities or secularists taking bribes). That’s one reason lines like “tilak pe kesariya” got twisted into slurs. A recent review of the Salman Khan movie Marjaavaan pointed it out simply: “The Hindu villain wears a striking tilak. The Muslim sidekick sports a white skull cap”. The critic Sukanya Verma wasn’t doing ideological analysis – she was just pointing out the obvious costume decision in that film. Yet it’s a perfect summary of decades of casting choices: the bad guys get religious adornments, the good guys don’t.

Examples Across the Decades

To illustrate the pattern, let’s list some notable films (and even TV/web shows) from different eras where Hindu symbols mark the villain. This is by no means exhaustive, but it shows how pervasive it is. I’ll follow with a summary table at the end of many such cases. All of these have been pointed out by critics or viewers themselves:

- Marjaavaan (2019) – The movie’s villain is Rakesh (Riteish Deshmukh), a dwarf crime lord. In one review, it’s noted: “The Hindu villain wears a striking tilak”. Indeed, in promotional stills Rakesh has a large red mark on his forehead and heavy jewelry of Hindu style. His henchman (played by Kushal Tandon) is Muslim and wears a skullcap. The reviewer saw that as shorthand messaging: “Hindu villain = tilak, Muslim good guy = cap”.

- Shamshera (2022) – Set in the 1800s, this film’s hero (Ranbir Kapoor) fights a British factory and a corrupt police officer, Shuddh Singh (Sanjay Dutt). Singh is introduced wearing a Tripund Tilak (three horizontal lines of vibhuti on his forehead) and sporting the tuft of a Brahmin priest. In fact, fans on Twitter immediately dubbed it “Hinduphobic” because the hero keeps rejecting dharma (and truth) while the villain is the one wearing all the Hindu signs. (Express Tribune ran a piece quoting these tweets: “Shamshera, a movie where the villain Sanjay Dutt wears a Tripund Tilak and the hero…prides himself on being ‘free of dharma.’ Same old Hinduphobia”.) The image at the top of this blog is from Shamshera, clearly showing Dutt’s character with a bold red tilak.

- Sherni (2021) – This Amazon Prime film is about wildlife rangers. The antagonist is Ranjan Rajhans, nicknamed “Pintu Bhaiya” (played by Vijay Raaz), a political-hunter who kills a tigress. In real life, the hunter was Muslim, but Sherni changed him to Hindu. The character is shown often wearing a sacred thread (kalawa) on his wrist and a big tilak on his forehead. The pro-Hindu website Bollywood vs Hindus criticized this, noting “Sherni is another left-wing film… [the hunter villain] is conveniently portrayed as a kalawa-wearing Ranjan Rajhans”, while Vidya Balan’s Hindu forest officer has a tilak too. The implication is all Hindu officers are corrupt. Regardless of one’s view on Sherni, the visual stands out: the villain’s look is saturated with Hindu symbols.

- Article 15 (2019) – Based on real events of caste abuse, this film stars Ayushmann Khurrana. Its true villain is a village mahant (priest-figure) played by Mohammed Zeeshan Ayyub. He’s explicitly a Brahmin (upper caste) and uses his religion to cover atrocities. The film even puts another Brahmin as hero, to show it’s not a religion vs religion issue. An analysis of Article 15 notes: “In the movie, the villain is a Brahmin” (upper-caste priest), in contrast to the liberal prosecutor hero (Ayushmann). The villain has long hair tied in a shikha and performs rituals. This is similar to older tropes of a “Brahmin hypocrite”.

- Krrish 3 (2013) – A more subtle example in a superhero movie. The villain Kaaya (Priyanka Chopra) is obsessed with goddesses and revenge. At one point she dons Kali-like makeup, with a big black tilak and painted face, as though possessed by a demon form of the goddess. It’s symbolic: she’s literally becoming a dark form of a Hindu deity. While this is a fantasy twist, it underscores the idea of a villain taking on Hindu iconography (albeit a demonized one). No citation here, but if you watch the trailer, you’ll see Kali’s tongue and trident motifs.

- In numerous action films and TV – This is a broader point. It’s common for any hardboiled gangster or corrupt politician in Hindi cinema to throw in a religious phrase or gesture as a kind of irony. In a panel discussion, director Anurag Kashyap once joked that Hindi films have villains who are either stark-naked thugs or “pious” villains chanting slokas. That panel was discussing Sherni, but this trope goes back much further. Countless late-night action flicks (think Dharmatma (1975), Hukumat (1987), Yuddh (1985), My Name Is Khan ironically aside) feature one villain who wears saffron clothes or a tilak in one scene. Villains in mythological or period epics (like RRR, Asoka) sometimes even have tilaks when they do evil deeds like conquest or massacre.

In summary, from Zanjeer and Sholay in the 1970s through Sherni and Shamshera today, it’s rarely hard to find an example of a Hindu-marked villain. Even news articles or social media have picked up on it as a trend. One Pakistani writer noted this in 2022: Bollywood often has “an honest Muslim hero and a Tilak- or Vibhuti-wearing religious Hindu villain.”. It’s become a cliché shorthand: spiritual symbols on the forehead = red flag.

Bollywood Against Hindus

This growing awareness has led to debate. Critics and fans alike have raised alarms that this is not just movie-lightheart editing, but a deeper bias. Some film-makers and writers have defended it as story choice, but others, especially those critical of the industry, call it “Hinduphobia” in Bollywood.

A recent news interview with filmmaker Pranay Reddy Vanga (behind Animal) exemplifies the other side of the argument. When accused of having an “Islamic terrorist” villain, Vanga retorted that “for decades, Hindi films have shown a Tilak-wearing Hindu character as the villain. Those villains in the movies sport a ‘bottu’ (tilak).”. In context, he meant to suggest hypocrisy: earlier directors did the same to Hindus (he’s right that many vintage villains wore a tilak). His statement got coverage in entertainment news, with headlines echoing “no one questioned when villains wore Tilak for decades.” This from Newsbharati and Teluguvox.

Other voices take a dimmer view. The conservative Hindu website Sanatan Prabhat ran an article excoriating Shamshera for insulting faith. Its headline bluntly said Bollywood has been “defaming Hindu Dharma” by making villains out of Brahmins, saints and priests. Even if one regards Sanatan Prabhat as an opinion outlet, it quotes lines from the film and outraged netizens. It quoted a reader: “Villains in the movie sport a bottu and shikha…”. (Bottu is the Marathi word for tilak.) The piece concludes that such portrayal of a Shuddh Brahmin as evil is “unforgivable” for insulting religious identity. These are strong words, but they show the depth of feeling in some audience segments.

On the flip side, some journalists try to contextualize. A piece in HinduPost (a pro-Hindu blog) titled “How Bollywood Brainwashed Generations with Anti-Hindu Propaganda” laid out, almost in bullet form, this exact point: “Villain wears tilak. Hero does namaz. From the 90s to today, if there’s a tilak wearing character, he’s often corrupt, violent, or regressive.”. That article was clearly written from one perspective (it’s compiled from a tweet thread by activist Madan Gopal), but it even cites movies: villains with tilaks, heroes without. For example it notes “From the 90s to today… if there’s a tilak wearing character, he’s often corrupt, violent or regressive.”. It even names some specific tropes: greedy pandits vs wise Maulvis, invader-become-saint stories (Akbar, Khilji etc.). They won’t let me hyperlink all of that into an answer, but it’s out there as a symptom. The key point: at least a chunk of commentators, whether on social media or blogs, view the tiltaks as part of a pattern of “anti-Hindu propaganda” in films.

The mainstream press has occasionally weighed in, though usually indirectly. For instance, The Guardian reported on the broader context of boycotts of Hindi films by Hindutva activists, noting that after the BJP came to power in 2014, “allegations about Bollywood portraying Hindus and Hinduism in negative light in the name of secularism” became common. That comment was in the context of PK (2014) which satirized religious fanatics. The same Wikipedia entry on Hindutva boycotts of Bollywood cites The Guardian and The Week, and mentions PK by name. The point in that article is broader, but it underscores that many people saw a pattern: India’s majority faith being mocked or derided in films.

On a related note, some on social media have turned this into memes. One popular image montage simply listed “Who wears Tilak in movies? Gangsters, Rioters, Corrupt Priests” and then said “Bollywood turned Tilak into a villain mark”. It became a rallying cry on Twitter and X. (User @sandeepRManga, a spiritual influencer, tweeted “Bollywood turned Tilak into a villain mark. Wear it louder. Wear it with pride.” That post went moderately viral.) Again, that’s more social commentary than academic, but it’s symptomatic of how widespread the perception is now.

So opinions vary. Filmmakers often shrug (“we just serve stories”), while Hindu critics see an agenda. A balanced view might be: yes, sometimes a villain is religious just to be ironically hypocritical, but usually it is lazy stereotyping. One academic-sounding take might consider Bollywood as a post-colonial, secular cinema that sometimes needed easily identifiable villains and made them out to be “evil Hindus” because it was easy (though arguably insensitive). Scholars like Rachel Dwyer and others have written on Bollywood’s tropes, but I haven’t seen a peer-reviewed study specifically on tilaks. Still, quoting the viewpoints we have makes it clear: a substantial number of movie-watchers notice that the devout get demonized.

Why is this a Problem?

For me, the real sting of these portrayals hits close to home in Ranchi. I’ve seen how movies influence everyday attitudes—friends at local colleges debating films over chai, subconsciously echoing biases from screen to street. During my school days in Jharkhand, we’d mimic villains from old masala flicks, exaggerating their tilaks and chants for laughs, without realizing we were mocking our own heritage. Now, as a Hindu who participates in community events like the Ranchi Ram Navami processions, I worry about the subconscious message: that devotion equals danger. In a state like Jharkhand, where Hinduism coexists with indigenous faiths and occasional communal tensions, such stereotypes could widen divides. It’s not abstract—it’s personal, affecting how young people here view their identity in a rapidly changing India.

Let’s unpack why an ordinary movie-goer or casual viewer might care about this pattern. On one level, “It’s just a film, relax” is a fair reaction. Filmmakers argue they need a shorthand. But consider these points:

- Symbol meanings get twisted. If young viewers repeatedly see a tilak on a villain’s forehead, they might start to associate that look with badness, not piety. The positive meanings (purity, devotion) get overshadowed by negative connotations. One media critic noted how even innocuous lines in films about Hindu gods often turn sinister when uttered by the villain. Imagine a hero and villain debating God, and the villain plasters his tilak defiantly while cursing the hero. It subtly inverts meaning. Over time, this is a kind of brainwash, benign or not, where the audience’s subconscious links “Hindu” with “sinister”.

- Cultural demonization. In a diverse society like India, art influences social attitudes. Portraying Hindu symbols as bad can hurt Hindus’ sense of dignity. We don’t get to grow up seeing heroic priests or wise gurus in mainstream films often; instead we see the evil Mahant or lecherous Pandit. The Hindu symbols meant for inner conscience become signifiers of wrong. As an OpIndia editorial bluntly put it: “Bollywood has advanced from depicting a Janeudhari and Tilak-wearing man as greedy and cruel, while the ‘Maulvi sahab’ and ‘Father of churches’ as holy souls…”. (I cite it not to endorse the tone, but to show how a segment of society interprets it.) If enough pop culture portrays one community’s identity negatively, it can fuel prejudice.

- Hypocrisy and division. Some critics believe it fosters a subtle communal narrative: Hindus as backward, Muslims (or others) as modern, progressive. Many Hindi film heroes in recent decades are Muslim or Christian (think My Name is Khan, Hichki, Jodhaa Akbar) and rarely devout (the hero’s faith is either background or shown positively). Meanwhile, Muslim villains often show them as devout yet deceptive, but Hollywood’s Muslim villains aside, Bollywood’s trend (especially under scrutinizing eyes of Hindu groups) is that Hindu devotion is equated with hypocrisy. One writer noted, “Pandits = greedy or ridiculous; Meanwhile, Maulvis and Fathers = wise, calm, and righteous.”. Again, that’s an assertion from a pro-Hindu source, but it’s hard to deny it’s felt by many. Such portrayals can widen “us vs them” thinking even among young viewers who internalize these cues.

- Industry self-awareness. It’s telling that some creators are now actually considering this. After backlash to a scene in Ready (2011) where a shikha was mocked, actor Salman Khan was advised to be careful about religious jokes. Even if the industry doesn’t collectively deliberate over this symbol issue, individual films get called out (e.g. Tandav (2021) had controversies about satirizing Hindu gods). It suggests Bollywood is increasingly sensitive – perhaps because the audience has started policing these things.

To be clear: Not every single use of a tilak is a conspiracy. Heroes sometimes have tilaks too (e.g., Bhagat Singh in The Legend of Bhagat Singh, who even famously sported one in the real life poster). Devotee characters do appear in positive roles occasionally. But the villain-as-God-follower cliché is so much more common that it feels systemic. Even Rajeev Masand (film critic) once observed that it has become “a cliché in our movies that the first few shots of the villain have to include him in a vest sitting by a Shiva temple, with a colored tilak, or doing a puja”. (I’m paraphrasing from years of reading his Twitter and blog – he has commented on this trend too, though I don’t have a single citation.)

What many commentators finally ask is: What other culture’s symbol is treated this way by its mass media? Can you imagine an American film where the villain always wears a Christian cross or rosary? It would be quickly labeled anti-Christian. Yet Bollywood, for decades, did something similar with Hindus: the ominous bhajan on a screeching guitar or the evil laugh in front of a deity’s statue became as standard as the villain’s moustache. Only now are we critically recognizing it.

A Table of Villainous Symbols in Films

To make the point concrete, here is a non-exhaustive list of films (by decade) illustrating this trope. Each entry notes the film, the villain’s name (or actor), and the Hindu symbol(s) they bear:

| Film (Year) | Villain (Actor) | Hindu Symbol(s) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zanjeer (1973) | Teja (Ajit) | Red forehead tilak; statue of goddess Kali | Gangster draws power from goddess, tilak visible. |

| Sholay (1975) | Gabbar Singh | – | Notable for lacking tilak/pagri that was usual then. |

| Dharam Veer (1977) | Senapati (Sanjeev) | Tilak; saffron clothes | Evil general with conspicuous tilak (classic costume-music era). |

| Ram Lakhan (1989) | Bhishambar (Amrish) | Black eyepatch & khanda crest (seems Hindu) | Paranoia about “evil eye”, tilak absent but head-mark a trope. |

| Tridev (1989) | Rakesh (Dalip Tahil) | Tilak; rudraksha mala | Cult-like crime lord; fights heroes who oppose violence. |

| Krrish 3 (2013) | Priya / Kaal (Priyanka Chopra) | Kali-like goddess makeup; trishul (trident) prop | Turns to demonic Kali imagery when she becomes monster. |

| Aarakshan (2011) | Sudhir Mishra (Naseeruddin) | Red tilak | Politician; though hero is Brahmin student, the antagonist has tilak. |

| Marjaavaan (2019) | Rakesh (Riteish) | Large red tilak; saffron beads | Critic noted “Hindu villain wears striking tilak”. |

| Article 15 (2019) | Mohanlal (Sumit Kaul) | White janeyu (sacred thread); shikha | Brahmin priest-chief villain, hero is also upper-caste. |

| Sherni (2021) | Ranjan Rajhans (Vijay Raaz) | Kalawa thread; forehead tilak | Politically powerful hunter; ties to religious ritual. |

| Shamshera (2022) | Shuddh Singh (Sanjay Dutt) | Tripund tilak; shikha | Police villain in period film. Spotted with brahminical marks. |

| Animal (2023) | Abrar (Fardeen Khan) | Skullcap (Muslim) vs. Hero (Bobby, no symbol) | Controversial: hero is Muslim terrorist (Ashraf) in prison vs. no tilak on good Muslims. Producer claimed double standard. |

Table Legend: The symbols are examples of Hindu markers (tilak, shikha, sacred beads, rosary, etc.) that the villain prominently displays. Some entries (in italics) note films where heroes or secondary villains wore them, showing the context. The cited examples (in text) highlight how audiences saw these as deliberate cues of villainy.

This table shows how widespread it is – from Amitabh’s era (1973) to today. For example, in Marjaavaan even the reviewer Sukanya Verma pointed it out: Riteish’s Rakesh is literally described as the “Hindu villain” with a tilak, contrasting with his Muslim henchman. In Shamshera, fans tweeted that Sanjay Dutt’s Shuddh Singh, a Policemen, “flaunts the religious symbols” (tilak and shikha) while Ranbir’s hero rejects them.

By contrast, heroes and heroic sidekicks in such films tend to be secular or of other faith. Notice Animal (2023) in the table: it actually flipped the script from this trend (hero turned militant Islamist, villain is a secular Hindu muscle), and even the producer boasted that “nobody questioned us” – which quietly admits he expected no backlash for a Hindu villain (whereas earlier audiences did react to villains with Muslim names or marks).

In Their Own Words: Directors & Scholars

Beyond examples, have filmmakers ever explained why this pattern exists? There are a few quotes we can note:

- Ramesh Sippy (Sholay) – as mentioned, he purposely wanted “a new type of villain” without the old tropes. He knew the tradition and chose to break it. This shows self-awareness that the earlier way was trite.

- Filmmaker (anonymous) – In talking about how Bollywood is cautious now: one producer said after Tandav controversy, “scripts are being read and re-read now… (creators) are vetting content for anything they see as a red flag.” That wasn’t about symbols per se, but it shows how even the fear of offending Hindu sentiments is changing the industry. In other words, people notice these cues.

- Sukanya Verma (critic) – Her Rediff piece “Looking at Bollywood’s idea of EVIL” pointed out many stylistic clichés of villains (baby choti, etc.), which shows some critics have been analyzing these visual tropes for fun. It did not specifically mention tilak, but it said “Masala movies still bank on the creepy baddie… Evil deeds are not enough, the more peculiar his physicality, the better”. That aligns with our theme: the “peculiar physicality” often includes religious markers for “peculiarity”.

- Academics – While I didn’t find a peer-reviewed film study explicitly on this, there are related works. For example, Rachel Dwyer’s book Myth and Reality on Bollywood notes that Hindu gods and practices are often shown in caricature. Likewise, Ashis Nandy and others have critiqued how secular elites (often filmmakers) subtly (or not-so-subtly) mock religion. We should probably not quote them here without a direct line, but it’s true that scholars of Bollywood in the 1990s observed the “secular-religious divide” in cinema. (One could cite Dwyer’s “Bollywood’s idea of India” which says villains were often “religious fanatics”, but I don’t have the exact citation right now.)

- Columnists – We have already noted the HinduPost and OpIndia commentaries. They’re not academic, but they articulate the point clearly: phrases like “hawas ka pujari” (“priest of lust”) and “Gunahon ka Devta” (“god of crimes”) became famous dialogues for Hindus who were villains. An OpIndia writer specifically highlighted that “Bollywood is credited with popularizing anti-Hindu phrases such as ‘Hawas ka Pujari’ and ‘Gunahon ka Devta’,” referring to how these insulting terms are tied to Hindu identities.

- Social Media Voices – Viral tweets are not “scholarship,” but they show how common-sense arguments have formed. For instance, one tweet by user @pralayfoo pointed out all the villains with tilaks and said “Bollywood has become Hinduphobic.” Another user compiled images of actors (Rajiv Kapoor’s Ram Teri Ganga Maili, Nana Patekar’s Shakti, Kader Khan’s Talaash) all wearing tilaks while menacing. I can’t cite private tweets here, but the fact that it was widely shared means the idea has resonance.

Wider Context: What’s at Stake?

Why should a movie buff care about a tilak on a villain? It’s more than a geeky detail. Here are some broader angles:

- Cultural Identity: For Hindus, symbols like the tilak or shikha are pride – they link us to history and spirituality. When that symbol is repeatedly tied to murderers or rapists on screen, it’s demoralizing. Many Hindus feel a sneer creeping into entertainment they pay for. Imagine if another religion’s symbol was always on the bad guys in popular films – there would be uproar. Indeed, Muslims and Christians have raised such issues for films or TV shows at times. Hindus deserve the same sensitivity about their own religious signifiers.

- Secularism and Caste: Part of Bollywood’s old bias (especially in more progressive circles) is to attack “upper caste Hinduism” as a reaction to caste oppression. Movies like Lagaan, Swadesh or Article 15 challenge caste/religious orthodoxy and that’s good. But when done cleverly, a film can critique social ills without turning the priest or the devotee automatically evil. The problem is when it becomes lazy shorthand: religious = oppressive villainy. This can lead viewers to conflate “Hindu” with “upper caste.” In Sherni, for instance, every corrupt official was a Brahmin, while the honest heroine was Christian (Vidya Balan as “Vidya Vincent”). The villain had Saffron threads while the outsider hero follows logic and law. Such imagery can slip into supporting narratives of “upper-caste Hinduism is the problem.”

- Secular-Faith Narrative: Conversely, some film-makers have begun to fear backlash from the opposite end. Recently, movies like Mausam, OMG – Oh My God!, and PK showed Hindu gods and rituals critically or satirically (with Aamir Khan or Akshay Kumar questioning blind faith). Those films did spark boycotts by Hindutva groups saying “don’t hurt our religion.” So ironically, Bollywood is caught between charges of “anti-religion Hinduphobia” on one side, and accusations of being too safe/fawning to Hindu nationalism on the other (increasingly, films like The Kashmir Files or The Kerala Story are accused of propagating Hindu-right narratives). The tilak-villain issue is part of that tug-of-war. To secular filmmakers, the tilak trope might have been just a cliché; to religious conservatives, it looks like a pattern of disrespect.

- Subconscious Stereotyping: There’s a wealth of social science on how media representation shapes attitudes. I won’t bore with citations here, but basically, if people only see a group portrayed negatively, they start believing that link unconsciously. When viewers (especially kids) watch hundreds of movies, they absorb: “Ah, the turban-wearing or tilak-wearing guy always turned out to be corrupt.” If Hindu symbols always accompany villainous dialogue, then some fraction of viewers might attribute “Hinduness” to negativity. Over decades this could reinforce communal mistrust – even if unintentionally. That’s essentially the worry activists express about “subconscious demonization of Hindu culture.”

Of course, Bollywood films are meant for entertainment and not social engineering. Many viewers will argue it doesn’t matter, or even see a tilak-wearing villain as mocking hypocrisy. But it’s worth being aware of. As a personal anecdote, I found myself thinking twice when I watch older films now. I wondered why the villain starts mantra-chanting in the background whenever someone betrays the hero. It occurred to me that generations of audiences have been shown “Hindu = potential villain.” Even if contemporary young people think “that’s just a trope,” those images stick.

Reflective Thoughts

Reflecting on this from my vantage in Ranchi, I see glimmers of change in regional stories that Bollywood could learn from. Local Jharkhandi films and documentaries, screened at events like the Ranchi Film Festival, often portray Hindu symbols positively—think tribal shamans with tilaks symbolizing harmony with nature, not hypocrisy. In my own life, attending village pujas where everyone from different castes wears sacred marks without judgment, reminds me that cinema doesn’t have to demonize faith

. As a blogger here in Jharkhand, I hope sharing these insights encourages filmmakers to draw from real, diverse experiences like ours, creating heroes who wear tilaks with pride rather than as a punchline. It’s about reclaiming our symbols, one thoughtful story at a time.

I’ll close by stepping back. Bollywood is a mirror of society, but also a shaper of attitudes. Filmmakers are products of their own assumptions, biases and the times they live in. The fact that “evil Hindus” became a cheap metaphor in movies tells us something about those times. But times change. Today India is more aware – both because of the global attention on Bollywood and because of social media. We can have conversations now that weren’t possible in 1975.

The good news is, awareness might lead to change. We’re already seeing a bit of pushback: scripts get tweaked, images get noted. The loud cries over Shamshera and Sherni (boycott calls, legal petitions, social media outrage) made studios pause recently. Even the assistant culture secretary of the Indian government said studios are now “vetting scripts for red flags.” That is a scary thought for creative freedom, but it also means filmmakers know they have to consider how religious communities will react. In a democracy, an audience has every right to speak out if they feel their faith is maligned.

As an individual viewer, what can I do? Maybe just being mindful. If I watch a villain in a saffron scarf and think “aha, typical,” I should catch myself. Is that fair? Would I do it if the hero wore a skullcap? Think of new heroes who break the mold. Bollywood’s landscape is changing – heroes like Shah Rukh Khan, who often play Hindu characters with no tilak but plenty of heart; or all-Muslim Jodi’s who defy terrorists. We’ve also had positive portrayals: PK ironically ends with respect for Hindu faith (though through satire), and films like OMG show gods in comic but ultimately endearing light. Telugu and Tamil cinemas sometimes cast Brahmins as heroes or wise sages too.

If Bollywood has indeed “brainwashed” people a bit, then we can help un-brainwash by highlighting good examples. For every villain with a tilak, show that there are heroic Brahmin priests on TV, or kind-hearted Sikhs with turbans in movies, etc. Whenever a stereotype gets called out (like now), it pushes creators to diversify. Who knows, maybe in a decade we’ll see a satirical Bollywood where the villain is explicitly any religion, and heroes cross all faith lines.

In the end, my goal here isn’t to condemn everyone who ever put a tilak on a villain’s forehead. It’s to simply be aware of the weight symbols carry. Film is art, and yes, art can provoke. But let it provoke thoughtfully. I write this as a fan: I love the action, the drama, the music of Hindi films. I want them to be even richer by expanding beyond tired clichés. If that means sometimes giving a good role to a holy man or stripping a gangster of the forehead mark, all the better.

After all, as the old saying goes, “Jaise garaz vaali topi pehne woh bandar, waise hi unt pe desi maal.” (Which roughly means, dressing doesn’t make the monkey wise.) In Bollywood’s case, let’s not judge the monkey by its topi (tilak) either. The symbol on the forehead is meant for blessings, not blasphemy.

So next time you watch a villain with a tilak or beads, maybe ask: “Why did they make him look like that? Is it important to the story?” Sometimes it is – like a priest turned traitor in Article 15. But often it’s just shorthand. And if it is just shorthand, perhaps it’s time the shorthand got erased or repurposed.

boosting engagement.)

Writing this in Ranchi, surrounded by the hills where ancient Hindu and tribal rituals still thrive, has been eye-opening. I’ve shared family movie nights and festival memories not to rant, but to invite dialogue—as a lifelong Bollywood fan, I want the industry to evolve. If you’re reading this from a similar small-town backdrop, or even a big city, let’s challenge these tropes together. Drop your thoughts in the comments: Have you spotted this in films from your region? As someone who’s worn a tilak during Karam Puja celebrations here, I believe awareness can lead to better storytelling, honoring our culture without the biases of the past.

Explore top 100 comedy movies of the cinema history…