THE CITY & ALIENATION — URBAN REALISM AS PSYCHOLOGICAL LANDSCAPE

There are cities that shelter you.

And there are cities that expose you.

New York in Taxi Driver is not a place you visit. It is a place you survive. It does not merely exist around Travis Bickle; it seeps into him, stains him, reshapes his inner weather. This city is not background, not setting, not geography. It is condition. It is disease. It is confession.

Martin Scorsese’s New York is a nocturnal organism — pulsing, sweating, restless. Streets glow with neon like infected wounds. Steam rises from manholes like the city exhaling rot. Rain falls incessantly, not romantically, but desperately, as if the world itself is attempting a baptism it knows will fail.

The brilliance of Taxi Driver begins here: with the recognition that alienation is not born inside Travis — it is incubated by the city. The film understands something essential about modern urban life: that loneliness is not the absence of people, but the absence of meaning amid crowds.

The City as a Moral Fever

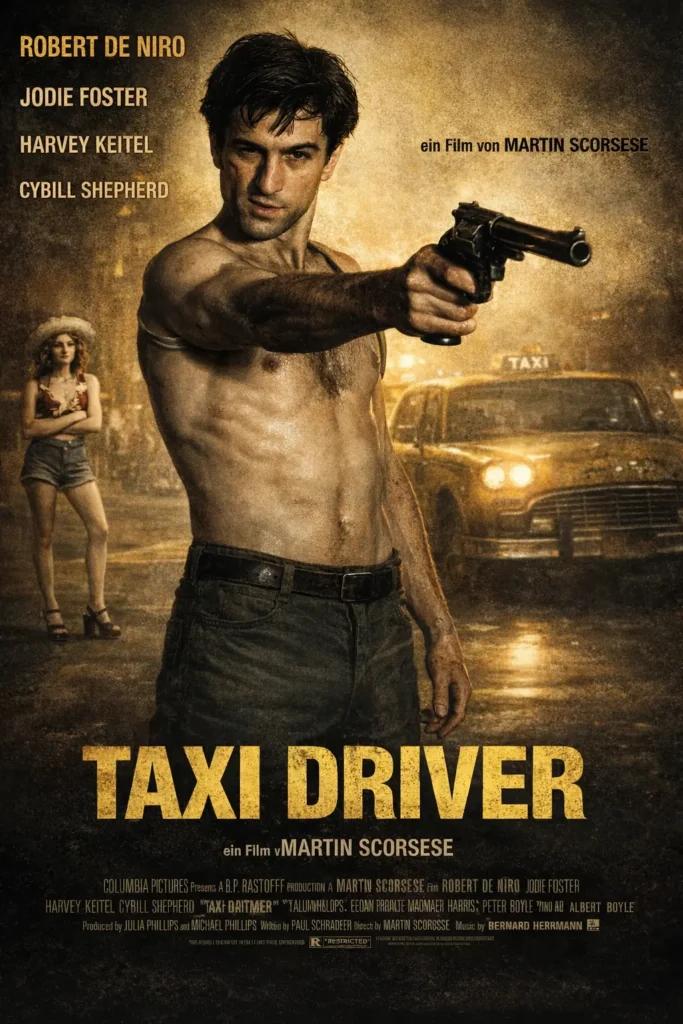

The opening shots of Taxi Driver announce its intent with surgical precision. A taxi emerges from smoke, headlights cutting through darkness like an animal pushing through fog. Bernard Herrmann’s score slides in — jazz that feels both seductive and sick. This is not the city waking up. This is the city already diseased.

Scorsese frames New York as a place where everything is visible and nothing is understood. Porn theaters glow openly. Hustlers roam freely. Political slogans hang in the air like decorations stripped of conviction. The city is loud, crowded, endlessly alive — and spiritually hollow.

This is not accidental ugliness. It is a realism sharpened into accusation.

Unlike classical Hollywood cinema, which often mythologized the city as a place of opportunity or danger-with-purpose, Taxi Driver shows urban life as entropy. Motion without progress. Sensation without connection. Desire without fulfillment.

Travis drives endlessly, night after night, through the same streets. The repetition is suffocating. He sees everything, yet participates in nothing. He becomes a witness to decay — and witnesses, when left alone too long, begin to believe they are judges.

Alienation as Atmosphere

Alienation in Taxi Driver is not delivered through exposition. It is atmospheric.

Travis works nights. He sleeps days. His circadian rhythm is inverted, placing him permanently out of sync with society. While others sleep, he watches. While others live, he drifts. Time itself becomes untrustworthy.

This temporal dislocation is crucial. Alienation is not just emotional separation — it is temporal exile. Travis exists in the city’s margins, moving through hours when the social contract loosens and the masks slip.

Scorsese reinforces this through pacing. Long takes stretch time. Traffic lights linger. The camera drifts instead of cuts. We are not rushed; we are trapped.

The city does not threaten Travis overtly. It ignores him. And that indifference is more corrosive than hostility.

The Taxi as Limbo

The taxi itself becomes a metaphysical space — a moving confessional, a glass cage, a purgatory on wheels.

Travis sits separated from the world by glass. He sees people but does not touch them. He hears voices but does not engage. The taxi allows proximity without intimacy — a perfect metaphor for modern alienation.

Each passenger represents a fragment of the city’s psyche: paranoia, lust, despair, boredom. Travis absorbs them silently, storing impressions without processing them. The result is psychological sediment.

Paul Schrader’s genius lies in understanding that alienation is cumulative. Travis does not snap suddenly. He collects impressions until they coagulate into ideology.

Loneliness Without Language

What makes Travis tragic — and dangerous — is not merely that he is lonely, but that he lacks the emotional vocabulary to understand his loneliness.

He does not say, I am sad.

He says, The city is filthy.

This displacement is central to the film’s realism. Many people do not experience alienation as pain; they experience it as judgment. The world feels wrong, not the self.

Travis’s voiceover diary is filled with moral observations masquerading as insight. He describes the city with disgust, but never interrogates his own inability to belong.

Alienation, left unexamined, curdles into superiority.

Insomnia as Metaphysics

Travis’s insomnia is not a symptom; it is a worldview.

Sleep is surrender. Connection. Vulnerability.

Travis cannot sleep because sleep requires trust — in the body, in the world, in tomorrow. Insomnia keeps him alert, armored, hyper-vigilant. It is the condition of a man who believes the world is hostile and must be monitored.

Scorsese films nights not as respite but as exposure. Darkness does not hide; it reveals. In the night city, everything is laid bare — including Travis’s isolation.

Urban Realism Without Romance

What separates Taxi Driver from stylized neo-noir fantasies is its refusal to aestheticize alienation.

Yes, the film is beautiful — but its beauty is sickly. Neon bleeds. Colors clash. The city glows like an infection under a microscope.

Michael Chapman’s cinematography avoids glamour. Long lenses compress space, making the city feel claustrophobic. Reflections fragment faces. Rain distorts vision.

Reality itself feels unreliable.

This is realism not as documentation, but as psychological truth.

The Crowd as Void

Perhaps the film’s cruelest insight is this: crowds do not cure loneliness. They intensify it.

Travis is surrounded by people constantly — passengers, pedestrians, coworkers — yet he is fundamentally untouched. The crowd becomes a reminder of exclusion.

This is the modern paradox Taxi Driver exposes with brutal clarity: the more populated the world becomes, the easier it is to disappear.

Alienation as Prelude

Though the film does not announce such divisions — we understand something essential.

The city did not make Travis violent.

It made him empty.

And emptiness, when paired with certainty, is one of the most dangerous states a human being can inhabit.

THE MIND OF TRAVIS — DIARY, PHILOSOPHY, AND INTERNAL WAR

Loneliness does not speak in silence.

It speaks in monologue.

If Act I of Taxi Driver is about the city that surrounds Travis Bickle, Act II is about the city that forms inside him. This is where the film tightens its grip, where atmosphere condenses into ideology, where observation hardens into belief.

Travis does not simply move through New York; he interprets it. And interpretation, when unchallenged, becomes doctrine.

At the heart of Taxi Driver lies one of the most radical narrative decisions in American cinema: the decision to let us live inside the thoughts of a man who is wrong.

The Diary as a Trap

Paul Schrader structures Taxi Driver around a diary — a device borrowed from his own struggles with isolation, despair, and moral absolutism. The diary voiceover is intimate, literary, hypnotic. It invites us in with vulnerability.

“Thank God for the rain,” Travis writes. “Which has helped wash away the garbage and the trash off the sidewalks.”

The line is poetic. It is also chilling.

Diaries feel truthful because they are private. But privacy does not guarantee insight. The diary in Taxi Driver becomes a closed system — a feedback loop in which Travis’s thoughts are never tested against reality. No one answers back. No one contradicts him.

This is the danger of interior monologue: it can masquerade as self-awareness while functioning as self-radicalization.

Unreliable Narration as Moral Strategy

Travis’s voiceover does not lie outright. It distorts.

He describes loneliness accurately, but misattributes its cause. He senses decay, but mistakes complexity for corruption. He feels powerless, but reframes that powerlessness as moral superiority.

Scorsese and Schrader never signal unreliability with gimmicks. There are no obvious contradictions, no sudden reveals. Instead, unreliability emerges gradually — through excess certainty.

Travis speaks with the calm assurance of a man who believes he sees clearly.

That belief is the warning.

Philosophy Without Humility

Taxi Driver is steeped in philosophy, but it is philosophy stripped of doubt.

Schrader, influenced deeply by Calvinism, existentialism, and transcendental cinema, creates in Travis a man obsessed with purity. The world is divided into clean and dirty, righteous and damned. There is no gray, because gray requires patience.

Travis does not ask questions. He renders verdicts.

This is not existential freedom — it is existential terror. Sartre argued that freedom demands responsibility. Travis wants responsibility without uncertainty, action without reflection.

He does not wonder whether he is right.

He assumes it.

The Mirror as Courtroom

Mirrors recur obsessively throughout Taxi Driver. Travis stares at himself, practices expressions, rehearses confrontations. The famous “You talkin’ to me?” scene is often misread as swagger or madness.

In truth, it is preparation.

Travis is both defendant and prosecutor, witness and judge. The mirror becomes a courtroom where the verdict is always guilty — but never his guilt.

He is not asking who he is.

He is deciding who deserves punishment.

Desire Without Intimacy: Betsy

Betsy represents Travis’s fantasy of redemption — not as a person, but as an idea.

She is light-colored, distant, elevated above the city’s filth. Travis does not know her; he projects onto her. She becomes proof that purity exists — and therefore must be defended.

The disastrous date sequence exposes Travis’s emotional illiteracy. Taking Betsy to a porn theater is not provocation; it is misunderstanding. Travis does not grasp social codes because he does not understand otherness.

When Betsy rejects him, Travis does not mourn the loss of connection.

He feels betrayed by the world for not conforming to his fantasy.

Rejection as Confirmation

Rejection does not soften Travis. It confirms him.

This is one of the film’s most devastating insights: for certain psychological structures, rejection is not corrective — it is catalytic.

Betsy’s rejection does not inspire introspection. It reinforces Travis’s belief that the world is corrupt and ungrateful. He does not ask what he did wrong.

He asks why goodness is punished.

Victimhood becomes ideology.

Masculinity After Vietnam

Travis is a veteran, but Taxi Driver refuses to dramatize war trauma explicitly. Vietnam exists as absence — as something that has already happened and left behind confusion.

Travis has been trained for vigilance, aggression, and survival. What he has not been trained for is ambiguity.

In civilian life, there is no enemy to identify, no objective to complete. Masculinity loses its script.

Travis fills that void with ritual: exercise, guns, routines. Discipline replaces meaning. Control replaces understanding.

This is masculinity untethered from community — strength without direction.

The Gun as Philosophy Made Metal

When Travis acquires guns, the film does not treat the moment as escalation. It treats it as articulation.

The gun is not merely a weapon. It is an answer.

It resolves ambiguity. It promises clarity. It transforms moral confusion into physical action.

The hidden sleeve gun is especially revealing — a mechanical extension of Travis’s desire for efficiency, secrecy, inevitability. Violence, once mechanized, feels righteous.

Iris and the Savior Complex

Travis’s fixation on Iris is framed as rescue, but rooted in possession.

He sees her youth as corruption’s final insult — innocence violated by filth. Saving Iris allows Travis to imagine himself as righteous without confronting his own failures.

The savior complex is seductive because it requires no reciprocity. Iris does not need to consent. She needs to be fixed.

Travis does not listen to Iris.

He decides for her.

Internal Conflict Without Resolution

What makes Travis terrifying is not that he lacks conflict — it is that his conflict resolves itself too easily.

Doubt flickers occasionally, but certainty extinguishes it quickly. His diary does not wrestle; it affirms.

By the time Travis shaves his mohawk — a ritualistic transformation — his internal war has ended.

He has chosen a side.

The Illusion of Transcendence

Schrader has described Taxi Driver as a story of a man seeking transcendence through violence.

This is the film’s darkest irony.

Transcendence traditionally implies moving beyond the self. Travis moves deeper into it. Violence does not free him from ego; it canonizes it.

He does not dissolve.

He crystallizes.

A Mind Sealed Shut

Travis’s mind is no longer porous. Nothing enters. Nothing leaves.

Loneliness has transformed into doctrine.

Alienation has become destiny.

The tragedy is complete — even before the blood.

VIOLENCE, POLITICS & MISREADING — BLOOD IN THE NATIONAL MIRROR

Violence does not ask to be understood.

It asks to be explained.

If Act II sealed Travis Bickle’s inner world, Act III detonates it against the outer one. This is where Taxi Driver ceases to be merely psychological and becomes unmistakably political — not in slogans or speeches, but in consequences. Blood spills, and suddenly meaning rushes in to fill the vacuum.

This act is about misreading: how violence is framed, how it is consumed, and how a society desperate for narrative coherence turns chaos into myth.

America After the Wound

Taxi Driver emerges from the wreckage of 1970s America — a nation psychologically destabilized by Vietnam, Watergate, urban decay, and the collapse of institutional trust.

Vietnam did not just end a war. It ended an illusion.

For the first time, American violence was broadcast into living rooms without the comfort of victory. The myth of moral clarity fractured. Soldiers returned not as heroes, but as reminders of ambiguity.

Travis Bickle is a product of that fracture.

He is what happens when a culture trained men for war but failed to teach them peace.

Violence as Language

Travis does not articulate his politics. He performs them.

His violence is not reactive — it is expressive. It is his way of entering the public conversation.

This is crucial: Travis does not kill out of rage alone. He kills to mean something.

In a society where attention is currency, violence becomes grammar.

The Political Assassination That Isn’t

The aborted attempt on Senator Palantine is often overshadowed by the film’s climax, but it is politically essential.

Palantine is empty rhetoric incarnate — smiling, vague, adaptable. He represents institutional politics stripped of conviction. Travis’s interest in killing him is not ideological disagreement.

It is existential assertion.

To kill Palantine would be to puncture the illusion that the system has coherence. It would force the nation to look at its own emptiness.

That Travis fails is important. He is not allowed to confront power directly.

Instead, he turns sideways.

The Shift from Politics to Spectacle

When Travis redirects his violence toward Sport and the brothel, the film enters its most disturbing territory.

The targets are undeniably vile. The imagery is horrifying. And yet, the act is framed — by newspapers, by public response — as heroic.

This is the film’s central political thesis:

Violence is not judged by intention, but by narrative convenience.

The Final Shootout: Anti-Climax as Truth

The climactic massacre is filmed without grandeur. It is chaotic, ugly, exhausting.

Scorsese drains violence of choreography. There is no rhythm, no elegance, no pleasure. Bodies collapse awkwardly. Blood pools excessively, absurdly.

The camera does not celebrate.

It endures.

This is not catharsis. It is collapse.

Blood as Abstraction

The infamous overhead shot — the camera lifting away from the carnage — feels almost documentary. It refuses intimacy at the moment intimacy would be most seductive.

Violence becomes abstraction.

This distancing is ethical. Scorsese understands that to linger lovingly would be to participate in the lie.

The Media Alchemy

What follows is more disturbing than the violence itself.

Newspapers frame Travis as a hero. Letters of praise arrive. The story is simplified, purified, narrativized.

The nation does what it always does: it edits.

Travis is not celebrated because he is healed.

He is celebrated because his violence aligns with a story the culture wants to tell.

The Politics of Recognition

Travis wanted to be seen.

And now he is.

This is Taxi Driver’s most brutal insight: recognition does not discriminate between sanity and pathology. It rewards visibility.

Violence works.

Not morally — narratively.

Masculinity Rewarded

Travis’s transformation into a folk hero exposes the gendered logic beneath the response.

He acted.

He asserted.

He imposed order through force.

These qualities are legible — even admirable — within certain myths of masculinity.

The cost is irrelevant.

Iris Returns Home

Iris’s rescue is treated as closure, but it is profoundly uneasy.

We are told she returns to her family, cleansed, restored. Her voiceover letter reads like propaganda — hopeful, simplified, grateful.

The complexity of her experience is erased.

Once again, the story demands neatness.

Misreading as Survival Mechanism

Societies misread violence not because they are evil, but because they are afraid.

Ambiguity is intolerable. Chaos must be shaped into meaning.

Travis survives because his story is easier than the truth.

The Smile in the Mirror

In the film’s final moments, Travis catches his reflection in the rearview mirror. His eyes flicker.

Is he calm?

Or merely waiting?

The film refuses to answer.

This is not redemption.

It is a pause.

Violence Without End

Taxi Driver ends not with closure, but with a warning.

Nothing has been resolved.

The conditions remain.

The city still festers.

The rain still falls.

A Nation That Mistakes Blood for Meaning

Act III exposes the ultimate tragedy: Travis’s violence is not aberration.

It is absorption.

The nation does not reject him.

It understands him.

CINEMA ITSELF — HOW TAXI DRIVER REDEFINED THE LANGUAGE OF FILM

Some films tell stories.

Others invent grammar.

By the time Taxi Driver reaches its final moments, something irreversible has already occurred — not only within Travis Bickle, not only within the city or the nation, but within cinema itself. Act IV steps back from character and politics to confront the film as an object, a machine, a language experiment that permanently altered how movies could think.

This is where Taxi Driver reveals its final, enduring power: not merely in what it depicts, but in how it teaches cinema to see.

Direction as Moral Architecture

Martin Scorsese’s direction in Taxi Driver is often praised for its intensity, but its true achievement lies in restraint.

Scorsese never collapses fully into Travis’s subjectivity. He hovers — close enough to feel the heat of Travis’s thoughts, distant enough to retain judgment. This moral distance is the film’s spine.

Every directorial choice asks an ethical question:

How close can cinema get to pathology without endorsing it?

Scorsese answers not with dialogue, but with framing, pacing, and omission. We are implicated, but never absolved.

The Refusal of Traditional Catharsis

Classic Hollywood cinema resolves conflict through restoration: the hero grows, the world stabilizes, order returns.

Taxi Driver rejects this grammar entirely.

The film ends where it began — with Travis driving, watching, narrating. The apparent calm is cosmetic. Nothing essential has changed.

This refusal was radical.

Scorsese offers no moral release, no lesson neatly learned. Instead, he leaves the audience suspended — forced to wrestle with discomfort long after the credits roll.

Screenplay as Psychological Loop

Paul Schrader’s screenplay is deceptively simple in structure, yet philosophically dense.

The diary voiceover creates circularity. Thoughts repeat. Observations harden. Language becomes ritual.

There is no classical character arc because Travis does not evolve.

He fixates.

This was revolutionary. Cinema had rarely allowed a protagonist to remain fundamentally unchanged — and still demand engagement.

Schrader replaces development with deepening.

Cinematography as Subjective Reality

Michael Chapman’s cinematography does not merely record events; it simulates perception.

Long lenses compress space, trapping Travis in crowds even when he is alone. Slow tracking shots mimic the drift of insomnia. Reflections fragment faces, turning identity into collage.

Color operates psychologically. Sickly greens and reds bleed into the frame, suggesting contamination. Neon becomes nervous system.

Reality bends.

This visual subjectivity would become foundational for modern cinema.

Camera Movement as Consciousness

The camera in Taxi Driver often moves independently of Travis — gliding, lingering, observing.

This creates a haunting effect: the sense that something is watching him watching the world.

Cinema itself becomes a consciousness.

This strategy prefigures the work of filmmakers like David Fincher, Paul Thomas Anderson, and Darren Aronofsky — directors who treat the camera as psychological participant.

Editing and Temporal Dread

The film’s editing resists momentum. Scenes stretch. Time dilates.

This slowness is not indulgent; it is diagnostic.

We feel Travis’s insomnia. His waiting. His obsession.

Cinema becomes experiential rather than narrative.

Bernard Herrmann’s Final Gift

Bernard Herrmann’s score for Taxi Driver is one of the great ironies in film history — lush, romantic music for a story of decay.

The jazz saxophone theme suggests longing, nostalgia, vulnerability. It humanizes Travis even as his actions estrange us.

Then the music fractures.

Harmony dissolves into shrieks and dissonance, mirroring Travis’s psychic collapse.

Herrmann’s death shortly after completing the score gives it the quality of a requiem — not just for Travis, but for an era of American innocence.

Sound Design as Isolation

Beyond music, Taxi Driver uses sound sparingly and strategically.

Street noise hums like static. Silence stretches uncomfortably. Dialogue often feels slightly detached, as if filtered through exhaustion.

The world sounds distant — unreachable.

Performance as Exposure

Robert De Niro’s performance is not expressive in the traditional sense. It is exposed.

He withholds charm. He minimizes affect. His stillness becomes threatening.

De Niro does not ask us to like Travis.

He asks us to recognize him.

This approach would redefine screen acting — paving the way for performances that privilege interiority over likability.

The Birth of the Modern Anti-Hero

Taxi Driver helped crystallize the modern anti-hero: isolated, morally ambiguous, psychologically fractured.

Travis Bickle is not a rebel or a rogue.

He is a symptom.

This shift opened cinema to darker, more honest character studies — films that refused reassurance.

Influence Without Dilution

Countless films have borrowed Taxi Driver’s imagery — the mirror, the city at night, the lonely man drifting.

Few have understood its discipline.

What makes Taxi Driver endure is not style, but restraint — its refusal to explain itself away.

Why It Still Matters

The world that produced Travis Bickle did not vanish.

Alienation intensified.

Media cycles accelerated.

Violence became spectacle.

The film remains current because its diagnosis remains accurate.

Cinema as Warning System

Taxi Driver functions as an early warning — a film that sensed cultural fractures before they became visible.

It asks what happens when loneliness meets certainty.

It does not answer.

It observes.

The Final Look

The last shot of Taxi Driver — Travis’s eyes in the mirror — is cinema at its most unsettling.

A flicker.

A possibility.

A future unresolved.

Scorsese cuts before certainty can form.

That cut is mercy.

Why Taxi Driver Is a Masterpiece

Because it refuses comfort.

Because it understands violence without romanticizing it.

Because it trusts the audience enough to disturb them.

Because it transformed cinema from a mirror of action into a mirror of mind.

Taxi Driver is not a film you finish.

It is a film that finishes you.

A FILM THAT DOES NOT SLEEP

There are films that belong to their era.

And then there are films that diagnose eras yet to come.

Taxi Driver does not age because it is not about fashion, politics, or technology.

It is about what happens when human beings lose the ability to connect — and mistake isolation for truth.

The city changes.

The sickness adapts.

The night remains.

And somewhere, a man is still driving.

AFTERLIFE — TAXI DRIVER IN THE MODERN SOUL

Some films end.

Others linger.

A few keep watching.

If the earlier acts of Taxi Driver trace a descent — into city, mind, nation, and cinema — Act V exists in the afterlife. This is where the film stops being an artifact of 1976 and becomes a recurring symptom of the present. A film’s masterpiece status is not decided by awards or influence alone, but by recurrence: how often it returns, how stubbornly it refuses to stay buried.

Taxi Driver survives because it is not sealed in its era. It migrates.

From Urban Decay to Digital Isolation

The city Travis drives through no longer exists in the same physical form. Times Square has been sanitized. Neon replaced by LED. Porn theaters by algorithms.

But alienation has not disappeared.

It has simply gone indoors.

Loneliness is no longer confined to streets at night. It lives on screens, in feeds, in endless scrolls that simulate connection while withholding intimacy. Travis needed a taxi to observe the world without touching it.

Today, we need only a phone.

The Diary Becomes the Internet

Travis’s diary was private. Dangerous, yes — but contained.

The modern diary is public.

Blogs, forums, comment sections, manifesto-videos — interior monologue is now broadcast. Thoughts once whispered to notebooks are amplified, echoed, reinforced.

The closed system Schrader warned about has become networked.

Certainty spreads faster than doubt.

Radicalization as Narrative Arc

Taxi Driver predicted something chillingly specific: that alienation, when paired with narrative hunger, seeks escalation.

Travis did not want destruction for its own sake.

He wanted meaning.

Modern radicalization follows the same arc: isolation → grievance → identity → action. Violence becomes punctuation in a story that finally feels coherent.

The film does not excuse this.

It explains it.

Why Audiences Still Misread Travis

Every generation tries to claim Travis Bickle.

Some see rebellion.

Some see masculinity restored.

Some see victimhood justified.

This misreading is not accidental — it is the film’s trap, set deliberately.

Taxi Driver exposes the viewer’s own moral reflexes. How quickly do we sympathize? At what point do we withdraw? Where do we draw the line — and why there?

The film is a test.

Many fail it.

Masculinity in Perpetual Crisis

Travis represents a masculinity untethered from community and purpose.

That crisis did not resolve.

It mutated.

Economic precarity, cultural displacement, and social atomization have left many men narrating their lives in isolation, searching for scripts that promise dignity without vulnerability.

Taxi Driver remains relevant because it understands that masculinity without belonging seeks domination.

The Aestheticization of Pain

One of the film’s most uncomfortable legacies is how often its imagery is borrowed without its ethics.

The lone man.

The mirror.

The gun.

Detached from context, these become symbols of empowerment rather than warning.

Scorsese knew this risk.

He took it anyway.

That courage is part of the film’s greatness.

Cinema After Taxi Driver

Modern cinema’s obsession with damaged men — from vigilantes to anti-heroes — traces back here.

But Taxi Driver differs from its descendants in one crucial way: it never flatters its protagonist.

It offers intimacy without approval.

This distinction has been eroded over time.

The afterlife of Taxi Driver is filled with echoes that misunderstood the original sound.

Why the Film Still Feels Dangerous

Most classic films feel safe.

Taxi Driver does not.

It still unsettles, not because of violence, but because of recognition. Because parts of Travis feel familiar — not admirable, but legible.

The film whispers an accusation:

This is not alien. This is adjacent.

Art as Early Warning

Great art senses pressure before rupture.

Taxi Driver sensed loneliness curdling into ideology decades before the vocabulary existed.

It is not prophetic because it predicts events.

It is prophetic because it identifies patterns.

Watching Ourselves Watching

To watch Taxi Driver today is to become aware of your own gaze.

Do you lean forward?

Do you recoil?

Do you rationalize?

The film does not move.

You do.

The Ethics of Representation

Scorsese never tells us what to think.

He shows us what thinking without interruption looks like.

This is the film’s ethical gamble: that exposure can function as critique.

It trusts the audience.

That trust is rare now.

Why the Film Refuses Closure

Closure would be dishonest.

The problems Taxi Driver examines have no ending — only management.

The final mirror glance still trembles because the future remains open.

That openness is the horror.

The Loneliness That Endures

Technology did not cure loneliness.

It refined it.

The city expanded inward.

The taxi became virtual.

The night never ended.

The Film as Companion

For some, Taxi Driver becomes a mirror.

For others, a warning.

For a few, a companion during difficult nights.

The film does not judge this.

It observes.

Final Testament

Taxi Driver is a masterpiece not because it is perfect, but because it is honest about imperfection.

It does not promise healing.

It documents fracture.

And by doing so, it remains alive.

As long as people feel unseen.

As long as cities hum without listening.

As long as loneliness searches for meaning.

This film will keep driving.

Why Quentin Tarrantino feels different…

Ever wondered why we love evil characters in fiction….