Introduction & Context

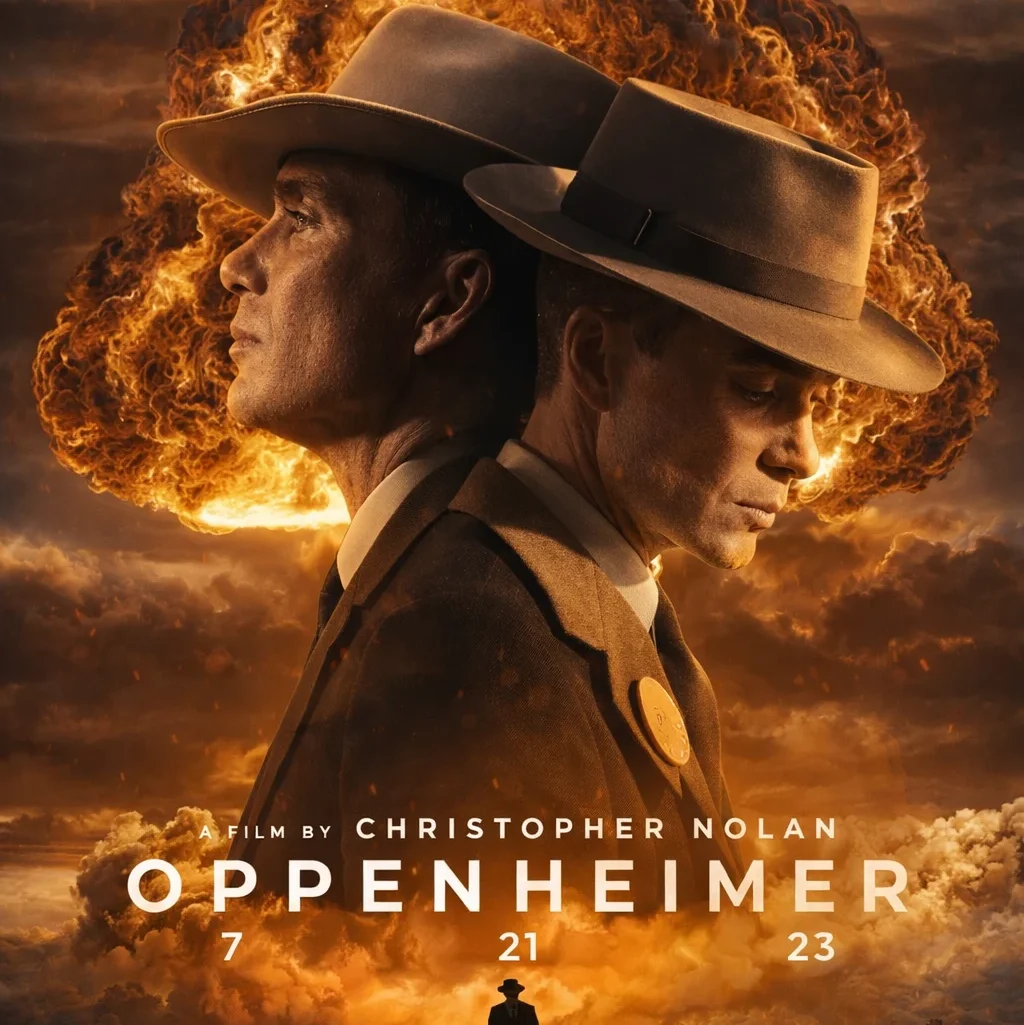

Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer (2023) is not simply a historical biopic; it is a profound cinematic inquiry into the burden of knowledge and the consequences of creation. Centered on J. Robert Oppenheimer, the brilliant theoretical physicist who led the Manhattan Project, the film interrogates the uneasy relationship between intellect and power. In doing so, Nolan resists the traditional hero’s journey and instead constructs a portrait of a man whose greatest achievement becomes his lifelong psychological imprisonment.

The film arrives at a moment when humanity is again confronting the dangers of unchecked innovation. Nuclear weapons remain a constant geopolitical threat, while emerging technologies such as artificial intelligence raise similar ethical anxieties about creators losing control over their creations. Oppenheimer therefore feels urgently contemporary despite its mid-20th-century setting. Nolan uses history not as nostalgia, but as a mirror—one that reflects modern fears about ambition, responsibility, and moral blindness.

Unlike conventional war epics that rely on battlefield spectacle, Oppenheimer unfolds largely in conference rooms, laboratories, and interrogation chambers. Dialogue, memory, and psychological tension replace action set-pieces. The Trinity Test, the film’s most anticipated moment, is not presented as triumph but as a haunting rupture in human history. Nolan deliberately strips away celebratory framing, allowing silence and dread to dominate the aftermath.

The film’s cultural impact is also significant. In an era dominated by superhero franchises and fast-paced streaming content, Oppenheimer defies expectations: a three-hour, R-rated, dialogue-heavy drama that demands patience and intellectual engagement. Its success challenges assumptions about audience attention spans and reaffirms cinema’s capacity to tackle complex moral questions at scale.

Ultimately, Oppenheimer positions itself not as a lesson in history, but as a cautionary tale. It asks a question that lingers long after the credits roll: when knowledge grants god-like power, who bears the moral cost of using it?

Why Oppenheimer Matters Today

The relevance of Oppenheimer extends far beyond its historical subject. At its core, the film grapples with the ethical consequences of technological advancement—a theme that resonates powerfully in the 21st century. Just as nuclear physics transformed warfare and global politics, modern innovations such as artificial intelligence, genetic engineering, and surveillance technologies are reshaping society in unpredictable ways. Nolan’s film serves as a reminder that progress without ethical reflection can become catastrophic.

Oppenheimer’s internal conflict mirrors a modern dilemma faced by scientists, engineers, and policymakers today: should something be created simply because it can be? The Manhattan Project was justified as a wartime necessity, yet its success introduced a permanent existential threat. Similarly, today’s technological race often prioritizes speed and dominance over responsibility. The film forces viewers to confront uncomfortable parallels between past and present decision-making.

Politically, Oppenheimer also speaks to contemporary anxieties about power structures and ideological persecution. The post-war Red Scare hearings depicted in the film reflect how fear can override justice, turning intellectuals into scapegoats. In a time when dissenting voices are frequently silenced or polarized, Nolan’s portrayal of political paranoia feels strikingly relevant.

Moreover, the film challenges modern audiences to reconsider hero worship. Rather than celebrating Oppenheimer as a flawless genius, Oppenheimer presents him as deeply flawed—brilliant yet naive, visionary yet morally uncertain. This refusal to simplify aligns with a growing cultural desire for nuanced storytelling that acknowledges complexity over myth-making.

By connecting historical events to present-day ethical debates, Oppenheimer transcends the limits of biographical cinema. It becomes a meditation on humanity’s recurring tendency to repeat its mistakes, despite possessing the knowledge to avoid them.

Narrative Structure & Storytelling

One of Oppenheimer’s most distinctive elements is its unconventional narrative structure. Nolan employs a fragmented, non-linear approach that mirrors the fractured psyche of its protagonist. The film moves fluidly between timelines, perspectives, and tones, refusing to guide the audience with clear emotional signposts. This deliberate complexity demands active engagement rather than passive consumption.

The story unfolds across three primary narrative threads: Oppenheimer’s rise as a scientist, the Manhattan Project and its moral consequences, and the political reckoning that follows. These timelines intersect and overlap, creating a mosaic of memory and accusation. Nolan uses this structure not as a stylistic gimmick, but as a thematic device—illustrating how past actions haunt the present.

A crucial storytelling choice is the contrast between subjective and objective perspectives. Much of the film is anchored in Oppenheimer’s point of view, immersing the audience in his intellectual exhilaration and growing dread. However, this subjectivity is frequently challenged by external judgments, particularly during the security clearance hearings. The shifting viewpoints force viewers to question whose version of truth they are witnessing.

Dialogue-driven scenes dominate the narrative, emphasizing ideas over events. Scientific discussions, political debates, and philosophical exchanges replace traditional action. While this approach risks alienating some viewers, it reinforces the film’s intellectual weight. The tension arises not from physical danger, but from ideological confrontation and psychological unraveling.

Nolan also withholds emotional catharsis. Even moments of success are undercut by looming consequences. The Trinity Test, though visually restrained, becomes the emotional climax—not because of spectacle, but because of what it represents. The narrative refuses resolution, ending instead on an ominous reflection about humanity’s future.

Through its layered storytelling, Oppenheimer transforms a historical account into an experiential journey through guilt, memory, and responsibility.

Direction & Nolan’s Filmmaking Choices

Christopher Nolan’s direction in Oppenheimer reflects a significant evolution in his filmmaking style. Known for large-scale spectacle and intricate plotting, Nolan here channels his ambition inward, focusing on character psychology rather than visual excess. The result is a restrained yet intensely immersive experience.

Nolan’s decision to shoot extensively in IMAX may seem paradoxical for a dialogue-heavy film, but it serves a clear purpose. The large-format visuals amplify intimacy rather than grandeur, capturing subtle facial expressions and emotional shifts. The human face becomes the battlefield, reinforcing the film’s internal conflicts.

Practical effects dominate Nolan’s approach, most notably in the depiction of the Trinity Test. By avoiding CGI, Nolan grounds the moment in physical reality, emphasizing its terrifying authenticity. The delayed sound design following the explosion creates a sense of dread that lingers, transforming a scientific milestone into a moment of existential horror.

Pacing is another bold choice. The film moves relentlessly, often overwhelming the audience with information and emotional intensity. This is intentional; Nolan mirrors Oppenheimer’s own mental overload, immersing viewers in the chaos of competing ideas and pressures. The lack of narrative breathing room reinforces the film’s oppressive atmosphere.

Perhaps Nolan’s most daring decision is his refusal to moralize overtly. He presents events without clear judgment, trusting the audience to wrestle with ethical ambiguity. This restraint elevates Oppenheimer beyond conventional historical drama, positioning it as a cinematic thought experiment rather than a definitive statement.

Through precise direction and deliberate restraint, Nolan crafts a film that challenges, unsettles, and endures—an intellectual epic that prioritizes consequence over comfort.

Performances & Character Psychology

At the emotional core of Oppenheimer lies an extraordinary set of performances that transform dense historical material into a deeply human experience. Cillian Murphy’s portrayal of J. Robert Oppenheimer is central to the film’s impact. Murphy does not play Oppenheimer as a traditional protagonist; instead, he embodies contradiction. His performance oscillates between quiet confidence and visible fragility, capturing a man who is both intellectually dominant and emotionally vulnerable.

Murphy’s physicality is crucial to the character psychology. His hollowed cheeks, restless eyes, and rigid posture convey internalized anxiety long before it is verbalized. Even in moments of professional triumph, there is an undercurrent of dread. The performance suggests that Oppenheimer understands the implications of his work earlier than he admits, making his later guilt feel inevitable rather than sudden.

Emily Blunt’s Kitty Oppenheimer adds another psychological dimension. Often sidelined in historical accounts, Kitty is portrayed here as emotionally perceptive and quietly resentful of the moral evasions around her. Blunt balances bitterness with strength, especially in moments where she confronts the hypocrisy of political persecution. Her courtroom testimony becomes a moral counterweight to Oppenheimer’s passivity.

Robert Downey Jr.’s Lewis Strauss offers a sharply contrasting psychological portrait. Where Oppenheimer is internally conflicted, Strauss is externally controlled and emotionally repressed. Downey Jr. abandons charisma in favor of restrained resentment, revealing how wounded ego and ideological rigidity can be as destructive as scientific ambition.

Supporting performances—from Matt Damon’s pragmatic General Groves to Florence Pugh’s emotionally volatile Jean Tatlock—further deepen the psychological landscape. Each character represents a different response to power: compliance, idealism, rebellion, or denial. Together, these performances elevate Oppenheimer from historical drama to psychological tragedy.

Sound, Editing & Technical Craft

Technically, Oppenheimer represents one of Christopher Nolan’s most meticulously crafted films, showcasing his ability to integrate narrative, performance, and aesthetic elements into a unified, immersive cinematic experience. The film’s technical design—encompassing sound, editing, cinematography, and production techniques—functions not merely as decoration but as an essential component of storytelling, shaping the audience’s psychological and emotional engagement at every stage. Nolan’s technical choices work in constant dialogue with the narrative, ensuring that form and content reinforce one another, and creating a cinematic world where the weight of moral and intellectual tension is felt as keenly as it is understood.

At the forefront of this technical mastery is Ludwig Göransson’s score. Unlike traditional film music that often offers emotional relief or melodious comfort, Göransson’s composition in Oppenheimer is deliberately unsettling. The music functions almost as a psychological instrument, amplifying anxiety, tension, and the relentless acceleration of events. Strings frequently pulse with nervous energy beneath otherwise calm dialogue, turning intellectual debates into moments of palpable suspense. Scenes of scientific discourse, which might otherwise appear static, are elevated into emotionally charged encounters through the interplay of sound and rhythm. Silence is employed with equal precision and impact. The moments immediately following the Trinity Test, for example, are deafening in their quietude; the absence of sound forces the audience to confront the enormity of the explosion, not just as a physical event but as a moral and existential rupture. This technique transforms silence into a vehicle for reflection and horror, a decision that underscores Nolan’s refusal to present spectacle without consequence.

Equally critical is Jennifer Lame’s editing, which is both rigorous and thematically resonant. The film employs rapid cross-cutting between multiple timelines, oscillating between Oppenheimer’s work on the Manhattan Project, his personal relationships, and the post-war security hearings. This fragmented temporal structure mirrors the fractured nature of memory and the persistent burden of guilt, reinforcing the film’s exploration of ethical and psychological complexity. The editing rarely allows for narrative or emotional rest; viewers are placed inside Oppenheimer’s mental state, experiencing the accumulation of pressure, uncertainty, and moral responsibility almost firsthand. While this approach demands concentration and patience, it is precisely this intensity that deepens engagement with the character and narrative. Editorial choices, from pacing to rhythm, are therefore not arbitrary but intimately aligned with the film’s psychological content.

Cinematography further amplifies the technical sophistication of Oppenheimer. Hoyte van Hoytema’s work subtly manipulates color, light, and framing to indicate shifts between subjective and objective perspectives. Black-and-white sequences are used selectively, often signaling retrospection, judgment, or moral scrutiny, while color scenes are grounded in immediacy and physical presence. These visual cues are more than aesthetic flourishes; they serve as a philosophical lens through which the audience navigates truth, perception, and the limits of memory. The interplay between lighting and composition often isolates characters within the frame, visually representing emotional isolation, ethical tension, or the burden of knowledge.

Practical effects are another cornerstone of Nolan’s technical strategy. The Trinity Test, arguably the film’s most iconic sequence, is rendered with a combination of practical explosions, miniature models, and carefully controlled environmental effects. By minimizing CGI, Nolan grounds the narrative in tangible reality, emphasizing the authenticity of Oppenheimer’s achievement and the terrifying scope of its consequences. Practical effects, combined with precise sound and visual design, create a sensory immersion that is both awe-inspiring and morally sobering.

Furthermore, the integration of technical elements extends to camera movement and framing. The film frequently employs long takes, close-ups, and slow tracking shots to accentuate tension, highlight emotional nuance, and reinforce the isolation of characters within their environments. Spatial composition often mirrors the psychological state of characters, using distance, scale, and perspective to convey pressure, moral conflict, and intellectual burden.

In sum, the technical craft of Oppenheimer is inseparable from its storytelling. Every aspect—Göransson’s disquieting score, Lame’s rigorous editing, van Hoytema’s expressive cinematography, and the use of practical effects—serves narrative and thematic purposes. Nolan’s meticulous attention to these elements transforms the film from a historical drama into a visceral, psychologically immersive experience. By aligning form with content, Oppenheimer demonstrates how technical mastery can elevate cinematic storytelling, allowing audiences to feel the weight of genius, moral ambiguity, and historical consequence as acutely as the characters themselves. It is a masterclass in filmmaking where craft and concept are inseparable, making the technical dimension a core pillar of the film’s enduring impact.

Ethics, Guilt & Moral Conflict

Oppenheimer places ethical responsibility not only on its characters, but also on its audience. Nolan refuses to dictate moral conclusions, instead inviting viewers to wrestle with discomfort. The film challenges the assumption that intention absolves consequence.

Oppenheimer’s guilt is portrayed as delayed and incomplete. He recognizes the horror of the atomic bomb, yet struggles to fully oppose its continued use. This ambiguity forces viewers to question whether awareness alone is sufficient. Is regret meaningful if it does not translate into resistance?

The film also interrogates collective guilt. Scientists, politicians, and military officials all share responsibility, yet accountability is unevenly distributed. Oppenheimer becomes a symbolic scapegoat, punished not for creating destruction, but for expressing unease about it. From the viewer’s perspective, this raises unsettling questions about how societies assign blame.

By refusing emotional resolution, Oppenheimer leaves audiences morally unsettled. The final moments suggest that ethical reckoning is ongoing, not confined to history. In this way, the film implicates the viewer as a participant in the same cycle of progress and denial.

Strengths, Limitations & Criticism

Among Oppenheimer’s most remarkable strengths is its unwavering intellectual ambition. In an era where mainstream cinema often prioritizes spectacle over substance, Nolan’s film dares to challenge its audience with a dense, multi-layered narrative that weaves together historical, ethical, and psychological threads. Few blockbuster films place such trust in viewers, inviting them to grapple with moral ambiguity, complex scientific ideas, and the profound consequences of human invention. The narrative is structured not merely to recount events, but to immerse audiences in the mental and emotional pressures that define Oppenheimer’s world. By blending non-linear storytelling, layered character perspectives, and philosophical interrogation, Nolan creates an experience that is as intellectually stimulating as it is emotionally resonant.

The performances are central to this cohesion. Cillian Murphy’s portrayal of Oppenheimer embodies subtlety and restraint, capturing the internal conflict of a man whose genius carries devastating consequences. Supporting actors—Emily Blunt, Robert Downey Jr., Matt Damon, and Florence Pugh—add depth and texture, representing a spectrum of human responses to power, ambition, and moral responsibility. These performances are amplified by Ludwig Göransson’s score and Jennifer Lame’s editing, which work in tandem to sustain tension and emotional engagement. The sound design, in particular, transforms ordinary dialogue into a medium of suspense, while moments of silence—such as the aftermath of the Trinity Test—heighten the gravity of Oppenheimer’s moral dilemma. Collectively, these elements forge a cohesive cinematic experience that is rare in contemporary filmmaking.

Yet these same strengths also introduce limitations. The film’s relentless pacing and heavy reliance on dialogue can prove taxing for viewers seeking traditional emotional accessibility or visually driven spectacle. At times, the dense exposition risks overwhelming the audience, demanding sustained attention and intellectual engagement. Additionally, while the female characters are portrayed with nuance and complexity, they remain largely defined by their relationships to Oppenheimer. Kitty Oppenheimer’s moral clarity, Jean Tatlock’s emotional volatility, and other supporting female roles are presented primarily through the lens of their impact on the protagonist, limiting narrative balance and sidelining broader perspectives.

Another point of critique concerns the film’s focus on the creators of the atomic bomb rather than its victims. While Nolan’s psychological approach provides a penetrating exploration of responsibility, it inevitably marginalizes the experiences of those affected by nuclear warfare, particularly in Japan. This choice reinforces a Western-centric perspective, emphasizing the ethical dilemmas of privileged scientists over the suffering of broader populations. Although this narrative focus is deliberate, it is a notable limitation, as it constrains the scope of historical engagement and ethical consideration.

Despite these shortcomings, Oppenheimer’s achievements far outweigh its limitations. Its intellectual rigor, compelling performances, and technical mastery position it as a standout work in modern cinema. By daring to tackle morally and psychologically complex subject matter in a mainstream context, the film demonstrates that audiences are capable of engaging with challenging material when it is handled thoughtfully. In the landscape of contemporary filmmaking, where spectacle often supersedes reflection, Oppenheimer stands as a testament to the potential of cinema to illuminate the human condition, provoke ethical debate, and resonate long after the credits roll. Its limitations are dwarfed by its ambition, depth, and the lasting impact it delivers to viewers willing to confront the weight of its themes.

Cultural Impact & Legacy

Oppenheimer has already secured a significant place in modern cinematic history, distinguishing itself as a rare blockbuster that balances intellectual ambition with emotional depth. Its commercial success is notable not merely for box office numbers but for what it signifies about contemporary audiences: viewers are willing to engage with challenging material when it is treated with respect and crafted with care. In an era dominated by high-concept franchises and formulaic storytelling, the film’s ability to draw large audiences to a three-hour, dialogue-driven historical drama signals a renewed appetite for cinema that rewards patience, reflection, and moral engagement. This reception underscores a broader cultural shift, demonstrating that audiences can appreciate films that demand both intellectual and emotional investment.

The film’s influence extends beyond commercial success, resonating deeply within academic and cultural circles. In academic discourse, Oppenheimer has emerged as a reference point for discussions surrounding ethics in science and technology. Its exploration of the moral responsibilities of scientists, the unintended consequences of innovation, and the tension between personal ambition and societal accountability has made it a case study across multiple disciplines. Philosophers analyze its depiction of moral ambiguity; historians examine its attention to political and social context; and scientists and ethicists debate its portrayal of responsibility in technological advancement. By bridging entertainment and scholarship, Oppenheimer demonstrates that cinema can be both a reflective cultural artifact and a catalyst for serious intellectual inquiry.

Culturally, the film resonates as a meditation on progress and human fallibility. In portraying Oppenheimer not simply as a scientific genius but as a man burdened by ethical conflict, the film contributes to a renewed skepticism of unchecked technological advancement. It highlights the persistent tension between human ingenuity and moral foresight, offering a cautionary perspective that feels strikingly relevant in an age defined by rapid innovation, artificial intelligence, and global power struggles. In this sense, Oppenheimer functions not only as a historical recounting but also as a mirror reflecting contemporary anxieties about the consequences of human ambition. The film challenges audiences to consider that scientific achievement, no matter how celebrated, is inseparable from ethical responsibility.

Within Christopher Nolan’s filmography, Oppenheimer may well be remembered as his most mature and introspective work. While Nolan has often been associated with intricate narrative puzzles, high-concept thrillers, and large-scale spectacle, Oppenheimer marks a shift toward moral exploration and psychological realism. The film is less concerned with formal experimentation or narrative gimmickry and more invested in examining the profound consequences of human action. In doing so, Nolan demonstrates a willingness to place ethical inquiry and character complexity above conventional cinematic thrills, reinforcing his stature as a filmmaker unafraid to challenge both himself and his audience.

Ultimately, Oppenheimer’s legacy is multifaceted. It reaffirms the viability of intellectually ambitious cinema in mainstream markets, sparks interdisciplinary discussion about ethics and responsibility, and deepens cultural reflection on the costs of human innovation. Its influence will likely endure, shaping conversations about the intersections of science, morality, and history for years to come. In bridging the gap between popular entertainment and philosophical inquiry, Oppenheimer cements its position as a culturally, academically, and cinematically significant work that transcends the conventions of its genre.

Conclusion & Final Verdict

Oppenheimer is not a conventional film designed primarily to entertain; it is a deeply challenging, thought-provoking, and emotionally unsettling experience. Christopher Nolan’s ambitious exploration of J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb,” transcends the boundaries of traditional historical drama or biopic. Instead, it functions as a meditation on morality, responsibility, and the weight of human intellect. From the very first scene, the film demands active engagement from its audience. It refuses the comfort of clear heroes, simple narratives, or neatly resolved arcs, opting instead for moral ambiguity and psychological complexity. This approach is both its defining strength and its challenge: viewers are confronted with the tension between scientific genius and ethical consequence, witnessing a man whose brilliance directly results in devastation yet whose intentions remain morally nuanced.

One of the film’s most striking achievements is its ability to make historical events feel viscerally immediate. Nolan’s restrained direction, meticulous practical effects, and immersive IMAX cinematography draw audiences into the emotional and intellectual world of Oppenheimer. Even monumental moments, such as the Trinity Test, are not depicted as spectacles of triumph but as profoundly terrifying events that underscore the existential consequences of scientific innovation. The film makes it impossible to separate awe from dread. This deliberate choice reflects the central thesis of Oppenheimer: human progress, when divorced from moral reflection, carries a weight that no individual—or society—can fully escape.

Performance is equally critical in communicating the film’s thematic core. Cillian Murphy’s portrayal of Oppenheimer captures the subtle oscillation between intellectual confidence and psychological vulnerability. Murphy conveys, often through expression and posture rather than speech, the burden of a man who knows the destructive potential of his creation long before anyone else does. Supporting performances, from Emily Blunt to Robert Downey Jr., enrich this psychological landscape, offering perspectives that highlight the tension between personal ambition, political pressure, and ethical responsibility. These characters collectively transform what could have been a mere historical narrative into a study of human behavior under the weight of unprecedented moral stakes.

Perhaps most daringly, Oppenheimer refuses narrative closure. The film’s final sequences offer no easy answers or moral absolution; instead, they leave viewers with the lingering weight of uncertainty. This refusal mirrors real-world ethical dilemmas surrounding technological advancement and warfare. Nolan’s narrative suggests that the consequences of creation are neither contained nor confined—they ripple outward, affecting societies, generations, and global politics in ways that cannot be fully anticipated or mitigated. By ending in ambiguity, the film mirrors the ongoing tension between innovation and responsibility, urging audiences to reflect on the role of human conscience in shaping history.

In essence, Oppenheimer is a cinematic work of rare ambition and intellectual rigor. It is a blockbuster that dares to prioritize inquiry over spectacle, moral reflection over entertainment, and ethical ambiguity over resolution. Its legacy will not be defined solely by awards, box office success, or critical acclaim, but by the conversations, debates, and unease it generates. The film challenges viewers to consider the costs of human advancement, to sit with moral complexity, and to confront the uncomfortable truth that knowledge and power are inseparable from responsibility. In doing so, Oppenheimer achieves a timeless resonance, establishing itself as a film that will be studied, debated, and felt long after the credits roll.

Is Border 2 Really a Cashgrab…….?