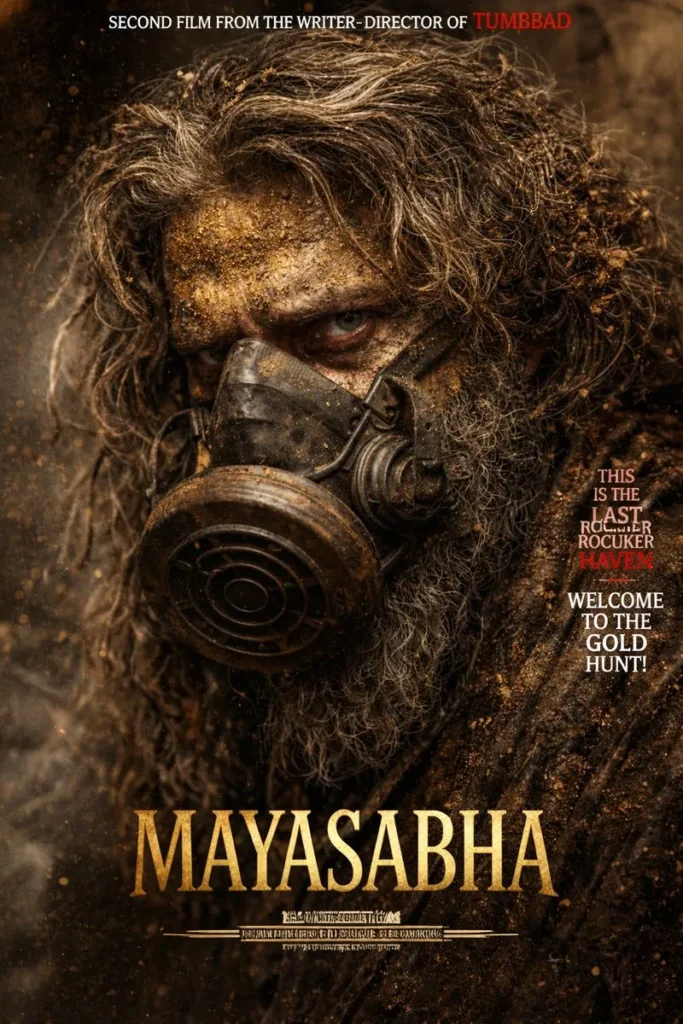

Mayasabha Review: Philosophy and Psychology

After Eight Years, Rahi Anil Barve Finally Returns with His Film

The director of Tumbbad, Rahi Anil Barve, has finally returned after eight years with his new film. While its world is different from Tumbbad, the game of greed surrounding gold continues in Mayasabha: The Hall of Illusion. After all, gold is quite expensive these days. In such a situation, a story revolving around the search for 40 kilograms of gold is bound to be intriguing.

The film manages to keep you engaged for its entire 100-minute runtime. With just four characters and a single theatre location, Mayasabha proves to be a gripping experience. If you are a lover of cinema, this is a film you should not miss.

Story

Once upon a time, Parmeshwar Khanna (played by Javed Jaffrey) was a successful film producer. Today, he lives inside his long-shut theatre, which has now become his home. His son Vasu continues to live with him, enduring his father’s anger and bitterness.

Parmeshwar hates mosquitoes, as it was during a bout of malaria that his deceitful wife made him sign over all his property to her. He constantly carries a smoke machine with him.

Vasu has a friend named Ravoraavna, and when Ravoraavna’s sister Zeenat learns that Parmeshwar has hidden 40 kilograms of gold inside the theatre, greed drives them to come there to claim it.

What happens next is worth watching—but only in the theatre.

How Is the Film?

This is a good film. More importantly, it is a different film. Watching four characters carry an entire movie on their shoulders is impressive in itself. However, if you go in expecting Tumbbad, you may feel disappointed.

This is not Tumbbad.

But it presents a fascinating world that exists within the middle of a city—one that draws you in. There are logical gaps. Many questions arise in the mind; some are answered, others are not. Parmeshwar’s riddle-speaking scenes are entertaining, and the truth behind his character is surprising.

The cinematography is top-notch. This is definitely a film of a different kind, and if you love cinema, you should watch it.

Acting

Javed Jaffrey truly displays the magic of his acting. He proves that he cannot be confined to a single box. His character has multiple layers, and he surprises you repeatedly. This could easily be considered one of the best performances of his career.

Mohammad Samad’s role feels somewhat incomplete, but within its limited scope, he does a decent job.

In a negative role, Veena Jamkar proves that she deserves more opportunities in Hindi cinema.

Deepak Damle performs according to the demands of the script, though one might expect more from him.

Direction and Writing

Rahi Anil Barve is known for his writing and his ability to create dark worlds, and he does the same here. He has written the story, screenplay, and dialogues himself, which shows how clear he was about what he wanted from his film. That clarity is why the film never feels unnecessarily stretched.

Every frame reflects Rahi’s hard work. However, in the pursuit of creativity, he sometimes forgets logic in places. Despite this, his effort is commendable. The freshness that the box office is currently searching for can be found in this film.

Art Direction

This deserves a special mention because it is one of the film’s strongest aspects. Parmeshwar’s theatre almost becomes a character in itself. The art department has designed it so thoughtfully that many times your eyes drift away from the actors to the objects placed within the space.

The background score is also effective.

Background and Context

Returning to the Illusion

Eight years is a long time to wait for a filmmaker.

Eight years is long enough for expectations to rot, mutate, and harden into myths of their own. When Rahi Anil Barve finally returned after Tumbbad, I realized I wasn’t waiting for a film anymore — I was waiting for a feeling. That strange, sinking feeling Tumbbad left behind. The sense that cinema had reached into something older than genre, older than plot.

Mayasabha: The Hall of Illusion does not give you that same feeling.

And that is the first truth one must accept.

This is not Tumbbad.

But it is unmistakably a film made by someone who understands how rot works.

A Different World, the Same Hunger

If Tumbbad unfolded in rain-soaked villages and mythic time, Mayasabha traps itself inside a decaying theatre in the middle of a city. No folklore gods. No ancient curses. Just four characters, a closed space, and a rumor heavy enough to poison everyone inside it: forty kilograms of gold.

Gold again.

It would be easy — lazy, even — to say that Rahi Anil Barve is obsessed with gold. But that would miss the point entirely. Gold, in his cinema, is not wealth. It is gravity. A force that bends morality, compresses time, and reveals who people truly are when the air gets thin.

What Mayasabha does differently is scale. Instead of generational greed, we get immediate desperation. Instead of mythic inheritance, we get rumor and opportunity. The hunger is smaller, sharper, more intimate — and therefore more uncomfortable.

You’re not watching legends destroy themselves.

You’re watching ordinary people negotiate how much dirt they’re willing to swallow.

The Theatre as a Living Body

The most important character in Mayasabha is not Parmeshwar Khanna.

It is not Vasu.

It is not Zeenat or Ravoraavna.

It is the theatre.

A closed cinema hall turned into a home, a bunker, a vault, a mausoleum. It breathes. It remembers. It judges quietly. The art direction is so deliberate that at times, human beings feel like temporary occupants inside a far older organism.

I found myself staring at objects — chairs, doors, walls, machines — longer than faces. That’s not accidental. The theatre is a museum of abandoned dreams. A place built for spectacle, now reduced to survival.

And somewhere inside this carcass of cinema, gold is rumored to be hidden.

There’s something painfully meta about that.

A filmmaker hiding a story about greed inside a dead theatre — asking us to watch it inside living ones.

Parmeshwar Khanna: A Man Who Refused to Exit

Javed Jaffrey’s Parmeshwar Khanna is one of the strangest protagonists Hindi cinema has given us in recent years.

A failed producer.

A betrayed husband.

A bitter, riddling tyrant.

A man who lives inside smoke.

He is not written to be likable. He is not written to be sympathetic. And yet, you cannot look away from him. Jaffrey plays him like a man whose anger has aged into routine. This isn’t rage anymore. This is habitual cruelty.

His hatred of mosquitoes is not comic eccentricity — it’s psychological residue. Malaria didn’t just make him sick; it robbed him of agency. The disease coincided with betrayal, and now every insect becomes a reminder that the smallest forces can ruin a life.

The smoke machine he carries isn’t just protection. It’s control. He controls the air. He controls breath. Inside the theatre, Parmeshwar decides what is visible and what is suffocating.

That’s not madness.

That’s power, reduced to its most primitive form.

The Psychology of Staying

One question haunted me throughout the film:

Why does anyone stay?

Vasu stays.

Ravoraavna stays.

Zeenat enters knowing the danger — and stays.

The obvious answer is gold. But Mayasabha is smarter than that. Gold explains entry, not endurance.

People stay because the rules are unclear but consistent. Because chaos, once understood, becomes manageable. Because leaving means returning to a world where failure is already written.

The theatre offers something strange: a closed system. No outside judgment. No larger consequences — at least, not immediately.

Psychologically, that is seductive.

The film doesn’t dramatize this. It lets it unfold naturally. Arguments fade into routines. Threats become background noise. Even fear settles into familiarity.

And that’s when the real horror begins.

Why the Film Feels Uncomfortable, Not Scary

Mayasabha is often described as dark or eerie, but I don’t think it’s frightening in the traditional sense.

There are no jump scares.

No monsters.

No sudden violence meant to shock.

Instead, the discomfort comes from recognition.

The film understands that modern horror isn’t about what attacks us — it’s about what we slowly agree to live with. Compromises don’t announce themselves. They seep in.

By the halfway point, I realized I wasn’t waiting for escape anymore. I was curious about how they would coexist inside the mess. That curiosity disturbed me.

Because it meant the film had already worked on me.

Cinematography: Letting the Air Rot

Visually, Mayasabha is restrained, controlled, almost stubbornly unflashy. The camera doesn’t romanticize decay, but it also doesn’t rush past it. Lighting is functional, sickly, often dim — like the world itself is tired.

What’s remarkable is how the film avoids visual relief. Even moments that could have been framed beautifully are kept grounded, claustrophobic.

This is not aesthetic misery.

This is environmental pressure.

By refusing beauty, the film makes you adapt — just like the characters do.

And slowly, against your will, the mess begins to make sense.

The First Shift Inside Me

Somewhere during the film, I stopped hoping for logic to rescue me.

I stopped asking why certain decisions were made. I stopped demanding explanations. I began accepting the film’s internal reality.

That was the moment I realized Mayasabha wasn’t testing its characters.

It was testing me.

How long before I stop resisting ambiguity?

How long before discomfort becomes texture?

How long before I start calling survival “strategy”?

What This Film Asks of You

Mayasabha does not ask for your approval.

It does not ask for your sympathy.

It asks for your patience.

Patience to sit with unanswered questions.

Patience to accept flawed logic.

Patience to remain inside a space that doesn’t care about your comfort.

If you give it that patience, the film does something rare.

It doesn’t impress you.

It implicates you.

Plot Overview

The Sabha, Silence, and Shared Guilt

If the first part of Mayasabha is about entering a space, the second part is about understanding why that space exists at all.

Because a sabha is never just a room.

A sabha is an agreement.

What a Sabha Really Is

In Indian cultural memory, a sabha is supposed to be orderly — a place of discourse, judgment, and collective decision-making. It carries the weight of councils, courts, royal assemblies, and even democratic promise.

Mayasabha turns this idea inside out.

Here, the sabha is not where truth is spoken.

It is where truth is postponed.

No one inside the theatre openly lies. Instead, they speak in fragments, riddles, half-truths. The film makes it clear that deception doesn’t require falsehood — it only requires incompletion.

What disturbed me was how natural this felt. There was no moment where the sabha formed. No ritual, no declaration. It simply happened, as these things always do.

People stayed long enough.

They stopped objecting.

They adjusted their language.

And suddenly, a system existed.

Silence as the Most Powerful Character

The loudest thing in Mayasabha is what isn’t said.

Long pauses. Unfinished sentences. Characters choosing not to react. The film weaponizes silence not as suspense, but as participation.

Silence here isn’t fear.

It isn’t confusion.

It’s strategy.

Speaking invites consequences. Silence allows survival.

The more I watched, the more I realized: every character understands this rule instinctively. Even conflict is carefully measured. Outbursts happen only when power dynamics are secure.

This mirrors real assemblies, real institutions, real families. We learn quickly when speech is dangerous — and how much can be achieved by simply not interrupting.

The sabha thrives not on cruelty, but on restraint.

Why the Film Feels Political Without Saying Anything Political

Many will read Mayasabha as a political allegory. And they won’t be wrong.

But the film refuses banners, ideologies, and explicit references. It operates at a deeper level — one that feels almost uncomfortable to name.

This is a film about how systems maintain themselves.

Not through force.

Not through spectacle.

But through repetition and exhaustion.

No character believes the system is just. They simply believe it is inevitable. That belief is what sustains it.

The brilliance of the film lies in how it shows power as mundane. Authority is exercised through routines, not declarations. Control exists in who decides when to speak, when to move, when to breathe.

By avoiding explicit politics, Mayasabha becomes universal. You can place this sabha anywhere — a corporation, a family, a bureaucracy, a nation.

That’s why it lingers.

Collective Guilt: When Responsibility Disappears

One of the most chilling ideas in Mayasabha is how responsibility dissolves when shared.

No single character commits an unforgivable act alone. Every moral transgression is fragmented — one person enables, another benefits, another remains silent.

By the time damage is done, guilt has no owner.

This is not accidental writing. It reflects a psychological truth: shared guilt feels lighter. It is easier to live with, easier to justify, easier to forget.

I caught myself doing it while watching — mentally distributing blame so no one character felt entirely culpable.

That realization was deeply unsettling.

Because it meant I was already thinking like the sabha.

Parmeshwar’s Riddles: Power Disguised as Wisdom

Parmeshwar Khanna’s habit of speaking in riddles is often played for dark humor, but it serves a deeper function.

Riddles create hierarchy.

The one who asks the riddle controls the conversation. Others are forced into interpretation, speculation, and performance. Understanding becomes a currency — and confusion becomes obedience.

Parmeshwar doesn’t speak plainly because plain speech invites challenge. Riddles, on the other hand, create mystique. They allow him to retreat into ambiguity whenever convenient.

This is how authority often survives past relevance — by becoming symbolic rather than practical.

The film understands this. And it lets Parmeshwar remain powerful not because he is strong, but because no one is willing to strip away his language.

Why Viewers Disagree About This Film

I’ve noticed something interesting in conversations about Mayasabha.

People don’t argue about the plot.

They argue about meaning.

Some see it as a thriller.

Others see it as social commentary.

Some dismiss it as illogical.

Others defend its ambiguity passionately.

This isn’t confusion. It’s design.

Mayasabha behaves like a psychological test. What you find lacking says more about your expectations than the film itself. Those who demand clarity see gaps. Those comfortable with uncertainty see layers.

The film refuses to guide interpretation because guidance itself would be another form of authority.

It hands you the room and watches what you do inside it.

When I Stopped Expecting Answers

About two-thirds into the film, I gave up on resolution.

I stopped waiting for explanations, backstories, justifications. And in that surrender, something shifted.

The film became easier to watch.

Not because it improved — but because I adapted.

This realization haunted me long after.

Because adaptation is not acceptance.

And comfort is not innocence.

The Sabha as a Mirror

By the end of this section of the film, it became clear to me that the sabha wasn’t meant to be feared.

It was meant to be recognized.

We have all sat in rooms where silence felt safer than honesty.

We have all benefited from systems we criticize.

We have all stayed longer than we should have.

Mayasabha doesn’t accuse us of corruption.

It accuses us of participation.

Power, Illusion, Morality

At the heart of Mayasabha lies the theme of illusion as a political tool. The enchanted hall is not merely a visual spectacle; it represents how easily human perception can be guided, distorted, and weaponized. Those who control appearances gain an advantage over those who trust only their senses. The film suggests that power in such a world does not always come from strength or righteousness but from the ability to define what others believe to be real.

Closely tied to this is the idea of pride and vulnerability. Characters who enter the court with rigid self-confidence are often the ones most easily shaken. Their humiliation is not caused by direct attack but by their own assumptions. In this way, the film presents ego as a weakness that illusion can expose. Power, therefore, is shown to be unstable when built purely on status and image.

Another major theme is the conflict between strategy and ethics. Some characters view the deceptive nature of the Mayasabha as a clever, bloodless way to defeat enemies without war. Others see it as a dangerous moral compromise that replaces honor with trickery. This tension raises an important question: is manipulation justified if it prevents violence, or does it inevitably plant the seeds of a greater conflict later?

The film also explores perception versus truth. Events inside the hall are interpreted differently by each witness, and those interpretations shape political reality more than the actual facts. Rumor, exaggeration, and wounded pride transform small incidents into historic turning points. Through this, Mayasabha argues that truth in politics is often less powerful than the story people choose to believe.

Finally, there is the theme of inevitability. Once illusion is used to shift the balance of power, it cannot be undone. Even if intentions were partly noble, the consequences move beyond anyone’s control. The film portrays history as something that can be nudged by a single symbolic act, after which events accelerate toward outcomes no one originally intended.

Characters and Performances

Maya, Myth, and the Seduction of Decay

By the time Mayasabha reaches its later movements, it no longer feels like a film that is progressing forward. It feels like a film that is sinking deeper.

Not deeper into plot.

Deeper into state of mind.

And this is where the word Maya begins to matter—not as a title, but as a philosophy.

Maya Is Not a Lie. It Is a Habit.

In popular understanding, Maya is often reduced to “illusion,” as if it were something external, something imposed upon us. But Indian philosophy has always treated Maya as more intimate than that.

Maya is not the lie we are told.

Maya is the lie we learn to live inside.

Mayasabha understands this distinction profoundly.

No character is tricked into believing something false. Everyone knows the air is polluted. Everyone knows the gold is dangerous. Everyone knows trust is compromised.

And yet, they proceed.

That is Maya—not deception, but continuation.

The illusion isn’t that everything is fine. The illusion is that this is manageable. That poison can be filtered. That systems can be navigated without being internalized.

Watching this unfold, I realized how rarely cinema portrays illusion this way. Most films expose lies dramatically. Mayasabha shows something quieter: how truth loses urgency when survival depends on ignoring it.

Myth Without Gods

One of the strangest things about Mayasabha is how mythic it feels without invoking mythology directly.

There are no gods.

No curses.

No prophecies.

And yet, the structure of the film is unmistakably mythic.

Time feels circular. Decisions echo each other. Characters repeat patterns they believe they are choosing freely. The theatre becomes less a location and more a realm—a bounded universe with its own rules, rewards, and punishments.

In myths, people are trapped by fate or divine games. In Mayasabha, people are trapped by consent.

They enter willingly.

They stay rationally.

They adjust gradually.

This is perhaps the film’s most devastating insight: modern myths don’t need gods. They only need incentives.

Gold as a Spiritual Corruptor

Gold in Mayasabha does not glitter.

It weighs.

It is never framed as divine, aspirational, or beautiful. It exists as rumor, as pressure, as possibility. Its presence is felt more than seen, which makes it more powerful.

Spiritually speaking, gold here functions like temptation without promise. It doesn’t guarantee happiness. It only guarantees continuation inside the sabha.

In that sense, gold becomes a test not of morality, but of clarity.

Who is willing to see clearly enough to walk away?

And who convinces themselves that staying is wisdom?

When Filth Stops Being Repulsive

There is a moment—quiet, almost invisible—when the film’s environment stops feeling hostile.

The grime on the walls stops screaming for attention.

The smoke stops feeling aggressive.

The darkness stops feeling threatening.

Instead, it becomes texture.

This is one of the most psychologically accurate things Mayasabha does. Humans don’t become comfortable with decay because they love it. They become comfortable because familiarity feels safer than uncertainty.

I noticed my eyes adapting. I stopped searching for light. I stopped craving clean frames. I accepted the visual language of the film as normal.

And that realization unsettled me more than any narrative twist.

Because if filth can become normal on screen, it can become normal anywhere.

The Aesthetics of Survival

At some point, Mayasabha crosses a dangerous line.

It becomes… compelling to look at.

Not beautiful in a conventional sense, but coherent. The decay makes sense. The mess has structure. The theatre feels lived-in, intentional, almost curated.

This is where survival aesthetics emerge.

When environments are hostile long enough, humans don’t seek purity. They seek patterns. And patterns, once recognized, become comforting.

The film doesn’t glamorize this. It simply observes it.

And by observing it without comment, it forces us to confront how often we confuse adaptation with intelligence.

The Moment It Became Personal

There was a moment, late in the film, when I stopped thinking about the characters entirely.

I started thinking about rooms I have been in.

Rooms where speaking felt inconvenient.

Rooms where silence felt professional.

Rooms where staying felt easier than questioning.

The film wasn’t reminding me of corruption. It was reminding me of adjustment.

Of the times I’ve told myself, “This is just how things work.”

Of the moments when discomfort faded not because it was resolved, but because it was absorbed.

That’s when I realized Mayasabha isn’t asking whether people are good or bad.

It’s asking something far more dangerous:

How long does it take for compromise to feel like identity?

Different Viewers, Different Films

The more I reflected on Mayasabha, the more I understood why people walk away with radically different interpretations.

Some feel it lacks logic.

Some feel it lacks resolution.

Some feel it lacks emotional payoff.

Others feel haunted.

Disturbed.

Exposed.

This is because the film does not meet the viewer halfway. It demands that you bring your own tolerance for ambiguity, your own relationship with systems, your own history with compromise.

Those who expect cinema to deliver meaning feel frustrated.

Those who allow cinema to reveal meaning feel unsettled.

Neither reaction is wrong.

But they say very different things about us.

Maya as Addiction

The most disturbing thought I had after watching Mayasabha was this:

What if Maya isn’t something we want to escape?

What if Maya is something we return to because clarity is exhausting?

The film suggests that illusion offers structure. It tells you where to stand, when to speak, how much to hope. Truth, on the other hand, demands action—and action demands risk.

Inside the sabha, the rules are cruel but consistent.

Outside, the world is uncertain.

For many, that trade-off feels reasonable.

Why the Film Refuses Redemption

There is no cleansing moment in Mayasabha.

No moral awakening.

No final stand.

And that’s not cynicism. It’s honesty.

Redemption implies recognition followed by change. But most systems do not collapse because they are exposed. They collapse only when they are abandoned.

Mayasabha shows us recognition without abandonment.

And that, perhaps, is the most truthful ending it could offer.

What Stayed With Me

Long after the film ended, what stayed with me wasn’t fear or anger.

It was familiarity.

The uncomfortable realization that nothing in the film felt alien. The sabha didn’t feel fictional. The silence didn’t feel exaggerated. The decay didn’t feel symbolic.

It felt… observed.

As if the film had quietly taken notes on how we live—and played them back without commentary.

Direction and Visual Storytelling

The direction of Mayasabha relies heavily on visual contrast to communicate meaning. Wide, symmetrical shots of the grand hall create a sense of order and perfection, while sudden shifts to tilted or obstructed angles mirror the characters’ confusion. The camera often lingers on reflections and mirrored surfaces, reminding the viewer that every image might be deceptive.

Lighting plays a crucial symbolic role. Bright, almost divine illumination highlights moments of political display, making rulers appear larger than life. In private conversations, however, shadows dominate, suggesting uncertainty and hidden motives. This visual shift between spectacle and secrecy reinforces the film’s central tension between public image and private intention.

The set design turns architecture into narrative. Floors that look like water, doors that seem farther than they are, and endless corridors that subtly change shape create a feeling that the environment itself is testing those who walk through it. Rather than relying on obvious magical effects, the film uses precise framing and movement to let the audience experience the same disorientation as the characters.

Transitions between scenes are often built around visual metaphors. A ripple across a reflective surface cuts to political unrest outside the palace, linking illusion inside the hall to real consequences in the wider world. Slow tracking shots during moments of tension make the space feel alive, as if the court is quietly observing and judging every visitor.

Overall, the director treats the Mayasabha not just as a backdrop but as an active participant in the story. By blending grandeur with subtle unease, the visual storytelling constantly reminds the viewer that beauty and danger can occupy the same space.

Music, Sound and Editing

The sound design of Mayasabha plays a subtle but powerful role in shaping the viewer’s emotional experience. Rather than overwhelming the audience with constant background music, the film carefully alternates between rich orchestral themes and moments of near silence. When characters first enter the enchanted hall, the music rises in layered, echoing tones that create a sense of awe and divine grandeur. The score seems to stretch the space, making the court feel larger and more mysterious than what is visible on screen.

In contrast, during tense personal exchanges, the music often fades away completely. Footsteps, fabric movement, and distant echoes become sharply audible. This quietness forces attention onto small gestures and unspoken reactions, highlighting how fragile the situation truly is beneath the surface spectacle. Silence here is not emptiness; it is pressure.

Recurring musical motifs are associated with different ideas rather than specific characters. A shimmering, almost hypnotic melody accompanies moments of illusion and visual trickery, while a heavier, steady rhythm appears when political decisions are being made. As the story progresses, these motifs begin to overlap, symbolizing how deception and governance become inseparable.

Editing is equally deliberate. Early scenes use longer takes that allow the audience to absorb the grandeur of the hall. As tensions rise, cuts become quicker and more frequent, mirroring the growing instability between factions. Reaction shots are carefully placed to capture silent humiliation, suspicion, or satisfaction, often saying more than dialogue could.

Transitions between the magical interior and the grounded exterior world are particularly striking. The edit might move from a glittering reflection inside the court to a harsh, dusty landscape outside, emphasizing the gap between illusion and reality. This rhythmic contrast keeps the viewer aware that every elegant moment inside the Mayasabha carries consequences beyond its walls.

Together, music and editing guide the audience through wonder, discomfort, and dread, turning the film’s visual illusions into a fully immersive psychological experience.

Social and Cultural Impact

Although set in a mythic or historical world, Mayasabha speaks strongly to modern audiences. Its portrayal of power built on spectacle and perception reflects contemporary societies shaped by media, image management, and narrative control. Viewers can easily recognize parallels with political theatre, public relations, and the crafting of carefully staged appearances to influence public opinion.

The film encourages debate about the ethics of psychological victory. Some may see the enchanted court as a brilliant, nonviolent strategy that avoids bloodshed. Others may argue that humiliation and deception are forms of violence in themselves, capable of igniting deeper and longer-lasting conflict. This moral ambiguity gives the story lasting relevance beyond its fictional setting.

Culturally, the use of epic-inspired mythology reconnects audiences with traditional storytelling while presenting it through modern cinematic language. It demonstrates how ancient symbols can still comment on present-day struggles for authority, dignity, and justice. For many viewers, the Mayasabha becomes a metaphor for any system that dazzles people into compliance while quietly shaping their beliefs.

The film’s reception is likely to inspire discussions about leadership styles: whether true strength lies in transparent fairness or in clever dominance. By refusing to provide a simple moral answer, it invites audiences to examine their own tolerance for manipulation when it serves stability or progress.

In this way, Mayasabha functions not only as entertainment but as a cultural mirror, reflecting how easily societies can be guided by appearances when critical awareness fades.

After the Illusion, Before the Exit

Some films end with answers.

Some end with outrage.

Mayasabha ends with something far more unsettling: continuation.

When the screen went dark, I didn’t feel released. I felt quietly returned — back to a world that suddenly looked a little too familiar.

Why Mayasabha Will Age Uncomfortably Well

Most films are products of their time. Mayasabha feels like a diagnosis of a pattern.

It will age well not because it predicts the future, but because it understands how humans behave when systems stop pretending to be fair. The film is not concerned with collapse. It is interested in what happens before collapse — the long middle phase where people adjust, normalize, and survive.

That phase doesn’t belong to any single decade.

As long as institutions exist, as long as power circulates quietly, as long as people choose convenience over clarity, Mayasabha will remain relevant.

It doesn’t depend on context.

It depends on human behavior.

Why Comparing It to Tumbbad Is Both Natural and Unfair

The shadow of Tumbbad hangs heavily over Mayasabha, and understandably so. Both films are about greed. Both use gold as a gravitational force. Both explore moral decay.

But the comparison ends there.

Tumbbad externalized greed through myth. It warned us through spectacle. It used horror as a language of excess — rain, blood, monsters, inheritance.

Mayasabha removes spectacle entirely.

There are no monsters here because the monster has already won. There is no curse because no one believes in innocence anymore. There is no inheritance because the rot is immediate.

If Tumbbad was about what greed creates, Mayasabha is about what greed maintains.

And that makes it harder to love.

The Director’s Most Ruthless Decision

Rahi Anil Barve’s boldest choice in Mayasabha is restraint.

He could have explained more.

He could have dramatized more.

He could have justified more.

He does none of that.

Instead, he trusts the audience to sit with discomfort without reward. That is a rare confidence — and a quiet cruelty. Because not everyone wants to be trusted that way. Some viewers want cinema to guide them, reassure them, tell them where to stand.

Mayasabha refuses that comfort.

It doesn’t care if you like it.

It cares if you stay.

Logic, or the Lack of It

Yes, the film has logical gaps.

Yes, some actions feel under-explained.

Yes, questions remain unanswered.

But over time, I realized something important: logic isn’t missing. It’s irrelevant.

The film isn’t simulating a fair world. It’s simulating a functioning one. And real systems are rarely logical — they are habitual.

Things don’t happen because they make sense.

They happen because they’ve happened before.

Once I stopped demanding logic and started observing behavior, the film became disturbingly coherent.

The Theatre as a Tomb and a Womb

By the end of the film, the theatre no longer felt like a location. It felt like a state of existence.

A place where cinema once promised dreams, now housing compromise.

A structure built for collective imagination, now sheltering collective denial.

There’s something painfully poetic about that.

A dead cinema hall holding a story about people who can’t leave.

It’s hard not to read that as commentary on the industry, on audiences, on all of us who still gather in dark rooms hoping to be changed without being challenged.

What the Film Ultimately Refuses to Do

Mayasabha refuses to tell you what to think.

It refuses to assign heroes.

It refuses to cleanse its world.

And most importantly, it refuses to pretend that awareness is enough.

Watching the film doesn’t absolve you.

Understanding it doesn’t redeem you.

Liking it doesn’t place you outside it.

The sabha doesn’t end because you noticed it.

It ends only when participation stops.

My Personal Exit (Which Isn’t One)

I don’t believe films change people overnight. That’s another comforting illusion.

But Mayasabha sharpened something in me — a hesitation before silence, a suspicion of comfort, an awareness of how easily adaptation masquerades as intelligence.

It didn’t make me hopeful.

It didn’t make me cynical.

It made me alert.

And perhaps that’s the highest ambition this film has.

Final Thought

If Mayasabha can be accused of anything, it’s this:

It refuses to lie to the viewer.

It doesn’t promise escape.

It doesn’t promise justice.

It doesn’t promise clarity.

It only promises recognition.

And once you recognize the sabha — in the film, in society, in yourself — you can never fully pretend you’re not sitting inside it.

That recognition is not comforting.

Conclusion

In the end, Mayasabha stands as more than a story about political rivalry or royal spectacle; it becomes a meditation on how human beings see, believe, and react to the worlds constructed around them. The enchanted hall at the center of the film is not simply an architectural wonder. It is a psychological landscape where certainty dissolves, pride is tested, and perception itself becomes a battlefield. By placing its characters inside a space designed to confuse the senses, the narrative exposes how fragile authority can be when it depends on image rather than understanding.

What makes the film powerful is not the scale of its setting but the intimacy of its insights. Each stumble on an illusory floor, each hesitant step across what appears to be water, reveals something deeply human: our need to feel in control of our surroundings. When that control is taken away, even briefly, the response is rarely calm reflection. Instead, it is embarrassment, anger, defensiveness, or denial. The Mayasabha does not defeat its visitors through violence; it unsettles them by turning their own minds against them. In doing so, the film suggests that the most effective form of dominance is often psychological.

From a philosophical perspective, the story questions the nature of truth in a world shaped by appearances. If reality can be staged convincingly enough, does it matter whether it is genuine? The rulers within the film understand that belief is more powerful than fact. A carefully crafted illusion can change reputations, shift alliances, and alter the course of history without a single weapon being raised. This idea resonates far beyond the mythical court. In every era, those who control symbols, narratives, and images hold a unique kind of power. The film quietly argues that empires of the mind can be as consequential as empires of land.

Yet Mayasabha does not celebrate this mastery of perception without hesitation. Running beneath the spectacle is a current of moral unease. The very brilliance of the enchanted court carries a hidden danger: humiliation breeds resentment. What begins as a clever display risks becoming a wound that never heals. The psychological victory achieved through illusion plants the seeds of future conflict. In this way, the film presents a paradox. Deception may offer short-term advantage, but it destabilizes the trust required for lasting peace. Power gained by unsettling others also unsettles the world that holds that power.

Psychologically, the characters embody different responses to uncertainty. Some adapt quickly, treating the illusions as puzzles to be solved. Others experience them as personal attacks, their wounded pride transforming confusion into hostility. These reactions feel authentic because they mirror real human behavior. When people are made to feel foolish or exposed, they rarely blame the circumstances alone; they search for an enemy. The film shows how easily misunderstanding becomes accusation and how quickly perception hardens into belief. In the reflective surfaces of the Mayasabha, characters see not just distorted images but distorted versions of one another.

The enchanted hall itself functions like a collective mind. Its shifting perspectives and deceptive depths resemble the inner workings of thought, where assumptions guide interpretation and expectations shape experience. Just as a visitor mistakes water for stone, people in positions of power often mistake certainty for truth. The film’s visual language turns architecture into philosophy, suggesting that reality is always filtered through perception. To walk through the Mayasabha is to walk through the limits of one’s own awareness.

Importantly, the narrative never claims that illusion alone determines destiny. Choices still matter. Advisors who urge caution represent the voice of ethical reflection, reminding rulers that brilliance without empathy is dangerous. Mediators who seek peace show that conflict is not inevitable, only increasingly likely when pride replaces humility. These figures ground the film’s grand themes in human responsibility. Illusion may create the spark, but it is the decision to nurture anger that lights the fire.

The social message that emerges is both ancient and modern. Societies are held together not just by laws or armies but by shared trust in what is real. When that trust is manipulated for strategic gain, the immediate result may be stability or admiration, but the long-term effect is doubt. Doubt erodes unity. The Mayasabha, in all its beauty, becomes a symbol of this tension. It is a masterpiece of imagination and a warning about the consequences of using imagination as a weapon.

By the final moments, the audience understands that the true conflict is not between rival rulers but between truth and appearance. The hall of illusions has revealed hidden weaknesses and ambitions, but it has also exposed the cost of such revelation. Once perception has been shaken, it cannot be restored to innocence. Relationships change, intentions are questioned, and every gesture carries suspicion. The magic of the court is therefore double-edged: it enlightens and endangers at the same time.

What lingers after the story ends is a quiet, unsettling realization. The greatest structures of power are not built from stone or gold but from belief. To alter belief is to alter reality itself. Yet belief built on deception is unstable, forever vulnerable to the moment when the illusion breaks. Mayasabha invites viewers to look beyond spectacle and ask what foundations their own certainties rest upon. Are they grounded in understanding, or merely in convincing appearances?

In philosophical terms, the film reminds us that perception is not passive. It is shaped, guided, and sometimes engineered. In psychological terms, it shows how identity and dignity are deeply tied to how we believe others see us. When that image is disrupted, the response can redefine history. The enchanted court therefore becomes a metaphor for every environment where appearances are carefully staged to influence thought.

Ultimately, Mayasabha endures because it refuses simple answers. It does not condemn intelligence or creativity, nor does it praise brute honesty without strategy. Instead, it explores the delicate balance between wisdom and manipulation, between brilliance and humility. Power, the film suggests, is safest when it understands the minds it seeks to lead rather than merely dazzling them.

The lasting image of the Mayasabha is not just of glittering floors and mirrored halls, but of people pausing mid-step, uncertain of what lies beneath their feet. That moment of hesitation captures the essence of the film. It is the instant when certainty gives way to awareness, when the familiar becomes strange, and when the viewer realizes that reality itself can be staged. In that pause lies the film’s deepest insight: that to see clearly, one must first question what seems obvious.

Through its fusion of philosophy and psychology, spectacle and introspection, Mayasabha transforms a mythical court into a study of the human mind. It leaves us with a timeless warning and an enduring question: if our worlds can be shaped by illusion, what responsibility do we bear in choosing what to believe?

Taxi driver a movie worth watching

Badhiya