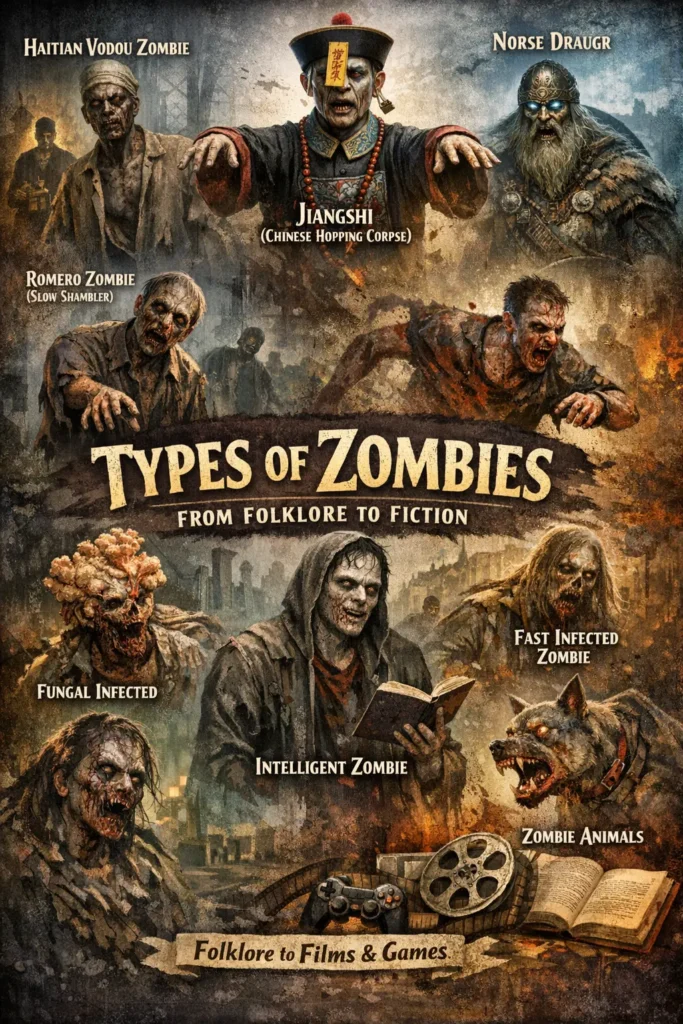

Introduction: The term “zombie” originally comes from Haitian folklore, where a zombi (Haitian French) or zonbi (Haitian Creole) is a corpse reanimated by magical means (typically Vodou rites) and controlled as a mindless slave. In modern usage, however, “zombie” usually denotes an undead creature in horror fiction – often a reanimated human corpse (or infected living person) driven by a ravenous hunger for flesh. This concept has evolved dramatically: early Haitian zombies emphasized enchantment and servitude, whereas contemporary zombies are typically portrayed as contagious and cannibalistic (a change popularized by George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead and its successors). The proliferation of zombies across film, games, and literature has led to many distinct “types” of undead with varying origins, abilities, and intelligence. This report surveys the major zombie archetypes in folklore and media, their origins and first appearances, and compares their traits (speed, intellect, threat level, etc.) in tables and narrative.

1. Folkloric and Mythological Zombies

Traditional folklore around the world features undead beings that resemble or inspired today’s zombies. These are often animated by magic or curses rather than science. Below are some of the most famous folkloric types:

- Haitian Vodou Zombies (“Zombi”): In Haitian and West African tradition, a zombi is a dead person resurrected by a sorcerer (a bokor in Vodou) to serve as a slave. The revived corpse (or even sometimes a still-living but drugged person) has no free will of its own and obeys the bokor’s commands. Haitian texts and colonial records (17th–18th centuries) describe zombies as symbols of slavery’s horror: West African slaves in Haiti were sometimes said to be buried alive and later used as magically compelled laborers. Ethnobotanists (e.g. Wade Davis) have reported that Haitian bokors use a “zombie powder” containing tetrodotoxin (from pufferfish poison) and other substances to induce a deathlike paralysis. One famous case (Clairvius Narcisse, 1962) involved a man declared dead and buried who resurfaced 18 years later claiming he had been made into a zombie slave. In popular culture, Haitian zombies were first introduced to the West in W. B. Seabrook’s 1929 book The Magic Island and Hollywood’s White Zombie (1932). Characteristics: Haitian zombies are usually slow and passive, lacking self-awareness, and serve a master rather than attacking others. Because they were intended as laborers, they typically are not depicted as flesh-eaters. They can often be “cured” (revived to normal life) by breaking the magic or deathlike spell.

- Chinese “Jiangshi” (Hopping Corpses): In Chinese legend, a jiangshi (殭屍, “stiff corpse”) is an undead created when a corpse is reanimated by sorcery or improper death rituals. Jiangshi are traditionally depicted wearing Qing-dynasty funeral garments and Taoist talismans; they move by hopping with outstretched arms. Folklore says they kill the living by draining their qi (life energy) rather than drinking blood. Unlike Western zombies, a very old jiangshi can move faster or even fly, but they are nonetheless mindless and follow simple instincts. Jiangshi first appeared in Qing-era tales (18th–19th century), but became widely known through Hong Kong cinema. The 1985 film Mr. Vampire (香港殭屍) sparked a boom in “hopping zombie” movies. (Figure: Cosplayers in jiangshi costumes at a Taiwanese festival, embodying the classic hopping Chinese zombie.)

- Norse “Draugr” (Undead Guardians): In medieval Norse sagas, a draugr (plural draugar) is the undead body of a deceased Viking or sorcerer that rises from its burial mound to haunt the living. Draugar were said to guard treasure, curse kin, and kill intruders. They often retain intelligence and magical powers, unlike mindless zombies; for example, sagas describe draugar shapeshifting, controlling weather, and wrestling with heroes. Physically, draugar have superhuman strength, a decaying “death-blue” or black complexion, and exude a foul stench. Because they were revenged dead rather than plague victims, draugar are effectively conscious undead that remember past grievances. (E.g. Grettir’s saga features a draugr that learned to use fire and stratagem.) Modern fantasy sometimes calls these “Norse zombies” for convenience.

- Other Traditional Undead: Various cultures have analogous undead legends. For example, European revenants in the Middle Ages – bodies thought to return from the grave – share zombie-like traits (the earliest “canon” usage of zombie in English stems from colonial accounts of Haitian revenants). Archaeology shows even ancient Greeks staked or pinned skeletons to prevent reanimation. The Egyptian mummy of lore (a resurrected corpse guarding tombs) and the Japanese jikininki (corpse-eating ghosts) are undead spirits with some zombie-like qualities, though classically they act more like guardians or spirits than rabid attackers. In many tales (Biblical Ezekiel’s dry bones, Celtic banshees, etc.), the boundary between ghost and zombie blurs.

Summary of Folkloric Zombies: Haitian vodou zombi and Chinese jiangshi exemplify classic “magical” zombies – reanimated by curse or sorcery. Norse draugar mix the zombie motif with personal vengeance and sorcery. These undead typically lack the viral contagion motif of modern stories. Behaviors: they are generally slow or limited in movement (a bound zombie or hoppping corpse), low in intelligence, and motivated by their master’s will or grudges. As Britannica notes, actual Haitian “zombis” in history were likely living people drugged by bokors (e.g. with scopolamine from toads and pufferfish) rather than true reanimated corpses.

2. The Zombie Archetype in Modern Media

In the 20th–21st centuries, zombies leapt from folklore into global pop culture. The portrayal of zombies has evolved rapidly, spawning many subtypes. Below we trace this evolution:

- Early Western Zombie Fiction (1900s–1950s): The Western “zombie” appears sporadically in literature and film before Romero. Early writers like Ambrose Bierce (1891) and H. Rider Haggard (1922) hinted at reanimation, but W.B. Seabrook’s The Magic Island (1929) popularized the Haitian zombie in the US. The first major zombie film was White Zombie (1932), a horror movie in which Bela Lugosi plays a voodoo master reanimating slaves. Other mid-century films (“I Walked with a Zombie” 1943) leaned on Caribbean tropes. Richard Matheson’s 1954 novel I Am Legend treated zombies as victims of a contagion (though actually vampire-like, it influenced Romero).

- George Romero and the Modern Zombie (1968–1980s): George Romero’s Night of the Living Dead (1968) redefined zombies in popular imagination. Here, the zombie is an undead cannibal, attacking survivors and craving human flesh. Importantly, Romero’s zombies arise from unknown causes (possibly radiation from a satellite) rather than magic. They are slow-moving, relentless shamblers that must be killed by destroying the brain. Romero’s success spawned sequels Dawn of the Dead (1978) and Day of the Dead (1985), and inspired other franchises (Zombi 2 in Italy, Return of the Living Dead in the US). Notably, Return of the Living Dead (1985) popularized the trope that zombies specifically crave brains. During this era, zombies became firmly associated with plague-like outbreaks and societal collapse themes. Romero’s writers even noted that any dead human (regardless of cause of death) would reanimate, implying a new ubiquitous infection paradigm.

- Zombie Renaissance (1990s–2000s): After a lull in the 1980s, zombies surged again in the late 1990s and 2000s. Key catalysts were video games: the 1996 games Resident Evil and The House of the Dead featured hordes of mutated zombies. These games (and others like Left 4 Dead and Dead Rising) introduced more violent action-oriented zombies. As a result, 2000s films began showing faster, more aggressive undead. For example, 28 Days Later (2002) dispensed with slow shuffling and instead presented humans infected by a “rage virus” who sprint and attack with feral speed. The Resident Evil film series (2002–2016) likewise popularized violent, resilient “T-virus” zombies and related mutants. Romero himself returned with Land of the Dead (2005), where zombies even begin to learn from experience (e.g. using weapons). Meanwhile, zombie comedy (Shaun of the Dead 2004, Zombieland 2009) and international hits (Train to Busan 2016) kept the genre fresh.

- 21st-Century Variants: In the 2010s, new twists emerged. Television like The Walking Dead (2010–present) portrayed apocalyptic survival against hordes of “walkers” that behave much like Romero’s slow zombies. Other films (World War Z 2013) and shows (Black Summer) leaned into super-fast swarm zombies that run in packs. A parallel trend humanized zombies: movies like Warm Bodies (2013) and series like iZombie (2015) depict sentient or “romantic” zombies who feel emotion or even fall in love. Video games have also diversified the undead: The Last of Us (2013) introduced fungal-infected zombies with stages (runners, clickers, bloaters) based on a mutated Cordyceps fungus.

Summary of Evolution: In sum, zombie archetypes have shifted from magical undead (folk belief) to scientifically-inspired contagions. The “classic” zombie (slow, undead corpse, brain needed to kill) traces back to Romero, while variations like fast zombies, infected survivors, and partially sentient undead arose later. The zombie motif has proved adaptable, serving as metaphor for disease, consumerism, and other modern anxieties.

3. Types of Zombies by Origin and Behavior

Zombies in fiction can be classified by how they arise and how they behave. The table below compares major zombie variants by origin (magical vs. biological), typical attributes, and examples:

| Zombie Type | Origin/Cause | Movement | Intelligence | Behavior/Traits | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haitian Vodou Zombie | Sorcery/Vodou (necromancy) | Slow (stumbling) | None (mindless, slave) | Corpses revived as personal servants, no self-will. Not flesh-eaters. | Haitian folklore, White Zombie (1932) |

| Romero-Style Zombie | Unknown (possibly radiation) | Very slow (shambling) | Minimal (instinct) | Classic undead; attacks any living human on sight; killed by brain destruction. Often decaying flesh. | Night of the Living Dead (1968), The Walking Dead |

| Fast Infected Zombie | Biological virus or pathogen | Fast (running, agile) | Low (animalistic) | Highly aggressive “rage”-infected; can sprint, jump; spread infection via bites. | 28 Days Later (2002), World War Z (2013), Train to Busan (2016) |

| Resident Evil Zombie | T-Virus (genetic bio-weapon) | Medium (shuffler, can run) | Low (basic instincts) | Reanimated by virus; often seen in hordes; some mutate into faster “Crimson Heads” on respawn. | Resident Evil game/film series (1996–2016) |

| Fungal Infected | Cordyceps-style fungus | Crawling to moderate | None (driven by fungus) | Humans infected by fungus; slowly turn into monsters (runners → blind “clickers” → hulking bloaters). Depicted like monsters. | The Last of Us (2013 game/2023 show), The Girl with All the Gifts (2014) |

| Chinese Jiangshi | Dark magic/curse (sorcery) | Moderate (hopping) | None (instinctual) | Reanimated corpse; wears Qing-era clothes; kills by qi-draining. Often neutralized by sticky talismans on forehead or by hitting limbs. | Mr. Vampire (1985) films, Chinese folklore |

| Norse Draugr | Sorcery/curse (revenant) | Slow (guards barrows) | High (cunning) | Powerful undead; guards treasure; uses sorcery (e.g. shape-shifting); must be subdued by heroes. Impervious to normal weapons. | Norse sagas (e.g. Grettir’s Saga), Skyrim (game) |

| Intelligent/Sentient | Various (often virus+mutation) | Varies | High | Zombies that retain personality or speech, often plot or form societies. They may seek treatment or companionship instead of feeding. | Warm Bodies (2013, romantic zombie), iZombie (TV), Bone Song (novel) |

| Other/Variant Zombies | Varies (e.g. radiation, demons) | Varies | Varies | Includes zombie animals (e.g. zombie dogs), insect/parasite controllers, or supernatural zombies (e.g. mummies, zombies turned by technology). | Resident Evil zombie dogs, Skylar(2022, plant zombies), Re-Animator(1985, chemical) |

Each type differs in threat level and behavior: Haitian zombies are low-threat to the living (they obey masters), whereas viral or fungal zombies are typically highly dangerous predators. Fast zombies (28 Days, World War Z) are far more lethal in combat, while classic Romero zombies require headshots but can overwhelm by numbers. Intelligence ranges from none (standard zombies) up to full human in “romantic” zombies – a spectrum reflecting the story’s needs.

4. Evolution of the Zombie Archetype Over Time

The zombie myth has transformed significantly over centuries. Key evolutionary stages include:

- 17th–19th centuries: Folkloric concept (African and Haitian roots, “evil dead” stories). Fear of dead rising appears in ancient graves.

- Early 20th century: Introduction of Haitian zombies to Western audience (Seabrook’s Magic Island, 1929) and first horror films (White Zombie, 1932). Zombies still meant enchanted slaves.

- Post-Romero (1970s–1990s): Emergence of the “walking corpse” definition. Romero’s 1968 film gave zombies a new identity as flesh-eating ghouls. The 1970s–80s saw zombies as metaphors (consumerism in Dawn of the Dead 1978) and brain-eating humor (Return…Dead 1985). Zombie fiction in novels and comics became popular (e.g. Pride and Prejudice and Zombies in 2009).

- Early 2000s: “Infection” becomes main cause. Films like 28 Days Later (2002) reframe zombies as a fast-spreading disease. High-speed zombies inspired by video games appeared (House of the Dead, Resident Evil in movies). The “zombie apocalypse” genre (complete societal collapse) takes off (Walking Dead, World War Z).

- 2010s–Present: Diverse subgenres flourish. We see romantic/humanized zombies, international variations (Korean Train to Busan, Japanese One Cut of the Dead), and a return to slow zombies in some horror (e.g. It Stains the Sands Red 2016). The zombie remains a pop-culture staple, reflecting each era’s fears (slavery, nuclear war, pandemic, social isolation, etc.).

Throughout this timeline, certain constants remain: the need to destroy the brain (in most portrayals) and the symbolism of unchecked consumption. But the form of the zombie shifts. Early zombies were mindless servants; later zombies became mindless threats; now they sometimes reclaim humanity.

5. Zombie Traits: Behavior, Speed, and Intelligence

Speed: Traditional zombies (Romero-style) are slow walkers, often depicted as shambling or dragging limbs. This makes them less individually deadly but dangerous in hordes. Modern variations introduced fast zombies: for instance, 28 Days Later and World War Z feature running zombies that sprint and leap. These are explicitly contrasted with the old style; as Wikipedia notes, “Night of the Living Dead” zombies are slow, while some films depict fast-moving zombies. Video games accelerated this trend: Resident Evil and House of the Dead (1990s) introduced quick, agile undead. In general, speed can range from nearly immobile (crawlers) to superhuman.

Intelligence: Most zombies in horror are non-intelligent – they act on instinct. They do not strategize or speak, beyond rudimentary recognition (e.g. Walking Dead walkers react to sound and movement). However, exceptions exist. Romero’s later works suggested zombies can learn (e.g. learning to use weapons in Land of the Dead). Comedic or romantic zombies (like Warm Bodies) often retain memories, even speech, symbolizing the return of humanity. A few stories (e.g. I Am Legend) blur the line by portraying infected humans who act strategically. For table comparisons, “intelligence” is graded as none/minimal for typical undead vs. human-level for sentient variants.

Behavior and Threat Level: Behavior is dominated by hunger. Zombies relentlessly pursue living victims. Threat level depends on type: Voodoo zombies pose little danger unless ordered to harm; classical zombies (Romero/Walking Dead) threaten safety only in numbers; fast/infected zombies present an immediate lethal threat; special mutants (e.g. Tyrants in Resident Evil, or game “Tank” zombies) can kill even armed survivors easily. Tables below summarize these differences.

- Example Differences: Return of the Living Dead (1985) introduced zombies that specifically say “Braaaains!”, a comedic twist on flesh-eating. In Train to Busan, zombies arise from a chemical spill and run incredibly fast. The Girl with All the Gifts uses a fungal infection that causes children to appear normal except when hungry. These examples illustrate how zombie behavior (attack method, speed, intelligence) varies by origin story.

Key Trait Comparisons:

- Kill method: Traditional zombies require destroying the brain; some lore adds fire or sunlight as weaknesses.

- Senses: Almost all zombies hunt by sight, smell, or sound. Romero’s, for example, are attracted to noise.

- Social organization: Herd mentality is common (zombies often move in crowds). Some works feature zombies using rudimentary tactics (e.g. forming barricades in Day of the Dead).

- Intangible undead: Some stories have ghost-like zombies (the Night of the Living Dead ghouls were called such), but these are rare in modern zombie fiction.

6. Zombies Across Media

Zombies appear in nearly every entertainment medium. Notable examples include:

- Film/TV: From Night of the Living Dead to The Walking Dead, zombies dominate horror cinema/TV. Classics include Dawn of the Dead (1978), Shaun of the Dead (2004 comedy), 28 Days Later (2002), World War Z (2013), Train to Busan (2016), and many international titles. TV shows like Fear the Walking Dead and iZombie expand the zombie trope. Animated features (Corpse Bride) and even musicals/comedies occasionally use the undead motif.

- Literature: Zombie fiction is a distinct genre now. George Romero co-wrote “Night of the Living Dead” novelization; Max Brooks’s World War Z (2006) and Zombie Survival Guide (2003) were bestsellers. Stephen King has written on zombies (Cell). Mashups like Pride and Prejudice and Zombies (2009) brought zombies into other genres. Romance/YA novels (Warm Bodies, Generation Dead) have reinterpreted zombies.

- Video Games: Zombies are ubiquitous in gaming. The Resident Evil (1996– ) and Left 4 Dead (2008) series are famous for zombie enemies. RPGs (e.g. The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim) include zombie NPCs. Survival games (DayZ, Dying Light), action shooters (Dead Island, COD Zombies mode), and indie titles (Project Zomboid) all feature zombie themes. These games often introduce “special infected” types with unique abilities (see Table).

- Tabletop and RPGs: Zombie war-games and board games (e.g. Zombies!!!, Dead of Winter) allow group play against undead. Tabletop RPGs like Dungeons & Dragons and World of Darkness have zombie or zombie-like creatures (mummies, revenants) as monsters.

7. Behavior and Threat Comparison

Finally, we compare zombie types by concrete traits:

- Speed: Classic zombies: very slow (lumbering gait). Fast zombies: sprinters, athletic, often climbing obstacles (as in 28 Days Later, World War Z). Crawlers (zombies with disabled legs) are very slow. Some mutated boss zombies move surprisingly fast given size (e.g. “Brutes”).

- Intelligence: Standard zombies have no intelligence: they operate on primal hunger. Some retain a fragment of personality (Bub in Day of the Dead remembers how to use tools). Intelligent zombies (rare subgenre) can reason or communicate (Warm Bodies, iZombie).

- Infection Method: Folkloric zombies: magical control, not contagious. Romero/modern zombies: often virus/bacteria/gas infection (contagious by bite). Parasitic zombies: infection by fungus or parasite (not directly transmissible but spreads host-to-host).

- Threat Level: Haitian/voodoo zombies are low-threat (they don’t harm people). Single Romero zombies are low-threat (slow, easily avoided), but masses are dangerous. Fast/infected zombies are high-threat (lethal chase). Smart zombies (if present) are extremely dangerous. Even the weakest zombie type can kill via bite/infection if unchecked, as in I Am Legend.

8. Evolutionary Context

Over centuries, zombies reflect cultural fears. The earliest folklore (Africa, Haiti) tied zombies to slavery and the loss of free will. Mid-20th-century Western zombies tapped Cold War anxieties (radiation, conformity). Recent zombies echo pandemics and social breakdown. As scholars note, “other monsters threaten individuals, but the living dead threaten the entire human race” – once the infection starts, no one is safe.

In summary, zombies have many faces: from the necromantic Haitian zombi to the fast rabid infected of modern thrillers, to supernatural variants across cultures. Each type has a distinct origin story, behavior pattern, and cultural meaning. The tables above and discussion have cataloged these variations. As a genre, the zombie continues to evolve, bridging ancient myths and futuristic fears.

Know about Tim Burton’s portrayal of absurd and surreal characters…