— Quentin Tarantino

Introduction

There are very few writer-directors who have so completely fused personal obsession, encyclopedic film knowledge, and unapologetic bravado into a singular cinematic voice that their work becomes instantly recognizable within minutes. Quentin Tarantino is one of those rare figures. His films don’t just tell stories; they announce themselves. A Tarantino movie arrives with a rhythm, an attitude, a smell of celluloid nostalgia mixed with pop-culture swagger. Whether you love him or loathe him, it is impossible to deny that modern cinema looks the way it does in part because Quentin Tarantino decided, in the early 1990s, to break every rule that filmmakers were politely following.

Growing up in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, I discovered Tarantino the way most of us in smaller cities did—through pirated DVDs and late-night cable channels. My first Tarantino film was Pulp Fiction, watched on a grainy VCD at a friend’s house in 2005. I was 15, and the nonlinear structure, the casual violence, the endless pop-culture references completely blew my mind. In a place where mainstream Bollywood dominated every theater and TV screen, Tarantino felt like a secret rebellion. He showed me that cinema could be loud, irreverent, and deeply personal. That experience shaped how I watch and write about movies to this day.

This article explores Tarantino in depth: how he redefined modern cinema, his controversial approach to violence, his masterful worldbuilding and dialogue, his experimental storytelling choices, his complete filmography, critiques of his filmmaking, his self-imposed ten-film rule, and—most importantly—what aspiring writers and directors can learn from his career. This is not a surface-level appreciation. This is a deep dive into the mind of a filmmaker who turned obsession into art and rebellion into a career.

How Quentin Tarantino Defined Modern Cinema and Inspired a Generation

Before Tarantino, American independent cinema existed largely on the margins—earnest, small, often apologetic. Films like sex, lies, and videotape (1989) or Clerks (1994) were groundbreaking but still felt like underdog stories. After Tarantino, indie cinema swaggered. Reservoir Dogs (1992) didn’t feel like a debut film; it felt like a declaration of war against conventional storytelling. Made on a shoestring budget of $1.2 million, it grossed over $2.8 million domestically and became a cult phenomenon. More importantly, it proved that dialogue could be more gripping than action, that structure could be fractured without losing coherence, and that genre cinema could be intellectual without becoming pretentious.

Tarantino reintroduced audiences to the idea that movies could openly converse with other movies. He didn’t hide his influences—he flaunted them. Hong Kong action cinema (John Woo’s bullet ballets), Italian spaghetti westerns (Sergio Leone’s extreme close-ups), French New Wave (Godard’s jump cuts), grindhouse exploitation, blaxploitation (Shaft, Super Fly), kung-fu films (Bruce Lee, Shaw Brothers)—all collided in his work. Instead of being accused of imitation, he reframed borrowing as curation. He was a DJ sampling cinema history and remixing it into something ferociously new.

In Jharkhand, where access to world cinema was limited until streaming arrived, Tarantino’s films felt like a gateway to global movie history. When I finally watched The Good, the Bad and the Ugly or Enter the Dragon years later, I realized half the joy of Tarantino was recognizing the references. It taught me that loving movies deeply isn’t nerdy—it’s essential. That realization changed how I approach film writing and criticism.

An entire generation of filmmakers learned from Tarantino that originality doesn’t mean ignorance of the past. It means obsession with it. Directors like Paul Thomas Anderson (Boogie Nights, Magnolia), Edgar Wright (Shaun of the Dead, Baby Driver), Guy Ritchie (Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels), the Safdie brothers (Uncut Gems), and countless indie filmmakers were emboldened to embrace stylization, nonlinear narratives, needle-drop soundtracks, and sharp dialogue because Tarantino proved that audiences were hungry for bold voices. Even Marvel borrowed his chapter structure and pop-culture banter in films like Guardians of the Galaxy. Tarantino didn’t just influence cinema—he changed its DNA.

Violence as Art: Tarantino’s Philosophy and Kill Bill

Violence in Tarantino’s films has always been the lightning rod for criticism. Blood sprays, limbs are severed, bullets tear through bodies—but rarely is the violence realistic. It is theatrical, exaggerated, almost operatic. Tarantino once addressed criticism of his violent style in a video interview, famously saying:

“I love violence in cinema—not because of cruelty, but because of its expressive power. It’s like music. It has rhythm, it has crescendo, it has emotion.”

In Kill Bill (2003–2004), violence becomes choreography. The Bride’s massacre of the Crazy 88 isn’t meant to simulate real death; it’s meant to feel like a live-action comic book filtered through samurai cinema. Black-and-white photography, sudden animation sequences, exaggerated sound effects, the iconic House of Blue Leaves fight scene—Tarantino strips violence of realism and transforms it into pure cinematic sensation. The film is a love letter to martial arts, samurai, and exploitation cinema, and the violence is deliberately stylized to honor those traditions.

Critics who accuse Tarantino of glorifying violence often miss this key distinction: his violence is symbolic, not instructional. It exists in a heightened cinematic universe where moral consequences are abstract rather than procedural. He doesn’t ask, “Is violence good or bad?” He asks, “What does violence feel like on screen?”

As someone who grew up watching gory Bollywood action films (think Ghatak or Gadar), I was never squeamish about violence. But Tarantino’s style felt different. It was playful, almost joyful. When I first watched Kill Bill in college, the Crazy 88 fight scene made me laugh and gasp at the same time. It reminded me that cinema can make brutality beautiful without endorsing it. That lesson stayed with me—violence on screen can be art when it’s honest about its artificiality.

By leaning into excess, Tarantino exposes the artificiality of movie violence itself. His films force audiences to confront their own appetite for cinematic brutality. The discomfort is the point.

Worldbuilding: The Tarantino Cinematic Universe

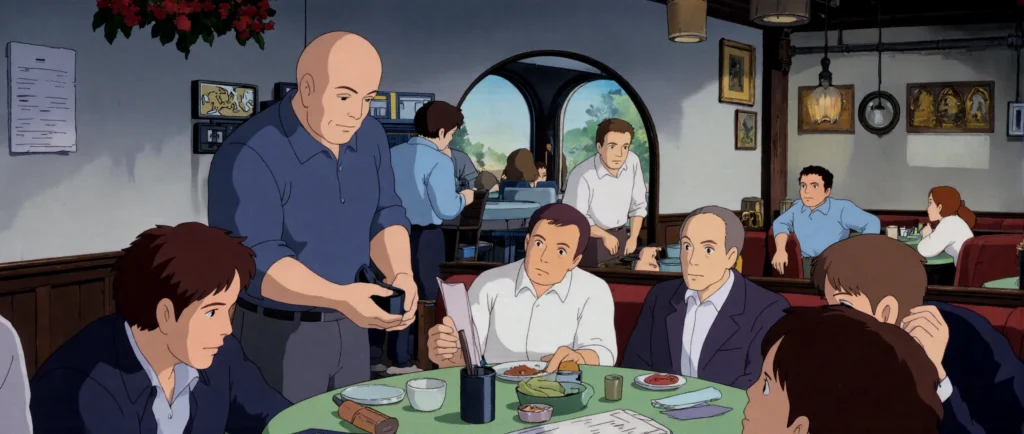

One of Tarantino’s most underappreciated skills is worldbuilding. His films don’t merely take place in locations; they exist in an alternate cinematic reality. A reality where brand names recur (Big Kahuna Burger, Red Apple cigarettes), fictional TV shows exist (Fox Force Five), and characters reference pop culture as if they’re aware of living inside a movie.

Tarantino has openly discussed the idea of a “movie movie universe” and a “realer-than-real universe” within his work. Characters like the Vega brothers (Vic Vega in Reservoir Dogs and Vincent Vega in Pulp Fiction) hint at interconnected timelines. Red Apple cigarettes appear across films, creating continuity without exposition. Even characters from different movies mention the same fictional brands or events.

This worldbuilding doesn’t rely on lore dumps or fantasy maps. It’s cultural. It’s built through conversation, music choices, costumes, and attitude. You feel like Tarantino’s characters existed before the camera turned on and will continue to exist after the credits roll.

Living in Jamshedpur, where we have our own local legends and inside jokes, I love how Tarantino creates a shared mythology across films. When I rewatch his movies, I catch new connections—Red Apple cigarettes in Pulp Fiction and Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, or the mention of the Vega brothers. It feels like being part of a secret club. That sense of continuity is something I try to emulate in my own writing—creating small, recurring details that reward repeat viewers.

Dialogue: Music Made of Words

Tarantino’s dialogue is his most copied—and most misunderstood—trait. It is not realistic in the traditional sense. People don’t usually speak like Tarantino characters. But they feel truthful. The conversations wander, circle, digress, and suddenly explode.

What makes his dialogue special is tension. A casual discussion about burgers in Pulp Fiction becomes terrifying because you know violence is lurking beneath the surface. In Inglourious Basterds, a simple conversation about dairy products becomes one of the most suspenseful scenes in modern cinema. In Django Unchained, the dinner table scene is a masterclass in verbal fencing—every word is a weapon.

Tarantino understands that dialogue is action. Words can threaten, seduce, mislead, and dominate. His characters talk to gain power—and sometimes to lose it.

As someone who grew up in a multilingual household in Jharkhand—Hindi, English, and a bit of Santhali—I’ve always loved how Tarantino’s characters switch languages, slang, and tones mid-conversation. His dialogue feels like real arguments among friends in my city—playful one moment, deadly serious the next. When I write, I try to capture that rhythm: let characters talk themselves into corners, reveal secrets, or just enjoy the sound of their own voices.

Experimental Choices in Storytelling

Nonlinear narratives. Chapter structures. Sudden shifts in tone. Long takes followed by abrupt cuts. Tarantino treats structure as a playground.

Pulp Fiction shattered the idea that stories must move forward in time. Death Proof split itself in half. The Hateful Eight turned a western into a chamber drama. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood rejected traditional plot escalation entirely, choosing mood over momentum.

These choices are not gimmicks. They are expressions of theme. Time bends in Tarantino’s films because memory bends. History rewrites itself (Inglourious Basterds). Revenge replaces realism (Django Unchained). The structure serves the emotion.

Quentin Tarantino Filmography

| Year | Film Title | Role | Key Notes & Achievements |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | Reservoir Dogs | Writer-Director | Sundance sensation; made $2.8M on $1.2M budget; iconic ear-cutting scene |

| 1994 | Pulp Fiction | Writer-Director | Palme d’Or winner; $213M worldwide; revived John Travolta’s career |

| 1997 | Jackie Brown | Writer-Director | Adaptation of Elmore Leonard’s Rum Punch; Pam Grier’s comeback; more restrained violence |

| 2003 | Kill Bill: Vol. 1 | Writer-Director | Love letter to martial arts; Uma Thurman as The Bride; iconic anime sequence |

| 2004 | Kill Bill: Vol. 2 | Writer-Director | More character-driven; emotional payoff; David Carradine’s final major role |

| 2007 | Death Proof | Writer-Director | Grindhouse double feature; car-chase masterpiece; Kurt Russell as Stuntman Mike |

| 2009 | Inglourious Basterds | Writer-Director | Alternate history WWII; Christoph Waltz’s Oscar-winning performance |

| 2012 | Django Unchained | Writer-Director | Spaghetti western; Jamie Foxx, Christoph Waltz; Oscar for Best Original Screenplay |

| 2015 | The Hateful Eight | Writer-Director | 70mm roadshow release; chamber western; Samuel L. Jackson’s tour-de-force monologue |

| 2019 | Once Upon a Time in Hollywood | Writer-Director | Love letter to 1960s Hollywood; Leonardo DiCaprio & Brad Pitt; Oscar for Supporting Actor (Pitt) |

Understanding Quentin Tarantino Through His Films: A Detailed Analysis

Quentin Tarantino isn’t just a director; he’s a cinematic force whose films serve as windows into his obsessions, worldview, and unfiltered creativity. By dissecting his major works—focusing on plot, themes, style, influences, and controversies—we can piece together a portrait of the man: a video-store clerk turned auteur, a pop-culture savant with a penchant for violence, dialogue, and revisionist history. This analysis draws from his nine narrative features (excluding cameos or segments like Four Rooms), revealing a filmmaker who blends homage with innovation, often sparking debate. His films reflect a love for genre cinema, a fascination with revenge, and a provocative stance on race, gender, and history—sometimes brilliant, sometimes regressive. We’ll break it down film by film, then synthesize overarching insights.

Growing up in Jamshedpur, Jharkhand, where Bollywood ruled and world cinema was a rare treat via bootleg DVDs, Tarantino’s films felt like a revelation. His mash-up of influences mirrored the cultural blends I saw in local festivals—Hindi epics mixed with tribal stories. Analyzing his movies helped me understand not just him, but how a filmmaker’s passions can reshape reality.

1. Reservoir Dogs (1992): The Birth of Cool Crime

Plot Summary

A heist gone wrong leaves a group of color-coded criminals (Mr. White, Mr. Orange, etc.) holed up in a warehouse, unraveling paranoia and betrayal. Flashbacks reveal the setup, but the robbery itself is never shown.

Themes & Style

This debut emphasizes dialogue over action—long, meandering conversations about Madonna songs or tipping waiters build tension amid gore. Themes of loyalty, masculinity, and the banality of evil dominate. The nonlinear structure and pop-culture banter set Tarantino’s template: crime as theater. Violence is stylized (e.g., the infamous ear-cutting scene to “Stuck in the Middle with You”), turning brutality into dark comedy.

Influences

Heist films like The Killing (Stanley Kubrick) and City on Fire (Ringo Lam); French New Wave jump cuts; blaxploitation dialogue rhythms.

Controversies

Accusations of plagiarism from City on Fire (Tarantino called it “inspiration”). The torture scene sparked walkouts at festivals, highlighting his “gratuitous” violence.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

A self-taught cinephile turning low-budget constraints into strengths. His love for “bullshit” conversations (as he calls them) shows a fascination with human absurdity amid chaos.

2. Pulp Fiction (1994): Nonlinear Masterpiece

Plot Summary

Interwoven tales of hitmen (John Travolta, Samuel L. Jackson), a boxer (Bruce Willis), a gangster’s wife (Uma Thurman), and petty thieves, all circling a mysterious briefcase.

Themes & Style

Redemption, fate, and pop-culture absurdity. Nonlinear vignettes (e.g., Vincent’s overdose, Butch’s watch quest) create a puzzle-box narrative. Dialogue is iconic—”Royale with Cheese”—blending philosophy with profanity. Needle-drop soundtrack (e.g., “Misirlou”) elevates scenes.

Influences: French New Wave (Godard); blaxploitation (Shaft); Leone westerns (close-ups, tension).

Controversies: Glorification of violence and drugs; frequent N-word use drew ire from Spike Lee, who called it exploitative. Yet it won the Palme d’Or and revitalized Travolta’s career.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

His genius for remixing genres into something fresh. The film’s moral ambiguity mirrors his view: “Cinema is my religion.” It shows a director obsessed with character over plot.

3. Jackie Brown (1997): Subtle Heist Homage

Plot Summary

Flight attendant Jackie (Pam Grier) double-crosses a gunrunner (Samuel L. Jackson) and a bail bondsman (Robert Forster) in a money-smuggling scheme.

Themes & Style

Aging, romance, and cunning survival. Slower pace, character-driven; split-screens and long takes emphasize deception. Soundtrack heavy on soul (e.g., “Across 110th Street”).

Influences

Blaxploitation (Grier’s Foxy Brown); Elmore Leonard’s novel Rum Punch (adapted faithfully).

Controversies

Less violent, but N-word usage persisted, fueling debates on Tarantino’s appropriation of Black culture.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

A maturing artist capable of restraint. His admiration for 1970s icons like Grier shows a deep respect for overlooked talent.

4. Kill Bill: Vol. 1 (2003) & Vol. 2 (2004): Revenge Epic

Plot Summary

The Bride (Uma Thurman) awakens from a coma to hunt her assassins, including Bill (David Carradine).

Themes & Style

Vol. 1 is action-packed (anime, Crazy 88 fight); Vol. 2 introspective (Pai Mei training, emotional confrontations). Themes of motherhood, betrayal, and stylized vengeance.

Influences

Lady Snowblood (Japanese revenge); Bruce Lee (yellow jumpsuit); Shaw Brothers kung-fu; Leone westerns.

Controversies

Extreme violence (e.g., child witnessing murder); Thurman’s 2018 revelations of on-set abuse and a car crash Tarantino forced her into. Critics noted pain evocation beyond gore.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

His love for global genres; violence as “expressive power.” The split volumes show his willingness to experiment with form.

In Jamshedpur, watching Kill Bill on a borrowed DVD felt like a crash course in world cinema. The Bride’s revenge mirrored local folk tales of strong women in Jharkhand’s tribal stories, making Tarantino’s global mash-up feel surprisingly relatable.

5. Death Proof (2007): Grindhouse Thrill

Plot Summary

Stuntman Mike (Kurt Russell) uses his “death-proof” car to murder women, until he meets his match.

Themes & Style

Empowerment, car chases; homage to exploitation with fake scratches and trailers.

Influences

1970s car-chase films (Vanishing Point); grindhouse double-features.

Controversies

Seen as misogynistic (women as victims), though it flips to female triumph.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

His niche obsessions; a fun, low-stakes experiment amid bigger films.

6. Inglourious Basterds (2009): Alternate WWII

Plot Summary

Jewish-American soldiers scalp Nazis; a theater owner plots Hitler’s assassination.

Themes & Style

Revenge fantasy; tension via dialogue (e.g., milk scene). Multilingual, chapter-structured.

Influences

WWII films (The Dirty Dozen); spaghetti westerns.

Controversies

Alternate history offended some (e.g., Russians felt WWII downplayed). Violence as “fun” drew ire.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

His revisionism—rewriting history for catharsis, reflecting a belief in cinema’s power to “fix” reality.

7. Django Unchained (2012): Slavery Western

Plot Summary

Freed slave Django (Jamie Foxx) rescues his wife from a plantation with a bounty hunter (Christoph Waltz).

Themes & Style

Racial justice, revenge; brutal depictions of slavery mixed with humor.

Influences

Spaghetti westerns (Django series); blaxploitation.

Controversies

N-word overuse; Spike Lee boycotted it as disrespectful to slavery. Seen as flippant or empowering.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

Bold tackling of race; “revenge permeates his work.” Shows his provocative edge.

8. The Hateful Eight (2015): Chamber Western

Plot Summary

Bounty hunters and outlaws trapped in a blizzard uncover betrayals.

Themes & Style

Paranoia, racism post-Civil War; 70mm format for intimate scope.

Influences

Reservoir Dogs (warehouse tension); westerns like The Thing (paranoia).

Controversies

Graphic violence; police boycott after Tarantino’s anti-brutality comments.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

Mastery of confined spaces; themes of division mirror his social views.

9. Once Upon a Time in Hollywood (2019): Hollywood Nostalgia

Plot Summary

Fading actor Rick Dalton (Leonardo DiCaprio) and stuntman Cliff Booth (Brad Pitt) navigate 1969 LA amid Manson murders.

Themes & Style

Nostalgia for 1960s Hollywood; alternate history ending.

Influences

Leone (Once Upon a Time titles); 1960s TV westerns.

Controversies

Regressive white-male focus; Bruce Lee caricature; glorifying violence against hippies.

What It Reveals About Tarantino

Yearning for “lost” Hollywood; his “obscenely regressive” nostalgia.

Overarching Themes & Influences

Themes

Revenge as redemption; alternate histories (fixing injustices); pop-culture as philosophy; stylized violence as “art.” Race and gender are recurrent, often controversially.

Influences (Expanded from Prior):

Hong Kong (Woo), spaghetti westerns (Leone), blaxploitation, French New Wave (Godard), grindhouse, Japanese samurai, film noir. He “steals from every movie ever made.”

Controversies Summary

Violence as “gratuitous” yet expressive; racial slurs (N-word in multiple films); gender issues (e.g., Thurman crash); cultural appropriation. Defenders see it as ironic commentary; critics as irresponsible.

| Film | Key Theme | Major Influence | Controversy Highlight |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reservoir Dogs | Betrayal & Masculinity | Heist films (The Killing) | Plagiarism claims |

| Pulp Fiction | Fate & Redemption | French New Wave | Racial slurs |

| Jackie Brown | Survival & Aging | Blaxploitation | Cultural appropriation |

| Kill Bill | Revenge & Empowerment | Samurai/kung-fu | On-set injuries |

| Death Proof | Female Triumph | Grindhouse car chases | Misogyny accusations |

| Inglourious Basterds | Historical Revenge | WWII ensemble films | Alternate history offense |

| Django Unchained | Racial Justice | Spaghetti westerns | N-word overuse |

| The Hateful Eight | Paranoia & Division | Chamber dramas | Police boycott |

| Once Upon a Time in Hollywood | Nostalgia & Loss | 1960s Hollywood | Regressive views |

Understanding Tarantino Through His Films

Tarantino emerges as a obsessive curator—his films are collages of cinema history, reflecting a video-store education. He’s provocative, using violence and slurs to challenge norms, but often accused of insensitivity. His revisionism (e.g., killing Hitler, avenging slavery) reveals a desire to “right wrongs” via fantasy. Ultimately, he’s a cinephile’s cinephile: films about films, where style is substance.

In Jamshedpur, Tarantino’s films taught me to see cinema as a conversation across cultures. His bold takes on history inspired me to question Bollywood tropes, much like our local stories challenge mainstream narratives. He’s flawed but fearless—a reminder that great art provokes.

Quentin Tarantino’s Influences

Tarantino’s genius lies not in inventing cinema from scratch, but in how he absorbs, honors, and transforms the entire history of film into something unmistakably his own. He has never hidden his influences—in fact, he flaunts them. Every Tarantino film is a love letter, a remix, and sometimes a respectful theft from the movies that shaped him. He once famously said: “I steal from every single movie ever made.” But what he steals, he elevates.

Here are the major cinematic influences that run through his work, grouped by genre and style, with specific examples of how they appear in his films.

1. Hong Kong Action Cinema & Martial Arts Films

- Key Directors: John Woo, Chang Cheh, King Hu, Tsui Hark, Shaw Brothers studio

- Signature Elements: Bullet ballets, slow-motion gunfights, choreographed swordplay, extreme stylization

- Tarantino’s Use:

- The entire Kill Bill saga is a direct homage to Hong Kong kung-fu and wuxia cinema. The House of Blue Leaves fight is straight out of a Shaw Brothers film, complete with anime sequences (inspired by Japanese anime like Lady Snowblood) and the use of black-and-white for dramatic effect (a nod to King Hu’s A Touch of Zen).

- The “bullet time” slow-motion shootouts in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction owe a debt to John Woo’s The Killer and Hard Boiled.

Growing up in Jamshedpur, I first fell in love with martial arts through pirated VCDs of Bruce Lee and Jet Li movies. When I watched Kill Bill for the first time, I felt like Tarantino was speaking directly to that 15-year-old kid in me who dreamed of sword fights and revenge. It made me realize that loving “lowbrow” genres like kung-fu wasn’t something to be ashamed of—it could be the foundation of high art.

2. Italian Spaghetti Westerns

- Key Directors: Sergio Leone, Sergio Corbucci, Duccio Tessari

- Signature Elements: Extreme close-ups, long silences, operatic scores (Ennio Morricone), morally ambiguous anti-heroes

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Django Unchained is his most explicit spaghetti western tribute, complete with Morricone music (some tracks reused from old films), wide desert landscapes, and a bounty-hunter protagonist.

- The Hateful Eight is a chamber western—Leone’s close-ups meet Corbucci’s bleak violence in a snowbound cabin.

- The opening credits of Inglourious Basterds use Morricone’s music from The Big Gundown.

- In Jharkhand, where we have our own oral storytelling traditions of epic battles and revenge, the spaghetti western’s larger-than-life heroes and villains felt strangely familiar. Tarantino’s love for Leone made me appreciate how universal the language of revenge and justice can be, no matter where you’re from.

3. Blaxploitation & 1970s American Genre Cinema

- Key Films/Directors: Shaft (1971), Super Fly (1972), Foxy Brown (1974), Pam Grier, Fred Williamson

- Signature Elements: Funky soundtracks, cool anti-heroes, urban crime stories, racial empowerment

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Jackie Brown is his love letter to blaxploitation, starring Pam Grier (the queen of the genre) and featuring a soundtrack full of 1970s soul.

- Django Unchained reimagines the blaxploitation revenge fantasy on a grand scale.

- Samuel L. Jackson’s characters (Jules in Pulp Fiction, Ordell in Jackie Brown, Stephen in Django) carry the swagger of blaxploitation heroes.

- As someone who grew up in a small industrial city in India, the idea of a cool, confident Black hero taking on the system felt revolutionary. Tarantino’s revival of blaxploitation gave me permission to celebrate “low” genres and see their political power.

4. French New Wave & European Arthouse

- Key Directors: Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut, Jacques Demy

- Signature Elements: Jump cuts, breaking the fourth wall, self-reflexivity, playful tone

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Pulp Fiction’s nonlinear structure and chapter titles echo Godard’s Breathless and Bande à Part.

- The dance scene in Pulp Fiction (John Travolta and Uma Thurman) is a direct homage to Bande à Part’s famous dance sequence.

- Tarantino’s constant references to other films within his own (characters talking about movies) is pure New Wave self-awareness.

- The French New Wave taught me that cinema could be intellectual and fun at the same time. Tarantino showed me that you don’t have to choose between being smart and being entertaining.

5. Grindhouse & Exploitation Cinema

- Key Genres: Drive-in horror, biker films, women-in-prison movies, car-chase exploitation

- Signature Elements: Cheap production values, over-the-top violence, sensational posters

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Death Proof (part of the Grindhouse double feature with Robert Rodriguez) is a loving recreation of 1970s exploitation car-chase films.

- The fake trailers in Grindhouse (Machete, Werewolf Women of the SS) are pitch-perfect homages to grindhouse advertising.

- In Jamshedpur, we had video parlors that showed all kinds of B-movies—everything from Hong Kong action to Italian cannibal films. Tarantino’s love for grindhouse made me realize that those “trashy” films I watched as a teenager were actually art in disguise.

6. Other Notable Influences

- Japanese Anime & Manga: Kill Bill’s anime sequence, O-Ren Ishii’s backstory

- American Crime Films (1970s): The French Connection, Dirty Harry, The Getaway

- Brian De Palma & Scorsese: Stylized violence, long tracking shots, Catholic guilt undertones

- Melville & French Crime: Cool, detached criminals (Le Samouraï, Le Cercle Rouge)

Personal reflection: Tarantino’s influences are like a map of my own cinematic education. From pirated kung-fu VCDs in Jamshedpur to discovering Godard and Leone through YouTube, his films made me realize that loving movies—really loving them—is the best film school there is. He taught me that you don’t need to be “original” in a vacuum; you just need to love deeply, steal shamelessly, and make it your own.

Quentin Tarantino’s Music Influences: The Soundtrack of a Cinematic Visionary

Quentin Tarantino doesn’t just use music in his films—he weaponizes it. His soundtracks are as much characters as the actors on screen. He treats songs not as background filler, but as narrative engines: they set tone, reveal character, heighten tension, and sometimes deliver the emotional climax. Tarantino has said: “Music is the heartbeat of my movies.” His choices are deeply personal, wildly eclectic, and always purposeful.

Here are the major musical influences that shape his filmography, with examples of how he transforms them into cinematic gold.

1. 1970s Soul, Funk & Disco

- Key Artists: Al Green, Bobby Womack, The Delfonics, Kool & the Gang, Donna Summer, Isaac Hayes

- Signature Elements: Smooth grooves, lush strings, emotional depth, sexy swagger

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Jackie Brown (1997) is practically a love letter to 1970s soul. The opening credits feature Bobby Womack’s “Across 110th Street,” setting the tone for a film about aging criminals and lost dreams.

- The Delfonics’ “Didn’t I (Blow Your Mind This Time)” plays during Pam Grier’s emotional scenes, turning a simple drive into a heartbreaking moment.

- Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together” in Pulp Fiction underscores the tenderness beneath Vincent and Mia’s dangerous flirtation.

- Growing up in Jamshedpur, where old Hindi film songs and 70s Bollywood disco tracks were always playing at weddings and family gatherings, I instantly connected with Tarantino’s soul choices. When I first heard “Across 110th Street” in Jackie Brown, it felt like the music of my parents’ generation—warm, nostalgic, a little bittersweet. Tarantino made me realize that music from the past can still feel urgent and alive.

2. Ennio Morricone & Spaghetti Western Scores

- Key Composer: Ennio Morricone (The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, Once Upon a Time in the West)

- Signature Elements: Sweeping orchestral themes, twangy guitars, eerie whistles, dramatic crescendos

- Tarantino’s Use:

- The Hateful Eight features three original Morricone pieces (his first original score since 1981), plus reused tracks from Morricone’s back catalog.

- Django Unchained uses Morricone’s “The Braying Mule” and “Ancora Qui” (sung by Elisa).

- Inglourious Basterds opens with Morricone’s “The Verdict” from The Big Gundown.

- As someone who grew up watching dubbed Italian westerns on late-night TV in Jharkhand, Morricone’s music always felt epic and otherworldly. Tarantino’s reverence for him made me appreciate how a single whistle or guitar twang can carry an entire story. It’s the same feeling I get during Durga Puja processions in Ranchi when the dhol and shehnai play—music that tells a story without words.

3. Surf Rock, Rockabilly & 1960s Pop

- Key Artists: Dick Dale (“Misirlou”), The Centurians, The Tornadoes, Nancy Sinatra, The Statler Brothers

- Signature Elements: Twangy guitars, reverb-heavy surf riffs, retro cool

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Pulp Fiction’s opening credits explode with Dick Dale’s “Misirlou”—the most iconic music cue in modern cinema.

- Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is drenched in 1960s California rock and pop (Paul Revere & the Raiders, The Mamas & the Papas, Deep Purple).

- Nancy Sinatra’s “Bang Bang” in Kill Bill is one of the most haunting uses of a pop song in any film.

- “Misirlou” was the first song I ever heard that made me understand how music could be a character. I remember playing it on repeat in my college hostel in Jamshedpur, feeling like I was in a movie. Tarantino showed me that even a 60-year-old surf track can feel dangerous and sexy in the right context.

4. Blaxploitation & Funk Soundtracks

- Key Composers/Artists: Isaac Hayes (Shaft), Curtis Mayfield (Super Fly), Roy Ayers

- Signature Elements: Wah-wah guitars, driving basslines, orchestral flourishes

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Jackie Brown features Roy Ayers’ “Exotic Dance” and “Street Life” by Randy Crawford.

- Django Unchained includes James Brown’s “The Payback” and “I Got a Name” by Jim Croce (though not strictly blaxploitation).

- The funk and soul in Tarantino’s films reminded me of the old Bollywood disco tracks my uncles loved—Bappi Lahiri, Kalyanji-Anandji. Tarantino made me see that groove and attitude are universal. That bassline can carry just as much emotion as any dialogue.

5. Classic Rock, Country & Folk

- Key Artists: The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Johnny Cash, Deep Purple, The Brothers Johnson

- Signature Elements: Raw energy, storytelling lyrics, emotional resonance

- Tarantino’s Use:

- Once Upon a Time in Hollywood is packed with 1969 rock (The Rolling Stones’ “Out of Time,” Deep Purple’s “Hush”).

- Django Unchained uses Johnny Cash’s “Ain’t No Grave” for the final scene.

- The Hateful Eight features The White Stripes’ “Apple Blossom” in the credits.

- Growing up in a family that loved old Hindi film songs and classic rock (thanks to my dad’s cassette collection), I always felt music could tell stories. Tarantino’s use of Johnny Cash in Django Unchained felt like the perfect ending to a revenge saga—dark, defiant, and deeply human.

6. Other Notable Musical Influences

- Italian Film Composers: Riz Ortolani (Cannibal Holocaust), Luis Bacalov (Django)

- Japanese Enka & City Pop: Meiko Kaji’s “The Flower of Carnage” in Kill Bill

- Latin & World Music: Santa Esmeralda’s “Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood” in Kill Bill

- Hip-Hop & Rap: Tupac, Jay-Z, and modern tracks in later films (e.g., The Weeknd in The Hateful Eight credits)

Tarantino’s soundtracks are like mixtapes from a friend who knows every corner of music history. In Jamshedpur, where we grew up listening to everything from Kishore Kumar to Metallica, his eclectic choices felt like home. He taught me that music isn’t just background—it’s the soul of the story. When I write or make videos now, I always ask: “What song would Tarantino use here?” It’s become my secret weapon.

Where to Insert This S

Criticism of Tarantino’s Filmmaking

No serious discussion of Tarantino is complete without critique. His indulgence in long dialogue scenes can feel self-absorbed. His portrayal of race and gender has sparked intense debate—some argue his films prioritize style over emotional depth. The frequent use of the N-word in Django Unchained and Jackie Brown drew both praise and condemnation. His on-screen foot shots have become a meme for a reason.

Others question whether his cinephilia crosses into fetishization—whether homage sometimes becomes dependence. And yes, his violence can feel excessive, even gratuitous.

Yet even his critics acknowledge that Tarantino is never lazy. Every flaw is a byproduct of excess, not apathy. He swings hard—and sometimes misses—but he never plays safe.

As a film lover from Jharkhand, I’ve had debates with friends about Tarantino’s use of racial slurs and gender dynamics. Some of us defend it as historical context; others feel it crosses lines. What I appreciate is that he never pretends to be neutral—he forces us to confront uncomfortable material. That provocation is part of what makes his work linger long after the credits roll.

The Ten-Film Rule: Knowing When to Leave

Tarantino’s decision to stop after ten films is as much a statement as any of his movies. He believes directors decline when they overstay their creative peak. Rather than becoming a parody of himself, he wants to leave behind a tight, intentional body of work.

This philosophy reflects discipline rarely seen in Hollywood. It’s not about scarcity—it’s about legacy.

In a world where franchises never end, Tarantino’s choice feels almost radical. Living in Jamshedpur, where we often see the same actors and directors recycling old ideas, I admire his courage to walk away at the top. It’s a reminder that sometimes the bravest thing an artist can do is stop.

Tarantino teaches us that obsession is fuel. That voice matters more than polish. That loving art deeply is not a weakness—it’s a weapon.

He reminds us that rules are optional, structure is flexible, and taste is personal.

Lessons for Aspiring Writers and Directors

- Watch everything—especially bad movies. Tarantino learned more from exploitation films than from “respectable” cinema. Bad movies teach you what not to do.

- Write dialogue that scares you. If it doesn’t make you nervous, it’s not honest.

- Embrace your weirdness. Tarantino’s foot fetish, his love of kung-fu, his encyclopedic knowledge—none of it is hidden. It’s celebrated.

- Don’t chase trends; create taste. Tarantino never followed the market—he created his own.

- Learn cinema history. You can’t break rules you don’t know.

- Make bold choices. Nonlinear narratives, long takes, extreme violence—go all in.

- Protect your voice. Tarantino has final cut on every film. Fight for your vision.

- Structure is storytelling. Use chapter breaks, flashbacks, and tone shifts to serve the theme.

- Entertainment and intelligence can coexist. You can be smart and fun at the same time.

- Know when to stop. Legacy is better than longevity.

Ten Famous Quentin Tarantino Quotes

- “When people ask me if I went to film school, I tell them, ‘No, I went to films.’”

- “I steal from every single movie ever made.”

- “Violence is one of the most fun things to watch in movies.”

- “Movies are my religion.”

- “If you just love movies enough, you can make a good one.”

- “I reject your hypothesis.”

- “I don’t believe in elitism.”

- “Cinema doesn’t have to be perfect.”

- “Genre films can be art.”

- “I want to stop at the top.”

Conclusion

Quentin Tarantino is not merely a filmmaker; he is a provocation. He challenges audiences to rethink storytelling, critics to rethink taste, and filmmakers to rethink courage. His legacy is not just a list of iconic films—it is permission. Permission to be loud, personal, excessive, and unapologetically in love with cinema.

As someone who grew up in Jharkhand watching pirated DVDs and dreaming of bigger stories, Tarantino gave me permission to love movies without apology. He showed me that passion, knowledge, and courage can turn a kid from a small city into someone who can speak about cinema with confidence. Whether history crowns him genius or provocateur, one thing is certain: modern cinema—and my own love for it—would be unrecognizable without Quentin Tarantino.

So next time you watch a Tarantino film, remember: it’s not just entertainment. It’s a conversation with cinema history, a love letter to obsession, and a reminder that sometimes the boldest thing you can do is be yourself—loudly, proudly, and without compromise.