Section I — The First Time I Realized Something Was Wrong

I remember the first time I caught myself admiring a character I was supposed to hate.

Not in a loud way. Not with claps or cheers. It was quieter than that — more dangerous.

I was sitting alone, watching a film late at night. The room was dark, the kind of darkness where the screen becomes the only source of truth. A character spoke calmly while everyone else panicked. He wasn’t shouting. He wasn’t pleading. He wasn’t explaining himself. He was simply… certain.

And I felt it — that unsettling pull.

Not agreement. Not approval.

Recognition.

That moment stayed with me longer than the film itself. Long after the credits rolled, the question lingered: Why did that feel powerful? Why did someone so morally broken feel so composed, so magnetic, so strangely alive?

That question — uncomfortable, almost embarrassing — is where this entire essay begins.

The Quiet Confession Most Viewers Never Say Out Loud

Most people won’t admit this openly, but many of us have felt it:

“I shouldn’t like this character… but I do.”

It’s the thought that sneaks in when Hannibal Lecter smiles politely, when Patrick Bateman delivers a monologue with chilling clarity, when the Joker laughs in the middle of societal collapse, or when Johan Liebert calmly dismantles a human being without raising his voice.

We reassure ourselves quickly:

- I like the performance, not the character.

- It’s just good writing.

- I’m interested psychologically, not emotionally.

And sometimes that’s true.

But sometimes — if we’re honest — it’s more than that.

Because fascination is not neutral. It’s emotional. It’s visceral. It’s the body leaning forward before the mind catches up.

This essay isn’t about shaming that reaction. It’s about understanding it.

Cinema as a Safe Place for Dangerous Curiosity

Cinema does something real life cannot: it allows us to approach danger without consequence.

We can sit inches away from murderers, manipulators, narcissists, and nihilists — and walk away untouched. No blood on our hands. No moral cost. Just questions.

And human beings are curious creatures.

We slow down near accidents. We read about crimes we claim to hate. We listen more carefully when someone speaks with absolute certainty — even when that certainty is terrifying.

These characters are not just villains.

They are permission slips.

Permission to:

- Look at power without responsibility

- Observe cruelty without consequence

- Feel control without guilt

- Explore identity without commitment

Cinema becomes the laboratory where we test forbidden emotions.

The Lie We Tell Ourselves About “Normal” People

There is a comforting myth we like to believe:

That good people are calm.

That bad people are loud.

That violence announces itself.

That evil looks chaotic.

Cinema breaks that myth.

Hannibal Lecter is polite.

John Doe is methodical.

Johan Liebert is gentle.

Patrick Bateman is professional.

Willy Wonka smiles.

They don’t look like monsters.

And that’s precisely what unsettles us.

Because if darkness doesn’t always scream… then how do we recognize it?

And more disturbingly — if composure, intelligence, confidence, and eloquence can exist alongside cruelty… what does that say about the traits we admire every day?

This is where admiration begins to feel dangerous — not because we want to imitate violence, but because we are forced to confront a truth:

Many traits we associate with strength are morally neutral.

They can belong to heroes.

They can belong to monsters.

The Alpha Illusion and the Hunger for Control

At some point, the conversation always turns to the word alpha.

Alpha male. Alpha presence. Alpha energy.

In cinema, this usually means:

- Someone who doesn’t seek validation

- Someone who commands attention without effort

- Someone who acts instead of reacts

- Someone who seems immune to fear

In real life, most of us rarely feel like that.

We hesitate.

We doubt.

We overthink.

We seek approval.

So when a character moves through the world with absolute self-belief — even if that belief is warped — it scratches a deep psychological itch.

Not because we want their morality.

But because we crave their certainty.

Audience Reviews: The Language of Unease

If you read audience reviews carefully — not the polished critic essays, but raw comments — a pattern emerges.

People don’t say:

“He’s right.”

They say:

“He’s terrifying but fascinating.”

“I hated myself for liking him.”

“I couldn’t stop watching.”

“Something about him stayed with me.”

That language matters.

It tells us this isn’t about ideology.

It’s about impact.

These characters leave residues in the mind. They linger. They echo.

And what lingers is usually something unresolved.

The Beginning of Self-Reflection

When I look back, I realize my fascination with these characters wasn’t about violence at all.

It was about:

- Emotional restraint

- Psychological clarity

- Freedom from social performance

- Power without apology

Things many of us suppress in order to survive politely.

Cinema gave those suppressed traits a face.

Sometimes a beautiful one.

Sometimes a terrifying one.

And the truth is — ignoring that pull doesn’t make it disappear.

Understanding it does.

This is only the beginning.

Section II — The Psychology Beneath the Attraction: Why Calm Darkness Feels Powerful

Before we talk about Hannibal, Joker, Bateman, or Johan, we have to talk about us.

Because the uncomfortable truth is this: cinema does not hypnotize us against our will. It responds to something already present. These characters do not create darkness inside the audience — they activate it.

Not in a violent way. In a psychological one.

The Shadow We Pretend Not to Have

Carl Jung spoke about the shadow as the part of the psyche we exile in order to function socially. It contains impulses that are not acceptable, not polite, not safe — anger, dominance, envy, cruelty, selfishness, desire for control.

Modern life demands constant self-regulation. We are trained early to:

- Lower our voices

- Apologize pre-emptively

- Be agreeable

- Be productive without being disruptive

The shadow does not disappear under these conditions. It goes underground.

Cinema gives it oxygen.

When Johan Liebert speaks softly while destroying lives, when Hannibal Lecter remains composed in a cage, when John Doe calmly explains his logic — the shadow recognizes itself.

Not as an instruction.

As a reflection.

And reflections are seductive because they feel true.

Why Calm Is More Terrifying — and More Attractive — Than Rage

Loud anger is familiar. We see it every day. It feels human, messy, reactive.

Calm, on the other hand, signals something else entirely.

Neurologically, calm under threat suggests:

- Control

- Predictive confidence

- Emotional insulation

A person who remains calm during chaos appears to have access to an inner order that others lack.

That illusion of inner order is magnetic.

Patrick Bateman does not lose control — he performs it.

Hannibal does not rush — he waits.

Johan does not argue — he erases.

Calm suggests mastery.

And mastery — even when morally twisted — reads as strength to the human brain.

The Seduction of Certainty in an Anxious World

We live in an age of hesitation.

Endless choices.

Endless information.

Endless moral negotiation.

Most people are exhausted by ambiguity.

So when a character appears who knows exactly who they are — even if who they are is monstrous — it feels relieving.

John Doe does not question his mission.

The Joker does not seek approval.

Ranvijay does not apologize for his rage.

They are terrible — but they are certain.

And certainty is intoxicating to a nervous system drowning in doubt.

Power Without Permission

Another reason these characters feel powerful is because they do not ask.

They do not ask for love.

They do not ask for validation.

They do not ask for forgiveness.

They take space.

In a society that rewards politeness and punishes dominance — especially emotional dominance — watching someone occupy space unapologetically can feel transgressive and liberating.

This does not mean audiences want to behave that way.

It means they want to feel what that freedom tastes like.

The Dark Triad, Stripped of the Buzzwords

Psychology often talks about narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy — the so-called Dark Triad.

But cinema removes the clinical coldness and replaces it with narrative heat.

What we see instead is:

- Confidence without self-doubt

- Manipulation without guilt

- Desire without shame

These traits are dangerous in real life.

On screen, they become exaggerated symbols — not instructions, but explorations.

Audiences are not applauding cruelty.

They are exploring what it would feel like to exist without internal brakes.

Audience Reviews Tell the Same Story

When viewers describe these characters, the language is revealing:

“He’s horrifying but composed.”

“He’s evil but intelligent.”

“He’s wrong but honest.”

Notice what people admire.

Not the violence.

The clarity.

The stillness.

The absence of confusion.

People don’t fantasize about killing.

They fantasize about not feeling weak.

The Psychological Trade-Off We All Make

To function in society, we trade raw power for safety.

We trade dominance for belonging.

We trade certainty for acceptance.

Cinema temporarily reverses that trade.

For two hours, we get to watch someone who does not compromise — and survive.

That fantasy is compelling precisely because it is unrealistic.

And safe.

Where Fascination Becomes Self-Interrogation

At some point, fascination turns inward.

The question shifts from:

“Why is he like this?”

to:

“Why am I watching this so closely?”

That moment is the beginning of maturity — not moral collapse.

Because the goal of engaging with dark characters is not imitation.

It is integration.

Understanding the shadow so it does not unconsciously control us.

In the next section, we stop speaking in abstractions and begin dissecting the characters themselves — starting with the most elegant monster of them all: Hannibal Lecter.

Because some darkness whispers instead of screams — and that is what makes it unforgettable.

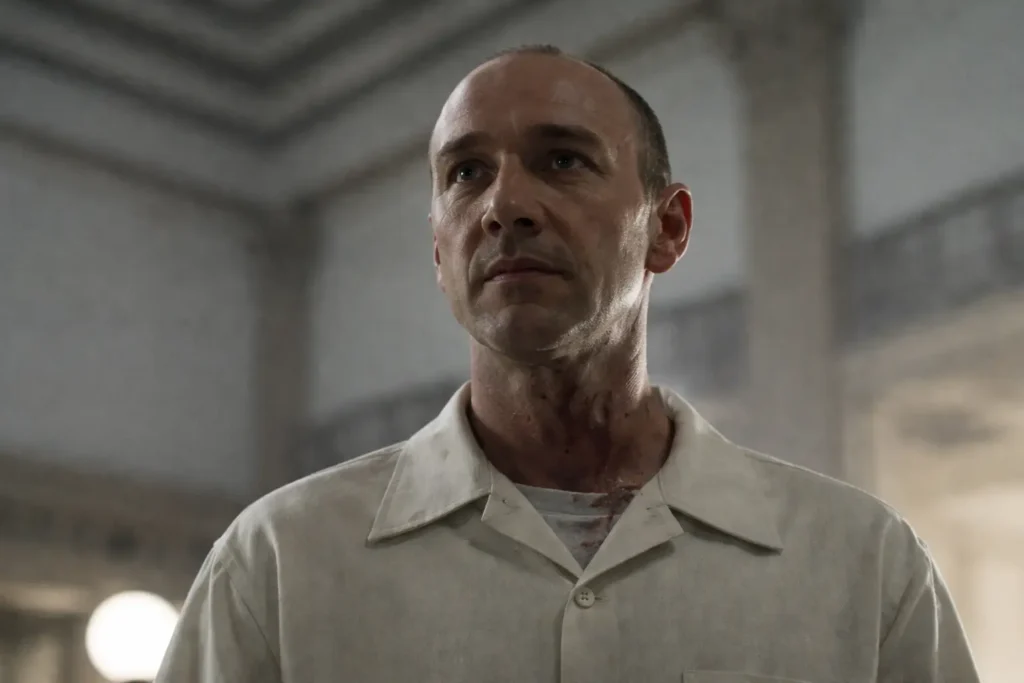

Section III — Hannibal Lecter: The Elegance of the Predator

If chaos is loud, Hannibal Lecter is silent.

That silence is not empty. It is deliberate.

When Hannibal Lecter enters a scene, the room does not explode — it tightens. People lean forward. Voices soften. Movements slow. Even authority figures recalibrate themselves around him. This is not fear in the conventional sense. It is attention.

And attention is power.

Politeness as a Weapon

Hannibal Lecter does not dominate through volume or physical intimidation. He dominates through courtesy.

“Please.” “Thank you.” “Good evening.”

These words should signal safety. Instead, they disarm.

Audiences repeatedly mention this contradiction in reviews:

“He’s terrifying because he’s polite.”

“The way he speaks makes everything worse.”

Politeness lowers defenses. It creates a false sense of normalcy. Hannibal weaponizes that instinct.

What we are witnessing is not just a psychopath — it is a predator who understands human social codes better than the humans around him.

Intelligence as Seduction

Hannibal is not just smart — he is aesthetic about intelligence.

He references art.

He appreciates music.

He speaks in metaphors.

He does not rush to prove his superiority. He assumes it.

Audience reactions often reveal admiration wrapped in discomfort:

“I hate how intelligent he is.”

“He feels untouchable.”

Intelligence, when paired with emotional detachment, reads as dominance. Hannibal is never scrambling. Never reactive. Never desperate.

He has already solved the room before anyone else arrives.

The Calm That Feels Godlike

One of the most unsettling aspects of Hannibal Lecter is his emotional economy.

He does not waste feeling.

Anger is rare.

Fear is absent.

Joy is subtle.

This emotional restraint creates the illusion of transcendence — as if he operates on a plane above ordinary human chaos.

That illusion is intoxicating to watch.

In audience discussions, people often describe Hannibal using language usually reserved for gods or kings:

“Regal.”

“Above everyone.”

“Untouchable.”

This is not accidental. Cinema frames him that way.

Why Audiences Are Drawn to Him (And Ashamed of It)

Hannibal Lecter embodies traits many people suppress:

- Control

- Precision

- Emotional restraint

- Intellectual superiority

In real life, these traits are softened for social survival.

On screen, they are sharpened.

Viewers do not want Hannibal’s violence.

They want his self-possession.

That distinction matters.

The Dangerous Fantasy of Being Unbothered

Perhaps the most seductive thing about Hannibal Lecter is not his cruelty — it is his immunity.

Nothing rattles him.

In a world where people are constantly reacting, apologizing, explaining, and justifying, Hannibal’s emotional invulnerability feels like freedom.

Audience comments often circle this idea without naming it:

“He’s always in control.”

“Nothing gets to him.”

What they are responding to is not evil.

It is unshakeability.

The Line Hannibal Forces Us to Confront

Hannibal Lecter confronts the audience with an uncomfortable truth:

Refinement does not equal morality.

Intelligence does not equal goodness.

Calm does not equal safety.

And yet — we are conditioned to associate these traits with leadership, success, and trust.

Hannibal exploits that conditioning.

That is why he stays with us.

Personal Reflection: Why Hannibal Lingers

When I think about Hannibal Lecter, I realize my fascination was never about fear.

It was about envy — not of his actions, but of his internal stillness.

The ability to sit in a room and not need anything.

No approval.

No reassurance.

No validation.

Just presence.

That is a dangerous fantasy — and an honest one.

Hannibal Lecter is not compelling because he is monstrous.

He is compelling because he reveals how easily monstrosity can wear elegance.

In the next section, we move from elegance to emptiness — from the refined predator to the hollow man behind the mask.

Next: Patrick Bateman and the Violence of Identity.

Section IV — Patrick Bateman: Masks, Masculinity, and the Horror of Being Nobody

If Hannibal Lecter feels like a god observing humans, Patrick Bateman feels like a human desperately trying to convince himself he exists.

This is why American Psycho unsettles audiences in a very different way.

Hannibal terrifies us from above.

Bateman disturbs us from within.

The Mask That Never Comes Off

Patrick Bateman is not hiding who he is.

He is the hiding.

Every aspect of his life is performance:

- The morning routine

- The business cards

- The restaurant reservations

- The suits, the music, the vocabulary

Bateman does not live — he curates.

Audience reviews often capture this eerily:

“It feels too real.”

“Everyone knows someone like this.”

“It’s exaggerated, but not by much.”

That discomfort comes from recognition.

Capitalism as a Personality

Bateman’s world rewards surfaces.

What you wear matters more than what you feel.

Where you eat matters more than what you believe.

Status replaces identity.

Bateman adapts perfectly — and emptily.

His violence is not rebellion.

It is leakage.

The result of a man with no inner life trying to feel something — anything — through extremes.

Masculinity Without Meaning

Bateman is often misread as an “alpha male.”

He is not.

He is anxious, comparative, obsessed with hierarchy, and terrified of being insignificant.

His rage ignites not from power — but from humiliation.

The business card scene is more revealing than any murder:

A slight difference in font nearly destroys him.

Audience reactions reflect this:

“That scene made me more uncomfortable than the violence.”

Because it exposes a truth:

Modern masculinity is often built on external validation.

And when validation disappears, identity collapses.

Violence as Proof of Existence

Bateman’s crimes feel unreal — almost dreamlike.

That ambiguity is intentional.

The question is not whether he killed.

The question is whether violence was the only language left to him.

In a world that sees him only as a surface, Bateman turns to the most extreme form of self-assertion.

Not because he enjoys it.

But because it confirms he is real.

Why Some Audiences Misunderstand Bateman

Online discourse often reveals a troubling split:

Some viewers see satire.

Others see aspiration.

This says more about the audience than the film.

Bateman is not powerful.

He is hollow.

Those who admire him often confuse control with confidence — and confidence with worth.

The film holds up a mirror.

Not everyone likes what they see.

Personal Reflection: Why Bateman Feels Uncomfortably Close

Bateman unsettles me more than Hannibal ever could.

Because Hannibal is exceptional.

Bateman is ordinary.

He lives in systems we recognize.

He chases metrics we’re taught to value.

He fears irrelevance — like most people do.

The horror of American Psycho is not the blood.

It’s the possibility that emptiness can look successful.

Patrick Bateman is not a monster hiding behind a mask.

He is a mask pretending to be a man.

In the next section, we move from emptiness to annihilation — from identity collapse to identity erasure.

Next: Johan Liebert and the Terror of Nothingness.

Section V — Johan Liebert: The Silence Where a Self Should Be

If Patrick Bateman is a man screaming internally for recognition, Johan Liebert is a man who has already accepted that nothing inside him exists.

And that is why he is terrifying.

Johan does not rage.

He does not posture.

He does not seek domination in the traditional sense.

He empties people.

Evil Without Desire

Most cinematic villains want something — power, revenge, chaos, recognition.

Johan wants nothing.

This absence destabilizes audiences because it removes motivation — the very thing we rely on to explain behavior.

Viewers often describe him with a specific vocabulary:

“Cold.”

“Hollow.”

“Like death walking.”

“He doesn’t feel human.”

And yet — he looks perfectly human.

The Soft Voice That Ends Worlds

Johan’s greatest weapon is not violence.

It is persuasion.

He speaks softly, carefully, almost kindly. He does not threaten — he suggests.

And people destroy themselves.

This form of power is deeply unsettling because it bypasses force. It implies that human beings are already fragile — that all it takes is the right sentence at the right time.

Audiences don’t just fear Johan.

They fear themselves in his presence.

Why Nothingness Is Scarier Than Chaos

Chaos still has energy.

Rage still has heat.

Johan has neither.

He represents annihilation — not of the body, but of meaning.

To encounter Johan is to confront the idea that:

- Identity is fragile

- Morality is optional

- Existence itself can feel empty

This is why many viewers report feeling disturbed long after watching Monster.

There is no catharsis.

Only absence.

Audience Reactions: The Lingering Effect

Unlike Joker or Bateman, Johan rarely inspires quotes or memes.

Instead, audience reactions are quieter:

“He stayed with me for weeks.”

“I couldn’t stop thinking about him.”

“He made me feel uneasy in a way I couldn’t explain.”

This is the mark of existential horror.

Not shock.

Aftermath.

Personal Reflection: Why Johan Is the Most Honest Villain

Johan frightens me not because he is powerful — but because he feels true.

In moments of depression, alienation, or burnout, many people glimpse that same void.

Johan simply never looks away.

He does not dramatize emptiness.

He accepts it.

And that acceptance is unbearable to watch.

Johan Liebert is not chaos.

He is the silence after meaning collapses.

In the next section, we move from emptiness to rebellion — from annihilation to laughter in the face of order.

Next: The Joker and the Seduction of Chaos.

VI. The Joker — Chaos as Truth, Laughter as Rebellion

There is a reason the Joker refuses to stay dead. Every generation resurrects him in a new costume, a new laugh, a new philosophy. He adapts because he is not a character — he is a response. To order. To hypocrisy. To the suffocating pressure of pretending that things make sense when they don’t.

When Heath Ledger’s Joker asks, “Why so serious?”, it isn’t a joke. It’s an accusation. Directed at Batman, yes — but also at the audience. At a society obsessed with rules that benefit the powerful while punishing the fragile. Ledger’s Joker is not chaos for fun. He is chaos as exposure. He burns money not because he doesn’t value it, but because he wants to show how desperately others do.

Audiences responded viscerally. Reviews often describe him as “terrifying but honest,” “evil yet logical,” “mad but right.” That last word — right — is dangerous. It reveals something uncomfortable: people don’t just fear the Joker; they feel seen by him.

Joaquin Phoenix’s Joker pushes this further inward. This is not a criminal mastermind but a social casualty. A man laughed at until he learns to weaponize laughter itself. The audience reaction here split sharply. Some saw a cautionary tale about neglect and mental illness. Others — disturbingly — saw a hero’s journey. The reviews tell the story: “I finally felt understood,” “This is what society creates,” “He snapped — and I don’t blame him.”

This is where fascination becomes identification.

The Joker appeals most strongly to audiences who feel unheard, humiliated, or invisible. Chaos becomes attractive when structure has failed you. Violence feels philosophical when it is framed as rebellion. The Joker doesn’t promise control like Hannibal or status like Bateman. He promises release.

But here’s the uncomfortable truth I keep circling back to as a viewer: the Joker is not freedom. He is surrender disguised as honesty. Chaos doesn’t liberate — it erases. And yet, in a world where many feel erased already, that promise feels intoxicating.

The Joker laughs because he has nothing left to lose. And audiences, exhausted by pretending they do, laugh with him.

VII. John Doe (Se7en) — Moral Absolutism and the Seduction of Certainty

John Doe is terrifying not because he is loud, charismatic, or physically imposing. He is terrifying because he is calm. He arrives already convinced. He does not seek attention; attention follows him like an afterthought. In a cinematic universe crowded with flamboyant villains, John Doe stands out by doing almost nothing theatrically — and that restraint is exactly why audiences remember him.

What unsettles viewers is not merely the violence of his acts but the coherence of his belief system. He has a thesis. He has footnotes. He has a conclusion. And worst of all, he never wavers. In a world where most people doubt themselves daily, certainty feels powerful.

Audience reviews often reveal an uncomfortable admiration: “He was wrong, but he wasn’t stupid,” “He had a point,” “He committed to his philosophy.” That last sentence appears again and again. Commitment itself becomes the virtue. Not compassion. Not restraint. Commitment.

John Doe embodies moral absolutism — the belief that the world is so corrupt that extreme measures are not just justified, but required. This mindset is seductive because it simplifies chaos. There is good. There is evil. There is punishment. There is meaning. No ambiguity. No nuance. No exhausting gray zones.

And audiences are tired of gray.

Watching Se7en, I remember feeling a strange chill during the final act — not just because of what happens, but because the film dares to suggest that John Doe wins. Not tactically, but philosophically. He bends the moral universe until it aligns with his design. The detectives react; he orchestrates. The system responds; he defines.

That imbalance resonates with viewers who feel powerless in their own lives. John Doe offers a fantasy where outrage is purified into action. Where disgust becomes destiny. Where the world’s ugliness finally means something.

But moral absolutism is not clarity — it is a refusal to see complexity. John Doe’s certainty requires dehumanization. Sinners become symbols. People become lessons. Once that shift occurs, violence feels educational rather than cruel.

The audience’s fascination here reveals a dangerous psychological craving: not for chaos like the Joker, but for order enforced without doubt. In uncertain times, the most frightening villains are not the ones who laugh — but the ones who never question themselves.

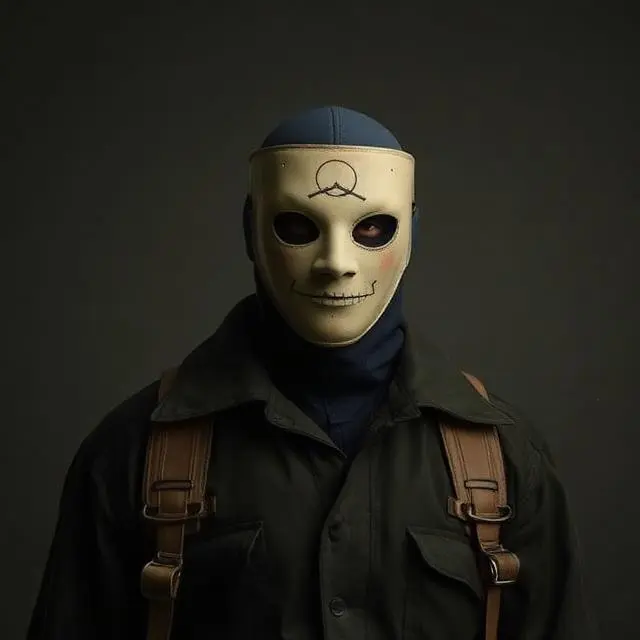

VIII. Zodiac — Obsession, Mystery, and the Power of the Unfinished

The Zodiac Killer does something most cinematic villains never do: he withholds himself. No monologues. No confession. No final unveiling. He exists primarily as absence — a trail of symbols, letters, dead ends, and unanswered questions. And somehow, that makes him immortal.

Audiences often describe Zodiac not as frightening, but as unsettling. Reviews say things like: “It stayed with me,” “I kept thinking about it for days,” “There was no closure and that was the worst part.” This reaction reveals something crucial about audience psychology — humans are far more disturbed by ambiguity than by brutality.

Unlike John Doe, Zodiac offers no moral framework. Unlike Joker, no emotional catharsis. Unlike Hannibal, no elegance. What he offers instead is a vacuum — and the human mind rushes to fill it.

The film turns obsession itself into the antagonist. Detectives, journalists, civilians — even the audience — become trapped in the same loop: pattern-seeking, meaning-making, hoping that one more clue will bring resolution. Zodiac becomes powerful not because of what he does, but because of what he refuses to give.

Psychologically, this taps into the Zeigarnik effect — our tendency to remember unfinished tasks more vividly than completed ones. An unsolved killer lingers longer than a caught one. Mystery invites projection. Silence invites mythology. The less we know, the more intelligent, calculated, and omnipotent we imagine him to be.

Watching Zodiac, I realized how complicit the audience becomes. We lean forward. We connect dots that may not exist. We want him to be brilliant because randomness feels unbearable. Meaningless violence is harder to accept than designed cruelty.

Zodiac represents a modern fear: that the universe is not narratively satisfying. That evil may never explain itself. That effort does not guarantee resolution. In a media landscape trained to expect answers, Zodiac feels like an insult — and that insult is precisely why audiences cannot let him go.

The fascination here is not admiration. It is captivity. Zodiac doesn’t seduce the audience; he traps them. And once trapped, the mind keeps returning, hoping this time the story will finally close.

IX. Ranvijay (Animal) — Masculinity, Rage, and the Indian Audience Split

Ranvijay is not subtle. He doesn’t need to be. His power lies in excess — excess love, excess violence, excess devotion, excess entitlement. Watching Animal felt less like watching a character arc and more like watching a cultural wound tear itself open on screen.

Indian audience reactions were not merely divided; they were polarized. Reviews read like ideological battle lines. “He’s toxic but honest,” “Finally a real man on screen,” sit right beside “This glorifies abuse,” and “This is dangerous masculinity.” The heat of the reaction tells us something important: Ranvijay is not just a character — he is a mirror.

At his core, Ranvijay is built around a single emotional axis: father-worship. His violence is not random; it is devotional. Every act of brutality is framed as loyalty, protection, proof. The film repeatedly confuses love with possession, concern with control. And many viewers — disturbingly — accept this equation without resistance.

Psychologically, Ranvijay appeals to audiences who feel emasculated by modern ambiguity. In a society negotiating changing gender roles, economic anxiety, and emotional repression, his certainty feels grounding. He does not hesitate. He does not ask permission. He does not apologize. For some viewers, that alone reads as strength.

But strength without self-reflection becomes tyranny. Ranvijay’s world is binary: mine or enemy, loyal or disposable. Women exist primarily as extensions of his emotional needs — to be protected, possessed, or punished for disobedience. Critics called this misogyny; fans called it realism. That argument itself exposes a deeper cultural conflict: whether cinema should reflect existing violence or interrogate it.

What unsettled me most while reading audience reactions was how often morality was replaced with vibe. Viewers admitted the character was wrong — but insisted he felt “raw,” “authentic,” “unfiltered.” In other words, emotional intensity became a substitute for ethical responsibility.

Ranvijay is the alpha-male fantasy stripped of elegance. No Hannibal-like refinement. No Bateman satire. Just rage validated by narrative framing and cinematic grandeur. And when violence is shot beautifully, audiences struggle to see it as critique.

The fascination here is not with evil — it is with permission. Permission to be angry. Permission to dominate. Permission to stop explaining oneself. Animal doesn’t create this desire; it reveals it. And the audience reaction proves how badly some people want that permission to exist.

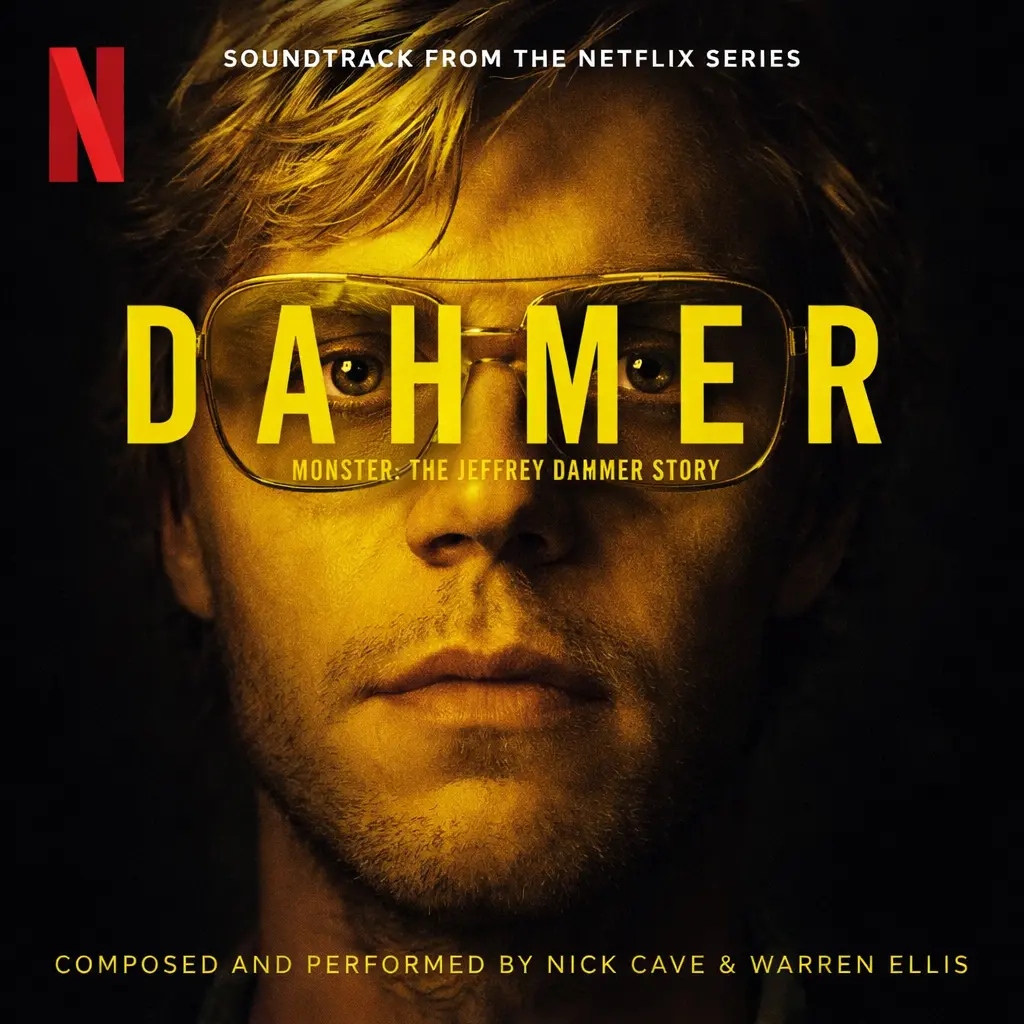

X. Dahmer & Raman Raghav — When the Camera Refuses to Look Away

Dahmer

There is a particular kind of discomfort that comes from watching Jeffrey Dahmer or Raman Raghav. Unlike Hannibal or Joker, these figures offer no fantasy of power, no seductive philosophy, no aesthetic pleasure. There is nothing aspirational here. And yet — people watch. In massive numbers.

Audience reviews for Dahmer are filled with conflicted language: “I felt sick,” “I didn’t enjoy it but couldn’t stop,” “I don’t know why I watched the whole thing.” Raman Raghav receives similar reactions in Indian contexts: “Brilliant but disturbing,” “Hard to sit through,” “Nawaz was terrifyingly real.”

This is not admiration. It is compulsion.

Psychologically, these portrayals activate voyeurism mixed with a desire for comprehension. Viewers are not asking, “What would it be like to be him?” They are asking, “How does someone become this?” The horror lies not in theatrical evil, but in banality — apartments, routines, loneliness, addiction, neglect.

Dahmer is framed as painfully ordinary. Socially awkward. Isolated. Broken long before he is monstrous. This framing creates ethical tension. Some viewers accuse the series of humanizing him too much; others argue that understanding is not the same as excusing. The discomfort arises because the line between explanation and sympathy feels dangerously thin.

Raman Raghav, by contrast, is feral, almost mythic — a creature born of neglect, poverty, addiction, and spiritual delusion. He speaks in riddles, laughs at suffering, drifts between reality and hallucination. Indian audiences often interpret him as a product of systemic failure rather than individual pathology. But that framing, too, risks abstraction — turning victims into footnotes.

What both characters expose is the audience’s uneasy relationship with suffering. We want to look away — but we don’t. Because if we can trace the origin of monstrosity, maybe we can convince ourselves it won’t happen again. Maybe we can keep it contained.

Personally, these were the hardest portrayals to sit with. There is no catharsis, no moral victory, no intellectual distance. The camera lingers. And by lingering, it implicates us. Watching becomes participation. Not in the violence — but in the refusal to look away from it.

These stories ask a brutal question: if evil is not glamorous, not intelligent, not charismatic — just broken and banal — what does that say about the world that produced it?

XI. Willy Wonka — Whimsy, Control, and the Tyranny of Charm

Willy Wonka is not a villain in the traditional sense. He does not kill to satisfy lust, rage, or ideology. Yet, revisiting Charlie and the Chocolate Factory as an adult reveals a quiet, insidious form of control hidden beneath whimsy. Wonka orchestrates every detail, from the Oompa-Loompas’ choreography to the tests each child faces. The factory is a stage, and he is the director — omniscient, playful, and always observing.

Audiences often underestimate his influence. Children see fun, magic, and wonder. Adults see moral lessons. But beneath both perspectives lies authoritarian precision. Each child’s failure is met with poetic justice. Each success is rewarded — but never without scrutiny. Reviews often note this duality: “Magical but eerie,” “I forgot how creepy he really is,” “Adult Wonka is a master manipulator.”

What fascinates the audience is not the threat of physical harm. It is the management of fate. Wonka’s charm masks his absolute control over others’ destinies. It’s a subtle reminder that charisma itself can be a weapon — a way to bend people’s choices without explicit coercion. In psychological terms, he models a different kind of power: indirect, playful, yet entirely encompassing.

Watching Wonka reminds us why audiences are drawn to figures who are both enigmatic and omnipotent. It’s not evil that seduces here — it is mastery disguised as delight. His charm allows transgression — but on his terms. That tension, between freedom and orchestration, is what leaves viewers both enchanted and uneasy.

Personally, I’ve realized revisiting Wonka as an adult felt eerily like staring at Hannibal through a whimsical lens. The lesson: charisma + control = enduring fascination, whether cloaked in blood or chocolate.

This subtle seduction sets the stage for the final psychological analysis, where we tie together why these men — from Hannibal to Wonka — captivate audiences despite moral repulsion.

XII. The Psychology of the Audience — Why We Watch, Why We Return

Having journeyed through Hannibal, Bateman, Johan, Joker, John Doe, Zodiac, Ranvijay, Dahmer, Raman Raghav, and even Willy Wonka, the question looms: why do we keep coming back? Why do these men — real or imagined — captivate us, disturb us, and linger long after the credits roll?

The Shadow We Crave

Jung’s shadow theory reappears here, but now in the audience’s mind. We are drawn to what we suppress: our rage, our desire for control, our unexpressed ambition, our forbidden thoughts. These characters act out what society forbids us to. By watching, we experience our shadow without consequence.

Safety Through Distance

We admire these men precisely because they operate in a space we cannot occupy safely. Hannibal’s manipulation, Joker’s chaos, Ranvijay’s rage — thrilling from afar, perilous up close. The distance allows fascination without risk. We can explore the darkness of human nature while remaining ethically intact.

The Allure of Competence

Across these characters, a recurring trait emerges: competence. Control, intelligence, skill, decisiveness — qualities we often admire, even in evil. Audiences are drawn to mastery more than morality. Reviews frequently echo this: “I hate him but I can’t deny his brilliance,” “Terrifying yet impeccable in execution.”

Identification and Reflection

Some characters invite identification: Bateman’s performance anxiety, Joker’s social alienation, John Doe’s ideological certainty. In these cases, fascination is partly narcissistic: seeing ourselves in exaggerated form, exploring extremes we do not dare enact.

Catharsis and Emotional Release

Others provide emotional release: the thrill of transgression, the satisfaction of watching a system challenged or a narrative inverted. Chaos and rebellion are emotionally cathartic, especially when framed within a story that contains them safely.

The Danger and Ethics of Fascination

Not all fascination is benign. Admiration for Ranvijay’s masculinity, or empathy for Dahmer and Raghav, reveals ethical tension. We are aware, consciously or unconsciously, that consuming violence and charisma can blur moral boundaries. Audience reviews reflect this tension: “I know this is wrong but I can’t stop watching.” The conflict between curiosity and ethics intensifies engagement.

The Personal Pull

On a personal note, I recognize the seductive effect these characters have on me. They reveal uncomfortable truths: about control, fear, desire, and the fantasies we suppress. Watching them is a mirror — sometimes flattering, sometimes horrifying, always reflective. This blend of attraction and repulsion is the engine of cinematic engagement.

In essence, we watch because we are human: curious, reflective, and drawn to extremes that illuminate the spectrum of our own nature.

XIII. Why We Keep Returning to These Men — Reflection and Synthesis

After tracing the arcs of Hannibal, Bateman, Johan, Joker, John Doe, Zodiac, Ranvijay, Dahmer, Raman Raghav, and Wonka, a pattern emerges. Each embodies a different form of power, absence, or transgression. And yet, we return to them — sometimes obsessively, sometimes reluctantly — because they reflect parts of ourselves we cannot safely explore.

Attraction to Extremes

We are drawn to extremes because they illuminate mediocrity. Hannibal’s control makes our indecision palpable. Bateman’s hollowness mirrors our performative selves. Johan’s void reminds us of our own existential fragility. Joker’s chaos tempts us to abandon constraint. John Doe’s certainty mocks our hesitation. Zodiac’s mystery challenges our need for closure. Ranvijay’s rage forces confrontation with cultural and emotional expectations. Dahmer and Raghav show us that banality can harbor unspeakable darkness. Wonka reminds us that charm can mask domination.

Cinematic Safety and Ethical Distance

We can explore these traits safely on screen. Cinema provides a buffer: we watch, analyze, and return to our lives unscathed. That distance allows fascination to thrive without consequence, a rare gift in real life.

The Personal Reflection

For me, returning to these characters is a mirror into my own curiosity, fears, and suppressed desires. They force uncomfortable self-inquiry: what do I admire? What repels me? Where do I see myself? The process is both humbling and exhilarating.

The Enduring Seduction

The truth is uncomfortable: we return to these men because they embody qualities we recognize, suppress, or long for. Control, charisma, certainty, chaos, rebellion, and mastery are universal magnets — and these characters wear them in extremes that make their worlds impossible and fascinating.

We are not drawn to evil for its own sake. We are drawn to reflection, projection, and confrontation. We are drawn to what the world has conditioned us to hide.

And in that mirror, we see ourselves — frightened, fascinated, and strangely alive.

This concludes the exploration of why cinema’s most captivating men continue to haunt audiences, inviting us to engage with the shadow, the void, and the extremes of human nature.

Why Quentin Tarrantino feels different…