Avatar Through Nolan’s Lens: When Two Cinematic Worlds Collide

I’ve always been fascinated by what happens when two completely different creative worlds crash into each other. Not crossovers inside stories—but behind the camera. What if Anurag Kashyap directed Avengers: Endgame? Would Thanos still be a purple god, or would he become a morally fractured, chain-smoking figure stuck in a Delhi alley, wrestling with fate and guilt? What if David Fincher made a Disney musical? Or Satyajit Ray directed Blade Runner?

These questions are less about realism and more about imagination—about style, philosophy, and worldview. Because directors don’t just tell stories; they reshape reality itself through their lens.

And one of the most intriguing “what ifs” in modern cinema is this:

What if Christopher Nolan directed Avatar?

James Cameron’s Avatar is perhaps the most visually exuberant blockbuster ever made—overflowing with color, light, emotion, and ecological spirituality. Nolan, on the other hand, is the cinematic architect of restraint: muted palettes, fractured timelines, intellectual density, and emotional distance.

Putting Nolan in charge of Avatar isn’t just a stylistic swap. It’s a philosophical collision. A battle between wonder and realism, emotion and intellect, myth and mechanism.

So let’s imagine it seriously. Let’s dismantle Cameron’s Pandora and rebuild it brick by brick—through Nolan’s eyes.

1. A World Repainted: Color, Light, and Atmosphere

James Cameron’s Pandora is a sensory overload by design. Neon blues, radiant greens, glowing flora, bioluminescent nights—it’s a world meant to feel alive, intoxicating, and almost spiritual. Cameron wants you to fall in love with Pandora at first sight.

Christopher Nolan would not.

Nolan’s films are famously desaturated, grounded, and earthy. Part of this is practical—he has red-green color blindness—but much of it is philosophical. Nolan believes color should never distract from structure. His worlds feel weighed down by gravity, dust, and time. Think of the steel greys of The Dark Knight, the washed-out war beaches of Dunkirk, or the beige cosmic loneliness of Interstellar.

Under Nolan, Pandora wouldn’t glow—it would brood.

The lush jungles would feel darker, denser, and more oppressive. Light would struggle to penetrate the canopy. Shadows would dominate the frame. Nights wouldn’t shimmer with magical blues; they’d feel cold, alien, and unsettling. The bioluminescence—if retained at all—would be subtle, functional, almost scientific rather than mystical.

Fans often joke that “Nolan’s Pandora would be concrete grey and a desertic no man’s land.” While exaggerated, the joke captures something true: Nolan would strip Pandora of spectacle to uncover structure.

Interestingly, this isn’t entirely hypothetical. Official concept art from the upcoming Avatar sequels—particularly the so-called “Ash Village”—already leans toward Nolan territory. The art depicts a near-monochrome wasteland, blanketed in ash, drained of life and color. It’s bleak, severe, and eerily realistic. Less fairy tale, more aftermath.

That Ash Village looks less like Cameron and more like Tenet wandered into Mad Max.

In a Nolan-directed Avatar, this wouldn’t be a temporary deviation—it would be the norm.

2. Light as Truth, Not Fantasy

Cameron lights Pandora evenly, beautifully, almost romantically. Every leaf glows. Every creature is visible. The world wants to be seen.

Nolan’s lighting philosophy is the opposite.

He prefers natural contrast, harsh shadows, and imperfect illumination. He often lets darkness obscure information rather than reveal it. In Nolan’s films, what you can’t see is often as important as what you can.

So imagine Pandora lit not to enchant, but to challenge perception.

Jungle scenes would feel claustrophobic. Faces would disappear into shadow. Action wouldn’t be choreographed for clarity, but for realism. The forest would feel less like a sanctuary and more like a psychological maze.

Pandora, under Nolan, wouldn’t invite you in.

It would test whether you deserve to be there.

3. Practical Effects vs. Digital Spectacle

This is where the Nolan-Avatar thought experiment becomes most controversial.

James Cameron is the king of technological ambition. Avatar didn’t just use CGI—it redefined it. Entire ecosystems were digitally constructed. Motion capture performances were pushed to emotional extremes. Pandora exists because computers allowed it to.

Christopher Nolan, by contrast, famously avoids CGI wherever possible. He prefers practical effects, miniatures, real locations, and in-camera solutions. The rotating hallway in Inception, the real plane crash in The Dark Knight Rises, the physical sets of Interstellar—these aren’t gimmicks. They’re philosophical statements.

Nolan believes reality feels more real when it is real.

So how does that philosophy survive in a world where nearly everything is fictional?

Many fans argue it simply wouldn’t. One Reddit commenter bluntly stated that Nolan’s “refusal to work with extensive CGI makes it nearly impossible” for him to direct Avatar. Another said Nolan “detests computer effects” and would never embrace Pandora’s artificiality.

But this might be an oversimplification.

Nolan doesn’t hate CGI—he hates invisible laziness. He uses digital effects when necessary but insists they support physical reality rather than replace it.

In a Nolan-Avatar, Pandora wouldn’t be fully digital. Forests would be built as massive physical sets. Creatures might be animatronic where possible. Mountains and skies could be miniature models enhanced digitally. The goal wouldn’t be immersion through spectacle, but tangibility through texture.

Shot on IMAX film or large-format cameras, Pandora would feel heavy. Real. Lived-in.

Less theme park. More documentary.

4. Camera Movement: From Elegance to Urgency

Cameron’s camera glides. It soars. It floats. Especially in the flying sequences, the camera behaves almost like a Na’vi spirit—weightless, joyful, free.

Nolan’s camera doesn’t float.

It moves with purpose.

Often handheld, often restrained, Nolan’s cinematography feels observational, even journalistic. Battles in Dunkirk feel chaotic not because they’re flashy, but because they’re confusing. You’re not watching heroes—you’re trapped alongside them.

So imagine Pandora not as a visual symphony, but as a hostile terrain observed by an outsider.

Flying scenes wouldn’t be lyrical—they’d be terrifying. The camera might stay uncomfortably close to Jake’s face, emphasizing vertigo and fear rather than freedom. Action would feel dangerous, messy, and disorienting.

Cameron wants you to marvel.

Nolan wants you to survive.

5. A Shift in Tone: From Wonder to Weight

Perhaps the most profound change would be tonal.

Avatar, despite its violence, is fundamentally optimistic. It believes in connection, healing, and harmony with nature. Even its tragedy feels cathartic.

Nolan’s cinema is rarely optimistic.

His films are somber, introspective, and morally heavy. Characters are often emotionally distant, burdened by guilt, loss, or obsession. Hope exists—but it’s fragile, conditional, and earned through sacrifice.

A Nolan-directed Avatar would lose much of its childlike wonder.

Pandora wouldn’t feel like paradise under threat—it would feel like a moral problem waiting to be solved.

The story would skew older, darker, and more philosophical. Less about saving a beautiful world, more about questioning whether any world can truly be saved.

Think less Avatar (2009), more Interstellar meets Apocalypse Now.

6. Time, Memory, and a Fractured Narrative

Christopher Nolan is obsessed with time.

Memento runs backward.

Inception stacks time like architecture.

Interstellar stretches seconds into years.

Dunkirk unfolds across three timelines simultaneously.

A Nolan-Avatar would almost certainly abandon linear storytelling.

The film might open after Jake has already chosen Pandora—then cut backward to show how and why. Or it might intercut Jake’s human past on Earth with his Na’vi present, blurring the line between memory and identity.

Pandora’s neural network—the spiritual “connection” between all living things—would be treated less like magic and more like a temporal or psychological phenomenon. Dream-hunts, visions, and Eywa connections could function like Nolan’s dream layers: real, but unstable.

The audience wouldn’t be told what to feel.

They’d be asked to piece it together.

7. Identity as Trauma: Jake Sully Rewritten

In Cameron’s Avatar, Jake Sully’s transformation is liberating. His human body is broken; his Na’vi body is whole. The shift is emotional, physical, and ultimately empowering.

Nolan would complicate this.

Jake’s transformation would be a psychological crisis.

Fans speculate Nolan would explore cognitive dissonance: phantom-limb syndrome, dissociation, hallucinations, dysphoria. Jake might struggle to distinguish where one self ends and the other begins.

Is he becoming Na’vi—or losing himself entirely?

Nolan is fascinated by characters who don’t trust their own perception. From Leonard in Memento to Cobb in Inception, reality is always suspect. Jake’s bond with Pandora would raise unsettling questions:

- Is Eywa a benevolent force—or a system that overrides free will?

- Is Jake choosing Pandora—or being absorbed by it?

- Is his human identity something to escape, or confront?

Under Nolan, Jake wouldn’t simply “go native.”

He’d fracture.

8. Moral Ambiguity and the Collapse of Simple Villains

Cameron’s Avatar presents a clear moral divide: humans exploit; Na’vi protect. It’s effective, emotional, and deliberately straightforward.

Nolan would never allow that simplicity.

In a Nolan-Avatar, humans wouldn’t be cartoon villains. Their motivations—resource scarcity, survival, desperation—would be examined seriously. Quaritch wouldn’t just be a brute; he’d be a soldier shaped by systems larger than himself.

Even the Na’vi wouldn’t escape scrutiny.

Their collective consciousness might be portrayed as beautiful—but also unsettling. Nolan might question whether individuality can truly exist in a world so deeply interconnected.

Is harmony freedom—or conformity?

This moral greyness would leave audiences uncomfortable. There would be no easy side to root for. Only consequences.

9. A Tragic Hero, Not a Triumphant One

Nolan’s protagonists rarely “win” cleanly.

Batman becomes a scapegoat.

Cooper loses decades with his children.

Oppenheimer saves the world—and destroys himself.

Jake Sully, under Nolan, would likely follow the same path.

Fans joke that Nolan would give Jake a dead wife—and while exaggerated, it points to something real: Nolan believes pain is the engine of transformation.

Jake’s final choice might save Pandora, but cost him his certainty, his peace, or even his identity. The ending wouldn’t be celebratory—it would be contemplative, ambiguous, haunting.

The final image wouldn’t be Jake embracing his new life.

It would be Jake questioning whether any life truly belongs to him.

10. Fan Reactions: Fascination vs. Resistance

Online discussions about a Nolan-Avatar reveal a split community.

Some fans argue Nolan is the worst possible choice—too cold, too intellectual, too detached for a story built on emotion and wonder. They describe his films as “clinical” and “dour,” the complete opposite of Cameron’s warmth.

Others are curious.

They wonder what Nolan could do with Pandora’s spiritual ideas, identity themes, and interconnectedness. They imagine Eywa as a metaphysical puzzle rather than a deity. They want to see Avatar not as a fantasy—but as a philosophical experiment.

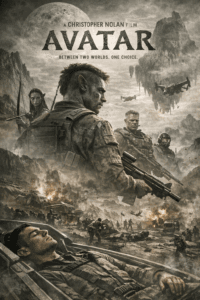

There are no full fan screenplays, but fan posters, trailers, and edits exist—often re-scoring scenes with Hans Zimmer-style music, draining the color, slowing the pace.

The consensus?

It would be divisive.

It would be strange.

And it would be unforgettable.

Conclusion: Would It Work?

Would Christopher Nolan’s Avatar be better than James Cameron’s?

Probably not.

But it would be different in the most fascinating way possible.

Cameron’s Avatar is about feeling—about immersion, empathy, and awe. Nolan’s version would be about thinking—about identity, morality, and perception.

One invites you to believe.

The other dares you to doubt.

And maybe that’s the beauty of imagining such collisions. Not because they should happen—but because they reveal how deeply a director’s worldview shapes the worlds we escape into.

Two visions.

One planet.

Completely different truths.